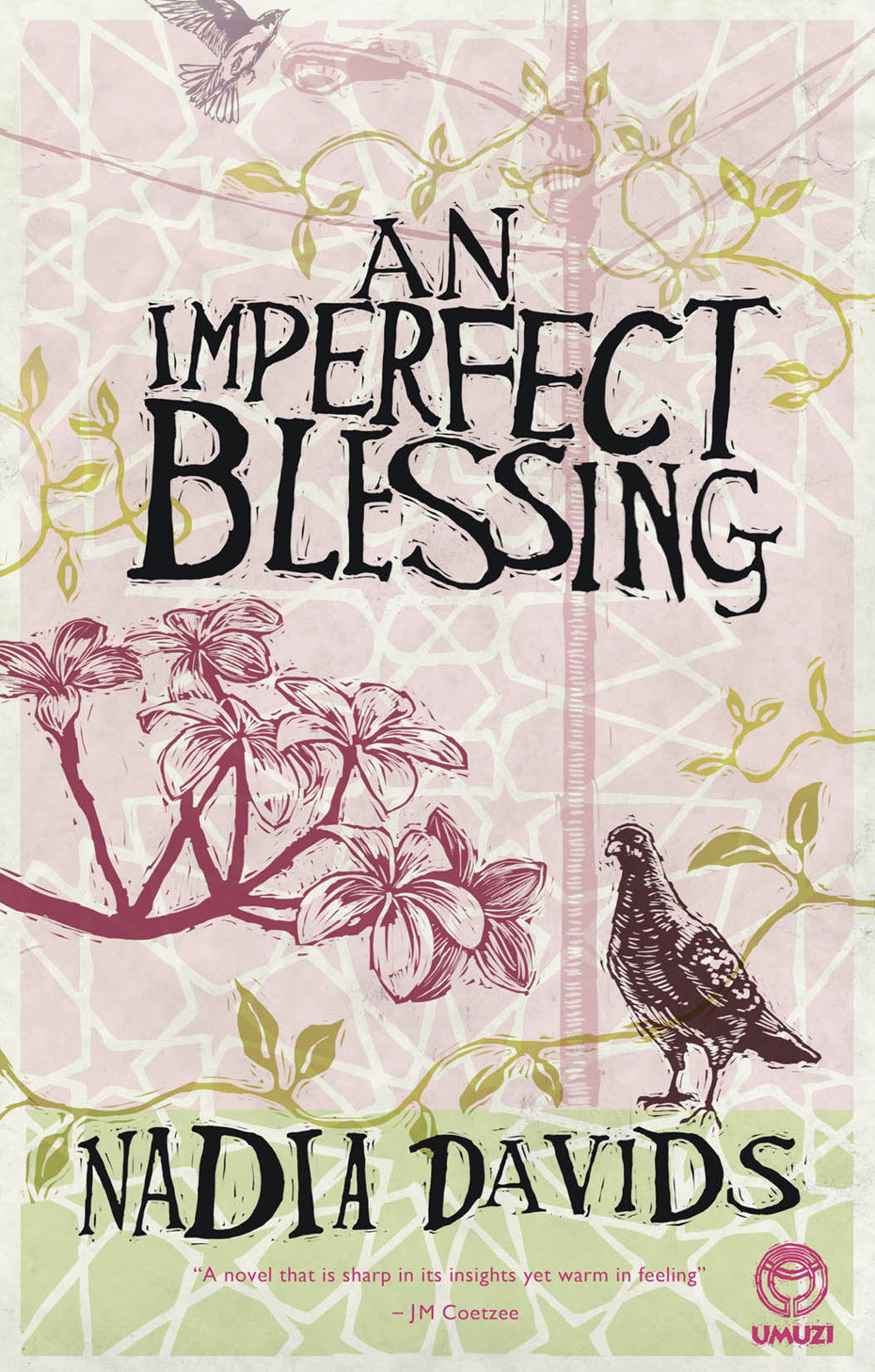

District Six in Cape Town is the setting for Nadia Davids's 'An Imperfect Blessing'.

An Imperfect Blessing

Nadia Davids (Umuzi)

Frangipani blossom and a pigeon adorn the cover, neither as softly romantic as they might seem, both unlikely survivors of the fierce wind that blasts the suburb in which Nadia Davids has set her debut novel. This is Walmer Estate, on the edge of District Six.

At the heart of this novel is Waleed, from a Muslim family, descendant of slaves from Malaysia, and already born when his family and community were forcibly removed from District Six in Cape Town.

Decades later, he still spends time in that ruined wasteland, walking around. “Now, as then, he had three or four books in his bag. One was always his own, a notebook filled with his writing, the others a careful selection … the works of poets and writers of fiction, comrades unmet and unseen …”

This family saga is also the story of Alia, a 14-year-old girl. Waleed is her uncle, but also a poet, intellectual, and political activist who discomforts and unsettles his family. Several long-standing family feuds underpin this portrait of Muslim Cape Town, sandwiched between the mountain and the docks, between white liberals – and neoliberals – of the university and the comrades of Crossroads and Chris Hani’s memorial service.

The narrative runs between 1993 and the mid-1980s, when the people of Crossroads were being harassed by the Witdoeke. Some years later, after a shooting at the local mosque, Alia and her older sister are sent to a private school in a leafy suburb. Nonetheless, influenced by Waleed, they get themselves to Hani’s memorial service in the cathedral in the city centre.

Davids’s portrait of this corner of Cape Town’s hugely diverse society is rich and full of nostalgia; it is also complex and rigorous. She asserts the African identity of this centuries-old community, the principled take of many of their leaders on political issues, their contribution to the struggle, and their survival in what is the still-imperfect blessing of liberation from gross apartheid.

But ignorance and prejudice exist everywhere and the author includes many ruthlessly funny vignettes about their manifestation in Waleed’s community. And even Waleed has difficulty introducing his white, non-Muslim lover to his mother.

Davids recounts in considerable detail celebrations such as weddings and Eid, which offset the teargassing and police dogs. She also acknow-ledges the spiritual core that holds the people together.

Getting up to eat breakfast at 3am during Ramadan, the month of fasting, Alia looks down the street from the balcony of their house: “[She] was alone, secluded … but all around her she could feel people, the people of her street, preparing with faith and purpose … In these hours, in this month, people she’d mocked and glared at suspiciously throughout the rest of the year became, by some unnamed alchemy, as close to her through thought and intention as her own family.”

Davids has already made her mark with two plays, At Her Feet and Cissie, and other writings. An Imperfect Blessing will, one hopes, reach an even wider audience than her plays have done. It’s a novel that should be both respected and cherished.

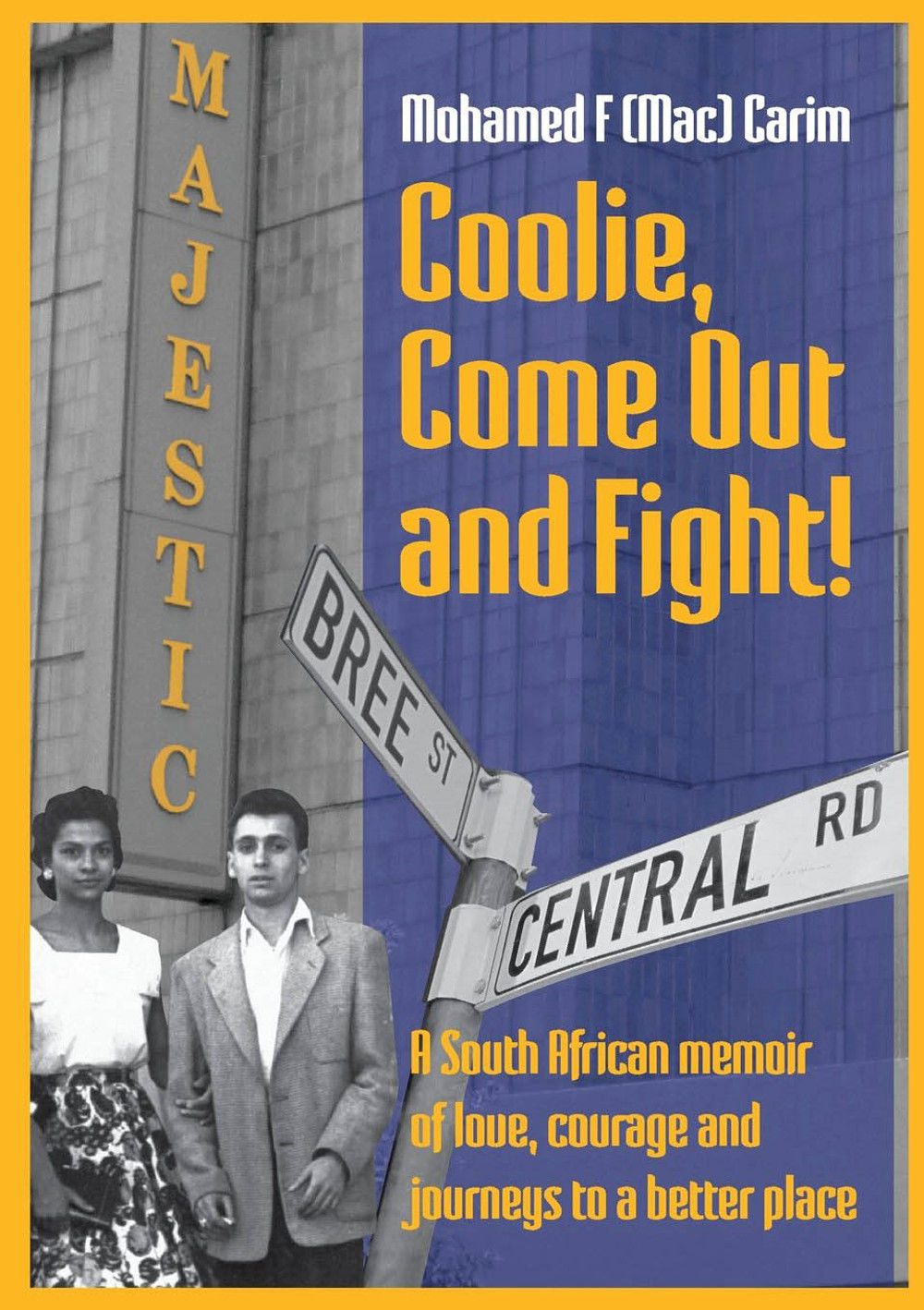

Coolie, Come Out and Fight

Mohamed F (Mac) Carim (Porcupine Press)

This engaging and interesting read is a politically modest “struggle” memoir, which may have been written primarily to please the author, and for his family and friends.

It reasserts the notion cherished by many, including this reviewer, that each individual life is significant and interesting. From humble beginnings in South Africa he and his family, including his siblings, parents and his own wife and children, have achieved remarkable success once they had emigrated.

Carim’s parents had a relentless struggle to establish themselves as traders of one sort or another, always beset by legislation restricting the business operations of South African Indians, and further complicated by the mixed-race status of Carim’s mother – a great beauty who raised six children in conditions of hardship and insecurity.

His memorable and often nostalgic account of his boyhood includes a period in Troyeville, where local white boys liked to call him out of the shop on to the pavement to fight (hence the title of this book). They also spent some time in a flat with a balcony overlooking Market Street in Jajbhai’s Building, in the Johannesburg central business district, and a stone’s throw from the Library Gardens in which they were not allowed to play even when the city centre was deserted over the weekends.

Carim enjoyed these, but points out the contrast with the extremely larney school in Pakistan to which he and his two brothers were sent for a while when the family’s fortunes were in an upswing.

The high adventure of the journey there by ship, and his experiences at the school, showed Carim that life could be better than it was for his family in South Africa.

On his return to South Africa he found the Johannesburg Indian High School in Fordsburg such a comedown that he left before matriculating and started in a variety of jobs – finally ending up with Pepsi South Africa, which led to work all over the world.

In his late teens he and a group of friends led a socially active life (with a few lapses of judgment and brushes with the law) in which good clothes, a cool hairstyle and dancing played a big part.

Luckily one of them had a car, a 1949 Chevy. When Carim was just 22 he married Hajoo – the start of a long and happy marriage.

The text shows signs of a battle to compress and streamline the narrative of complicated life events; a more ruthless edit may have produced a more elegant book, but lost its special savour.

Carim’s storytelling is a lively mix of fact and opinion, and he has an eye for beauty.

I especially enjoyed his little riff on white lace curtains as a symbol of Hajoo’s determination to keep things good and tranquil in the family home.

Similarly enriching are his meditations on people in his life from whom he learned something useful – such as the stupidity of racism from his friendship with Sally van Rensburg, a poor white girl in Troyeville, and from a Jewish teacher in Pakistan he learned that confidence and good planning lead to success.

From Johannesburg to Lahore, and later on to Nigeria and Canada, this is a rich and memorable story.