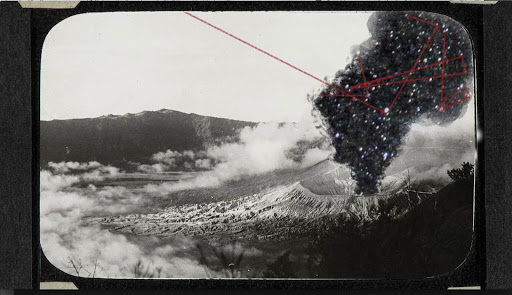

Polyhedra, still 5 from Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s book There Are Mechanisms in Place (2018), published by Michaelis Galleries, UCT

In Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s There Are Mechanisms in Place (2018), the hand of human intervention is present in nearly every evocation of nature. Through drawing, video, and installation, Sunstrum draws the viewer into intricate and detailed compositions that subsequently zoom out to offer an expanded view of structural mechanisms, such as land purveyance and cosmological analyses, in concurrent operation. There Are Mechanisms in Place offers an opportunity to reflect on the artist’s concerns regarding land, particularly the surveillance and control thereof. Sunstrum further explores the mediation of people’s relationship to land within the realm of technology, politics, memory and the aesthetic.

In Study for “Homing Device” (2018), the skies are replaced by the X and Y axes of a mathematical matrix. The scientific precision of the grid starts to resemble a dark void: the birds’ current locations are charted, and yet still unknown. The memory work of the bird is measured against the geometry of flight. The installation comprised a number of screens and blackboard-like surfaces, with light emitting from both digital and overhead projectors, which, in and of itself, produced a disorienting light-blinding effect for the exhibition visitors.

The timing of this exhibition coincides with a crucial political juncture in the fight for land rights in South Africa — a moment in which the Constitution’s provisions for land expropriation were being questioned. Locating it in Cape Town, where issues around land restitution have been contested since the arrival of the first Dutch East India Company ships, is particularly salient. The beauty of the city’s vistas and shorelines become fraught when placed adjacent to its near-erased historical and indigenous narratives.

Additionally, the battle of astronomical real-estate prices and the looming threat of rising sea levels manifest into a reality of their own. Something —possibly sinister, supernatural, or simply devastating — lingers, too, in Sunstrum’s work, generating a pervading sense of unease and apprehension.

In the film Polyhedra (2018), a hand appears to calculate the threat of potential violence of mid-eruption volcanoes with a red cartographic marker, and maps the cosmological meaning of the disaster on Earth.

In the film Polyhedra (2018), a hand appears to calculate the threat of potential violence of mid-eruption volcanoes with a red cartographic marker, and maps the cosmological meaning of the disaster on Earth.

Sunstrum’s two-channel film Polyhedra (2018) is a montage comprising historical photographs, drawings and diagrams. In the film, a hand appears to calculate the threat of potential violence of mid-eruption volcanoes with a red cartographic marker, and maps the cosmological meaning of the disaster on Earth. Interspersed with these marked and analysed scenes are revolving night-starred skies, reminding the viewer of the minute scale of the volcano in the scheme of the galaxy and the universe. The two parts of the film mirror each other — playing in parallel — each whirring and ticking away indefinitely.

During my education at Michaelis School of Fine Art at the University of Cape Town, I was introduced to the Kantian interpretation of the sublime in the study of aesthetics. In Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime (1764), the philosopher Immanuel Kant discusses the distinctions between the beautiful and the sublime and how these phenomena are experienced by “the sexes”, “nationalities” and, by extension, races.

The Kantian sublime, as it relates to questions of the aesthetic and the experience of natural wonder or the intellectual inability to comprehend the infinite — is made distinct and divorced from his writings on racial types. The “national characters” on the intellectual capabilities of women, among other topics, have undoubtedly informed far-reaching ideas about race, rationality and intelligence. The sublime is based on a principle of terror that is assumed to be detached from the (then) concurrent claim of territories by European powers.

In thinking about the legacies of colonial cartography and anthropology as forms of territorialisation, it is worthwhile to consider the limits of this paradigm and its links, however tangential, to the colonial psyche and terror of possession and control of land and the natural landscape, and further, the ways in which the landscape undergoes physical changes and relationships to land and place are disrupted, as a result of colonial settlement.

There Are Mechanisms in Place posits that the all-encompassing physicality of the landscape does not reference an “abstract” danger, but one that is created by both nature and human design. (Polyhedra, still 3)

There Are Mechanisms in Place posits that the all-encompassing physicality of the landscape does not reference an “abstract” danger, but one that is created by both nature and human design. (Polyhedra, still 3)

In contemporary aesthetic philosophy, applications of the “sublime” have extended beyond the “natural”, to include what theorist Ned O’Gorman describes as the paradoxical “political sublime”: disasters of human creation. Although the philosophical notion of the sublime has occupied thinkers since its inception, newer evocations of the concept allow one to consider the “awe-inspiring” in the same breath as “disaster”. As an inherently apolitical idea, the sublime refers to the overwhelming sensation or dispassionate response one experiences when encountering natural phenomena.

Such readings of the sublime reveal the seemingly apolitical, economical, and “logical” ways in which landscapes have been observed within the lens of Western philosophy in the past. To use the sublime, a concept so commonly taught in art history studies of the aesthetic, is thus equally inherently limited in trying to conceive of the political implications of landscape, and the traditions of its representation.

In her essay The African Oceans: Tracing the Sea as Memory of Slavery in South African Literature and Culture, Gabeba Baderoon alludes to the limitations of European landscape painting in representing the harsh realities of enslavement and slave labour at the Cape. In emphasising the overwhelming beauty of the city’s mountains and vistas, she asserts: “The colonial city represented in such picturesque painting was founded on slave labour, but these views of Cape Town also rendered that labour invisible … The 19th-century panoramas of the Cape painted from Signal Hill directed the gaze away from the sea towards the city with its detailed divisions, the looming height of Table Mountain with its crags and hiding places and the bodies whose signs of labour or leisure signalled whether they were slaves or slave-owners.

”To these ends, in discussing the prospect of catastrophe, it is then productive to consider the landscape as a repository for memory, and the ways in which the Western paradigmatic view of nature hinders such readings. Lose Your Mother: A Journey along the Atlantic Slave Route, a memoir and historical account by Saidiya Hartman, provides an important counterpoint with which to consider moments or acts of an engulfing scale. Hartman’s personal experiences of the Ghanaian coast — once the floodgates of the slave trade — are placed within the backdrop of historical data and reflections on local interpretations of the slave economy.

In Study for “Homing Device” (2018), the scientific precision of the grid starts to resemble a dark void: the birds’ current locations are charted, and yet still unknown.

In Study for “Homing Device” (2018), the scientific precision of the grid starts to resemble a dark void: the birds’ current locations are charted, and yet still unknown.

Visiting Elmina Castle, a former slave port built in 1482, Hartman is shocked to find that she is not able to perceive the ghosts of the past lingering at the site: “Taking the festival of colour and sound before me, what I found troubling was that the scars of slavery were no more apparent in Elmina than in Boston or Rhode Island or Charleston (or Lisbon or Bristol or Nantes). Only the blessings of the slave trade remained, according to the town’s residents, by which they meant their modernity […] The captives were scattered. Those I wanted to harm were gone. The banks, shipping companies, insurers, nation-states, manufacturers, and ports still thrived, but they were too powerful for any blow or kick or complaint of mine to make them cry out in pain or wish they were dead.”

As Hartman describes, the vestiges of colonial power remain in Elmina. The backbone of modern infrastructure, their dismantling could upend the economies of the town. In this particular instance, the reliance of the residents on these structures (mechanisms), and the strength of the colonial imprint obliterates the horror of human trade until its memory is imperceptible.

In the collage and drawing on paper titled Show Me Your Maths (2016), equally disoriented, floating bodies descend into matrixes and star charts. The words “teach me your maths” form the depths of the picture plane below, repeated persistently in light tones of pencil, black and gleaming gold. On entering the exhibition space, one is confronted by Cathedral (2016), in which mountains form the pinnacles from which observation points are perched, the night’s skies navigated, and future rains predicted. In Untitled (2016), a drawing on paper, a portrait of a mother and child, other mountains become bodies and vice-versa. These peaks form the child’s blanket, the mother’s dress and, ultimately, frames their environment.

Considering physical and historical erasures, I am led to probe further into the legacies of ancestral and inherited trauma as it pertains to the loss of place, and of home. In the works on paper, projections, installations and film-based media, There Are Mechanisms in Place posits that the all-encompassing physicality of the landscape does not reference an “abstract” danger, but one that is created by both nature and human design.

Cape Town itself, as a site and history, thus becomes a vital stage for this scene — a city lost in its own cyclical battles with colonial power, and blinded by its own beauty.

This essay is taken from Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum’s There Are Mechanisms in Place (Michaelis Galleries, UCT), a creative book on Sunstrum’s work. The book follows the artist’s solo exhibition of the same name presented at Michaelis Galleries from August 23 to September 21, 2018. It is edited by Nkule Mabaso and Nomusa Makhubu.