Batho Bonke Capital has sold its shares in Absa.

In the south of the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the Congo River rises from the Katanga Plateau to arc across central Africa and drain into the Atlantic, lies one of the world’s richest mineral stores.

Katanga Province is best known for its copper and cobalt mines, but its mosaic of ailing farms, degraded woodlands and dire poverty also belies a wealth of uranium, manganese, diamond and tin deposits.

For decades, this “veritable geological scandal”, as an early European surveyor memorably described the profusion, has fuelled repeated cycles of secessionist violence. Last year rebel groups pushing for Katanga’s independence attacked its capital, Lubumbashi. The fighting has displaced thousands of people.

But the promise of riches has also attracted a procession of mining companies, investors and financiers searching for high-return investments.

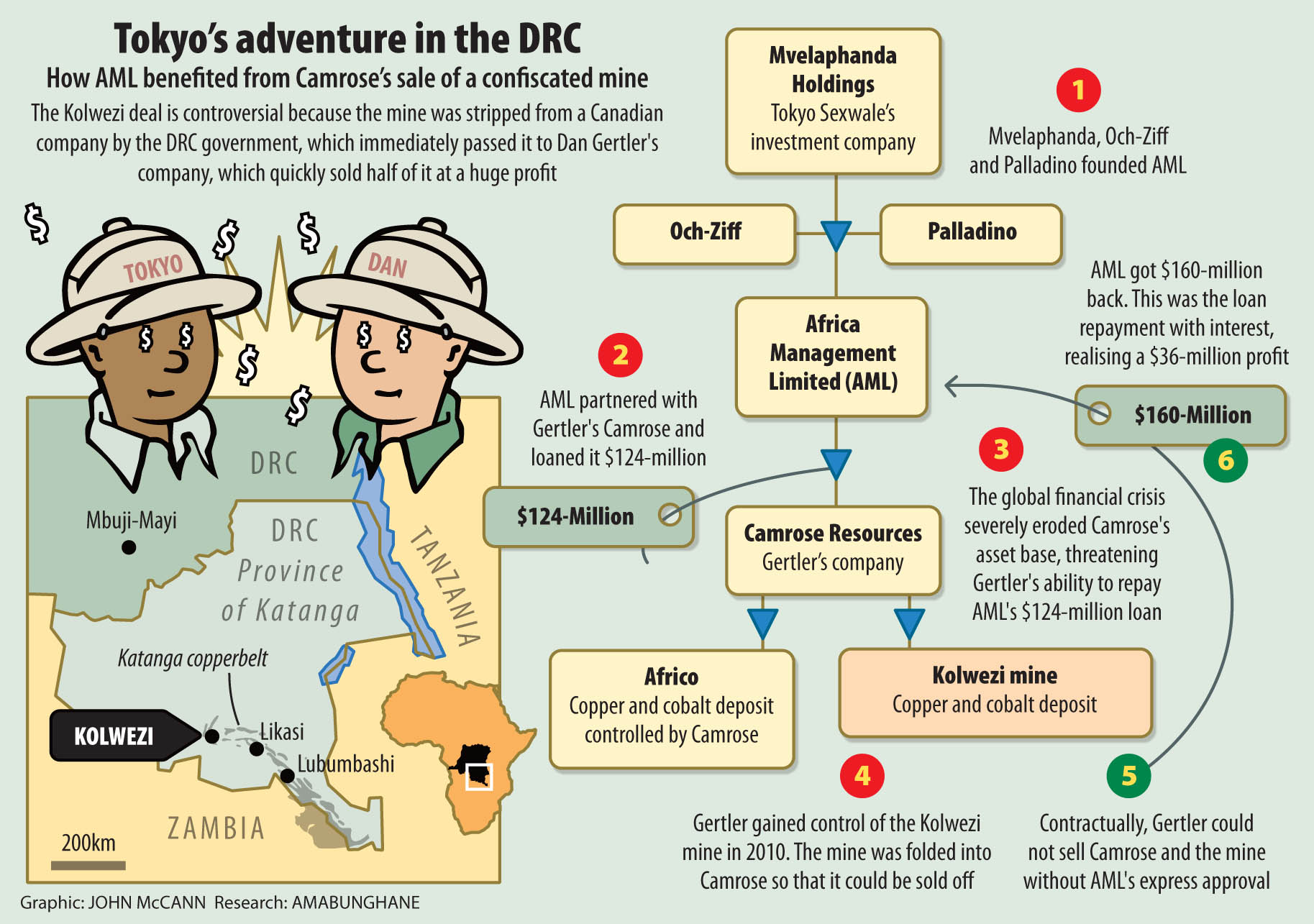

Among Katanga’s most recent fortune-hunters was Africa Management Limited (AML), a company founded in 2008 by anti-apartheid struggle hero Tokyo Sexwale, South African businesspeople Mark Willcox and Walter Hennig and the $40-billion United States hedge fund, Och-Ziff Capital Management.

Willcox, Sexwale’s right-hand man since they formed Mvelaphanda Holdings in 1998, is particularly close to Hennig, a shadowy character from the Western Cape farming town of Piketberg. Hennig was previously embroiled in controversy after his company loaned $25-million to the West African nation of Guinea in 2011. Guinea in return promised the company astonishing minerals rights.

Wilcox: Sexwale’s right-hand man

Wilcox: Sexwale’s right-hand man

Walter Hennig, controversial Western Cape businessman

Och-Ziff featured in an earlier amaBhungane investigation, which uncovered how the hedge fund was the source of a $100-million loan that allowed President Robert Mugabe to crush a potential opposition victory in the 2008 Zimbabwean election.

Launched in the same month as Och-Ziff’s Zimbabwe deal, AML’s unrelated Katanga foray was a toe-curling financial adventure that nearly ended in disaster after the 2008 financial crisis punched a hole in their R1-billion investment. But they were rescued – and even turned a healthy profit – when their partner, Dan Gertler, a controversial friend of DRC President Joseph Kabila, executed a now infamous takeover of a valuable copper mine outside a Katanga mining town.

That rescue deal could yet prove a headache for Sexwale. AML looks set to be drawn into a corruption investigation by US authorities, who are scrutinising a number of Och-Ziff’s African investments.

Och-Ziff disclosed in March that it was under investigation but was vague about the details. Neither it nor the authorities have confirmed that the investigation includes the DRC deals with Gertler.

But, in April this year, the Wall Street Journal linked the investigation to the Gertler investments, prompting a crash in the company’s share price. Pressed by an analyst, Och-Ziff did not deny the Gertler connection.

The United Kingdom’s Independent newspaper reported last month that a former Och-Ziff executive, who was central to its partnership in AML, has hired lawyers to represent him in the investigation.

Hennig, Willcox and Gertler said they had not been contacted by US authorities. Sexwale and Och-Ziff did not respond to questions.

The Mail & Guardian has previously reported that AML lent about R1-billion to Gertler, a controversial Israeli billionaire, to buy into a Katanga mine six years ago.

AML denies that this investment made it a party to Gertler’s increasingly audacious later deals, including the “grab” of the Kolwezi copper project, which he flipped (sold on) to a multinational company at a large profit. But amaBhungane’s latest investigations show that a dedicated partnership existed between AML and Gertler, and not just a loan. Not only did AML profit from Kolwezi but Gertler also needed its express consent before he could sell the mine, suggesting that AML was much more than a blind, powerless lender.

The gatekeeper

Who is Gertler? In 2012, Foreign Policy magazine described the DRC as “the poster child of the resource-cursed failed state” – doing deals there “is all but impossible without a well-connected political patron”. And Gertler was “perhaps the most wired of them all”.

The descendent of a long line of influential Israeli diamond traders, Gertler arrived in the DRC at the turn of the century, then in his early 20s.

He soon befriended then-president Laurent Kabila and bagged a lucrative state diamond deal.

After Kabila was succeeded by his son Joseph, Gertler remained a family friend. In particular, he was close to Joseph’s adviser, Augustin Katumba Mwanke.

A 2009 US diplomatic cable published by Wikileaks described Katumba as “a kind of shady, even nefarious figure within Kabila’s inner circle … He is believed to manage much of Kabila’s personal fortune. He is known to be close to Gertler.”

The cable continued: “Gertler, according to some sources, lends Kabila his private jet for trips abroad. Gertler has invited Katumba to Israel often.”

When Katumba was killed in a plane crash early in 2012, Gertler attended the funeral. Kabila aide Antoine Ghonda told the London Sunday Times in 2011: “Dan Gertler is a friend. The way our president works, he has close contacts and protects them.”

A 2013 report by the Africa Progress Panel, an advocacy group chaired by former United Nations secretary general Kofi Annan, alleged that undervalued mine sales by the Kabila government to Gertler had cost the DRC about $1.4-billion.

Gertler has been described as the gatekeeper foreign investors must accommodate if they want to benefit from the DRC’s vast mineral wealth.

Speaking through a London public relations firm, Gertler strenuously denied the allegations, and insisted that his critics have produced no evidence of corruption. He disputed the panel’s claims that he has plundered the DRC, and said that his projects have attracted billions in foreign investment, creating jobs and catalysing infrastructure development.

Scramble for the DRC

Gertler’s connection with Sexwale was established through AML, which was launched in January 2008 by Sexwale’s Mvelaphanda Holdings, Och-Ziff and Hennig’s Palladino Holdings. Its purpose was to hunt down African mineral deals.

Mvela would provide assets and “political expertise on the continent” and Och-Ziff brought the “financial clout”, said Willcox, who was then chief executive of both AML and Mvela, which he and Sexwale co-founded.

Responding to amaBhungane’s questions, Mvela sought to distance itself from AML, saying it never took up shares. But it admitted to remaining an active participant in the company’s deal-making activity (See “Mvelaphanda’s role”).

Willcox told the Sunday Times at the time of the launch: “There’s a race for assets in Africa … We have already been successful in procuring substantial uranium, coal, iron ore, copper and cobalt assets on the continent.”

In another interview, he said: “We have R1.5-billion in the DRC, where we are looking at copper-cobalt consolidation. In the past six months, we have never seen as many opportunities.”

Company documents seen by amaBhungane show how one of AML’s first moves was to partner Gertler in mid-2008. AML lent his company, Camrose Resources, $124-million (about R1-billion then).

The main purpose of the loan was to fund the acquisition of a significant stake in a Katanga copper-cobalt mine through a Canadian-listed miner, Africo Resources.

Mashitu copper mine, operated by the Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation, which came to the rescue of AML. (Bloomberg)

But the documents also indicate that this was more than just a money-lending exercise.

The intention was for Gertler’s Camrose to pursue AML’s DRC copper and cobalt consolidation. AML saw Camrose as its “platform” for further investments in the DRC, and Gertler’s broader group of companies – a complex web of offshore entities that included Camrose – was expected to treat AML as a priority partner in any future mine acquisitions.

AML was also entitled to a Camrose board observer’s seat and significant controls, including veto rights, over the company.

If things went as planned, AML would convert its loan into an ownership stake in Camrose. The arrangement gave the South Africans and Och-Ziff a foothold in Katanga, while protecting them from big losses.

It was a plan that went badly awry.

Instability and risk

Later that year the financial crisis wreaked havoc in global markets, driving down Africo’s share price, thereby severely eroding AML’s loan collateral.

“The world collapsed and Africo’s share price dropped. Dan [Gertler] was in a terrible state,” said a person close to the transaction.

As a loan condition, Gertler was obliged to make sure there was always enough security – understood to be at least $165-million – to protect AML. But at the end of 2008, Camrose’s shares in Africo were worth a piffling $25-million.

AML denies the investment had gone under, saying that Camrose’s assets “at all times provided more than adequate security”. It mentioned Camrose’s stake “of significant value” in a copper concession called Kansuki.

The claim is highly dubious. AML’s own 2008 figures showed that Kansuki needed considerable investment over at least two years before its value could be unlocked and, in any event, it would have been tough to sell in the crisis years of 2008 and 2009.

Gertler’s spokesperson Peter Ogden gives a more realistic picture of that period: “The [DRC] could not attract other foreign investors, [who were] unwilling to expose themselves to such instability and risk.”

AML also marked Africo’s cash as a source of security. But the latter’s minority shareholders would have been unlikely to allow nearly two-thirds of its limited reserves to be siphoned from the balance sheet, risking an already troubled enterprise, to rescue Gertler and AML.

If Gertler could not top up the security in some other way, AML appeared to face a devastating financial loss.

Rich dump

A solution lay in the mining centre of Kolwezi, which was established in the 1930s by a Belgian mining company seeking to exploit Katanga’s mineral wealth and cheap labour. The DRC’s fourth largest town, it straddles the richest part of the Katanga copperbelt.

It boasts a small airport, a railway, a power supply and, most importantly, two dumps holding millions of tonnes of copper and cobalt that can be extracted using modern techniques.

The dumps fall under the DRC’s mining permit 652, also known as the Kolwezi tailings project.

It was Gertler’s controversial acquisition and sale of a stake in this permit, in 2010, that ultimately saved Sexwale, Willcox, Hennig and Och-Ziff’s sinking investment.

Publicly available company and court records show how the rescue came together in stages.

First, the owner of the mine was dispossessed by the DRC government; then the permit was immediately transferred to a group of companies owned by Gertler; and finally, Gertler’s group sold half of its stake in the mine to a multinational mining house, thereby guaranteeing AML’s profit.

The shakedown

The company that held the permit in 2009 was Toronto-listed First Quantum Minerals, which had a partnership with the state-owned DRC mining company Gécamines.

First Quantum has said that it spent $430-million preparing the project for production, which it expected to start in 2010, employing hundreds of locals in an impoverished locality.

In September 2009, the axe suddenly fell: the company was visited by government officials and armed policemen who sealed off both the mine and its offices in Lubumbashi.

The following month, a local court held that First Quantum’s DRC subsidiary was “fraudulently” created and did not exist. The following January its mining contract was revoked.

On the same day, the government transferred the Kolwezi stake to a group of Gertler-owned companies, which paid the government a $60-million consideration.

Transparency campaigner Global Witness has cited numerous independent valuations of Kolwezi and concluded that $60-million was far below its true value. It said the deal “raises an immediate question over whether the sale of Kolwezi was designed to enrich private interests rather than to benefit the Congolese state”.

A July 2010 financial analysis by Numis Securities reached a similar conclusion: “We believe that [First Quantum] has been the victim of a classic shakedown, simply because it refused to play the ‘brown envelope [bribery] game’.”

Even the Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation (ENRC), which bought the Kolwezi stake from Gertler later the same year, became suspicious. In a report filed with the UK’s Serious Organised Crime Agency, it said: “There is a risk that the assets of [Gertler’s] group may have been obtained by corruption … and/or may result in corrupt payments being made to public officials.”

Gertler has consistently denied that officials were bribed, insisting that his companies paid a fair price for the mine: “[Gertler’s group of companies] vigorously contestsany and all accusations of wrongdoing in any of its dealings in the DRC.”

First Quantum challenged its dispossession in various international courts. But, in January 2012, it announced that it had “settled all current legal matters” with ENRC for a consideration of $1.25-billion.

Payback

AML has tried to distance itself from the Kolwezi deal, saying it ended its involvement with Gertler on the day the deal was closed. But all the evidence is that it benefited handsomely from the transaction and that it must have signed off on the sale to ENRC.

By mid-2010, it must have been desperate about ever recovering its R1-billion loan to Gertler’s Camrose. The collateral for the loan appeared to be worth nowhere near the required security of about $165-million. Camrose no longer owned Kansuki, the mine said to be “of significant value”, the Africo shares were only worth about $40-million, and Camrose’s other mines were worth very little.

Gertler’s masterstroke was to wrap Kolwezi into Camrose and offer the intended purchaser, ENRC, a controlling stake in the company for a total of $175-million.

In return, ENRC would “irrevocably” guarantee the full repayment of AML’s loan, plus interest. At the same time, AML would “irrevocably release in full” its security over Camrose and its assets, and Gertler’s group would deliver evidence of this to the new owner.

In short, Gertler’s group could not complete its onward sale of Kolwezi without AML’s express consent.

When the deal was closed on August 20 2010, everything happened at once: Kolwezi was moved into Camrose, 50.5% of Camrose was delivered to ENRC, and AML stepped out of its partnership with Gertler, its repayment now guaranteed by a multinational corporation.

Two years later, ENRC paid out the $160-million that was owed and AML’s ailing investment was transformed into what it called a “modest” $36-million profit – R300-million at the time.

AML still insists that it was not in a position to influence the Kolwezi deal, saying: “[AML] chose not to participate in the [Kolwezi] transaction and requested the loan be repaid early. We do not believe it is possible to maintain that Africa Management was a commercial beneficiary from the disputed transactions.”

But however one slices it, Sexwale’s company was spared enormous damage by a widely condemned deal that the US regulatory authorities now appear to be looking into.

Mvelaphanda’s role

Faced with questions over Africa Management Limited’s (AML’s) partnership with Dan Gertler, Mvelaphanda Holdings told amaBhungane it never took up its shareholding in the venture.

But this version, plus AML’s advertising after its 2008 launch, raised problematic questions:

- Why was Mvela’s representative, Mark Willcox, on AML’s investment committee and involved in managing various African mineral deals, and why did he remain its chief executive until 2012?

- How did it explain a 2010 disclosure to investors by the London-listed oil and gas explorer Ophir Energy that “Mvelaphanda [holds] an interest” in AML’s fund, African Global Capital? There were numerous similar, but less overt, disclosures by other listed companies.

- Why, in 2011, did Mvela transfer a $74-million stake in Ophir to African Global Capital? Was this an arms-length, market-related transaction, or was it part of Mvela’s contribution to the fund?

- Why, when Coal of Africa announced a black economic empowerment (BEE) deal with African Global Capital in 2008, did the empowerment credentials appear to rest on Mvela’s involvement?

Responding to other detailed questions, AML admitted that Mvela had “remained an associate” and that the latter “had an exclusive arrangement to introduce [the fund] to new transactions and to operate as [its] BEE partner”.

It said Mvela had “sold” the Ophir shares to African Global Capital, but it would not disclose the amount.

* Got a tip-off for us about this story? Click here.

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism (amaBhungane) produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for our stories, activities and funding sources.