Trevor Manuel is expected to give evidence relating to Fikile Mbalulas 2010 appointment as sports minister, which Manuel has publicly suggested the controversial Gupta brothers had influence over. (Paul Botes/M&G)

This week former finance minister and current Minister in the Presidency Trevor Manuel reminded South Africans of the burden of responsibility Nelson Mandela has left us.

"It's a burden of inclusiveness, it's a burden of democracy, it's a burden that will ensure that we raise the standard of living of every person," Manuel told a crowd gathered on a balmy Sunday evening outside Cape Town's City Hall to honour the death of Madiba.

"Mandela, when he said a better life for all, spoke against inequality, spoke against leaving people behind."

It cannot be said that South Africa is a country where no one is being "left behind". But it is also not the same country Mandela inherited when he became its first democratically elected president.

Yes, unemployment is high — the most recent data from Statistics South Africa puts it at 24.7% for the third quarter of 2013.

It is even higher if you consider the expanded definition of unemployment, which includes discouraged work seekers, at 35.6%.

Unemployment rate

The official unemployment rate in 1994 was about 20% and the expanded rate 31.5%, according to the 2012 South African Survey, released by the South African Institute for Race Relations.

But the rapidly changing demographics of the country do have an impact on these numbers. In his book The Long View, analyst JP Landman illustrates the point.

Thanks to a growing population, South Africa's employment figures keep rising, but so do its unemployment figures.

According to Landman's research, in 1995, there were 9.5-million people working and the percentage of working-age people employed was 39%.

By 2012, this figure had grown to 13.5-million people and the percentage of the employed working-age population had grown to 40.5%. (It was even higher at 45% in 2008 before the financial crisis.)

In contrast, the number of unemployed in 1995 was 1.9-million, with an unemployment rate of 17.7%, and in 2012 this had grown to 4.5-million and 25.7% respectively.

SA more urbanised

On top of population growth, South Africa has become more urbanised and many more women have entered the labour market, Landman says.

It is the "irony of our efforts to create employment", according to Landman.

"The more successful we are, the more people will look for jobs. Because they will not find them, they then get counted as unemployed."

Despite many challenges and a global recession, the economy continues to grow. Information supplied by ETM Analytics shows that the country's real gross domestic product (GDP), the broadest measure of economic growth, more than doubled since 1994 to reach R2.1-trillion in the third quarter of this year.

Although modest when compared with the growth of other emerging economies, GDP growth has averaged 3.2% each year since 1994.

Consumer price inflation has steadily declined from just below 9% in 1994 to 5.8% in 2013, within the country's inflation target range of between 3% and 6%.

Latest inflation numbers

The latest inflation numbers for November released on Wednesday came in at 5.3%.

Government spending has grown from slightly less than R366-billion in 1994 to almost R937-billion, adjusted for inflation.

South Africans on the whole have also grown richer. In 1994, annual per capita income was $4 519 and, according to ETM Analytics research, it has grown to $6 003 in 2013.

Inequality has not been eradicated, it has become worse, with the Gini coefficient as measured by the World Bank going from 0.57 in 1995 to 0.63 in 2009. (The Gini coefficient is a ratio between 1 and 0, and the closer to 1 a country is, the greater its inequality.)

But research released in October suggests that things may be changing slowly.

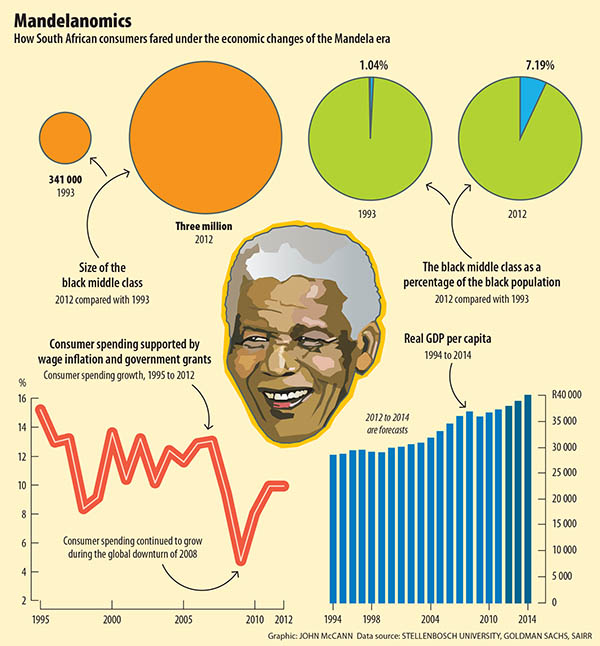

Joint research from the universities of Stellenbosch, Pretoria and the Witwatersrand, examining the country's middle class (defined as a person earning R25 000 a month in 2000 terms) shows it had grown from 3.6-million people in 1993 to 7.2-million in 2012.

Provision of services

The share of black South Africans who make up the middle class has grown from 0.3-million people in 1993 to nearly three milllion in 2012, making up 41.3% of the country's middle class.

The provision of services and welfare support to South Africa's poorest has also increased greatly in the past two decades.

In a recent 20-year review of South Africa, the investment bank Goldman-Sachs noted that social grant spending rose from roughly R57-billion in 2007 to a projected estimate of R104-billion in 2013. The majority of the roughly 16-million beneficiaries of these grants are children.

The report also noted that, between 2001 and 2010, almost 10-million people graduated from the lower living standards measure (LSM) categories of 1 to 4 into the middle-to-upper 5 to 10 bands.

The LSM is a tool for measuring wealth by assessing standards of living.

The number of people in LSM 1 to 4 declined from 52% to 31% between 2001 and 2010. The number of people joining the upper 5 to 10 LSM segments rose from 48% to 69%, at an average of roughly one million people a year during the decade, according to Goldman Sachs.

Challenges remain

The largest group of people, or 12.3-million, are now in the 5 to 6 LSM, from 7.3-million people a decade before.

These figures are not definitive and almost all are subject to the vagaries of statistical modelling and changing methodologies. But they do suggest a trend.

Huge challenges remain but much has changed since Mandela became president, and a very large part of it for the better.