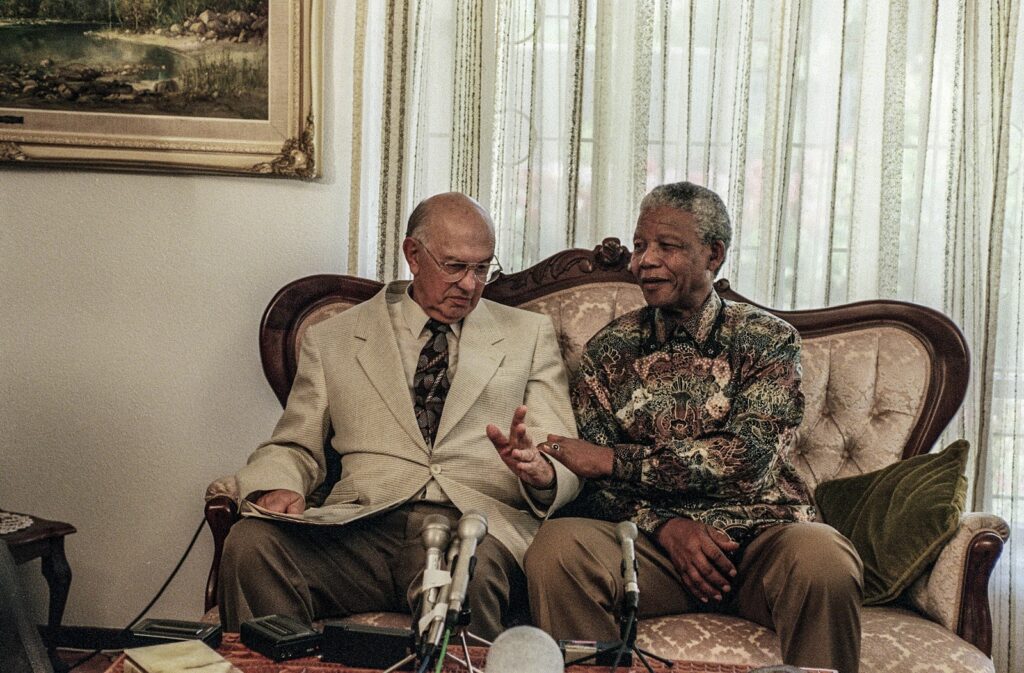

Nelson Mandela and FW de Klerk after breakthrough talks in Cape Town on May 5 1990 (Benny Goo/Gallo Images/Oryx Media Archive)

Kobie Coetsee was the old white National Party (NP) minister of justice in the last years of Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment, and played a key role in his release. Just how much of a role he played has been partly obscured by the way this history has been written so far, and his role has been contested, in particular by the former state security agent, Niel Barnard, who was involved in parallel talks with the ANC and leaders such as Thabo Mbeki.

But Coetsee’s role can now be described more accurately. Details to do with the process of Mandela’s release, prefigured by then-president FW de Klerk’s unbanning of the ANC and other liberation movements in February 1990, is to be found in Jan-Ad Stemmet and Riaan de Villiers’s book, Prisoner 913: The Release of Nelson Mandela (Tafelberg).

The material used in the book is rather extraordinary. It’s part of the Coetsee archive, which he took with him when he left government, and which went to the University of the Free State after his death. There it was discovered by Stemmet 13 years after Coetsee had invited him to write his biography, a job that, ironically, would have included access to his archive. In 2000, Coetsee had promised Stemmet some “bombs” of information from the archive — but then died suddenly two days later.

Stemmet initially worked with academic Willie Esterhuyse on the vast Coetsee archive (13 000 pages on the jailed Mandela alone!), then brought in veteran journalist and editor De Villiers to home in on the material related to Mandela’s release and to turn it into this book.

The material is extraordinary, too, because much of it is transcriptions of recordings of Mandela’s conversations while he was in jail, as members of the state security forces eavesdropped on him. These recordings were set up and monitored by Coetsee himself, and not part of the other bugging by state spy agencies such as the National Intelligence Agency.

This was Coetsee’s own “monitoring” initiative, which continued even as he had increasingly complex discussions with Mandela about his meeting PW Botha, president until 1989, and later his successor, FW de Klerk, as well as on the beginnings of a process that would lead to the Codesa negotiations that developed a settlement between the NP and the ANC and, ultimately, ushered in a new, truly democratic South Africa.

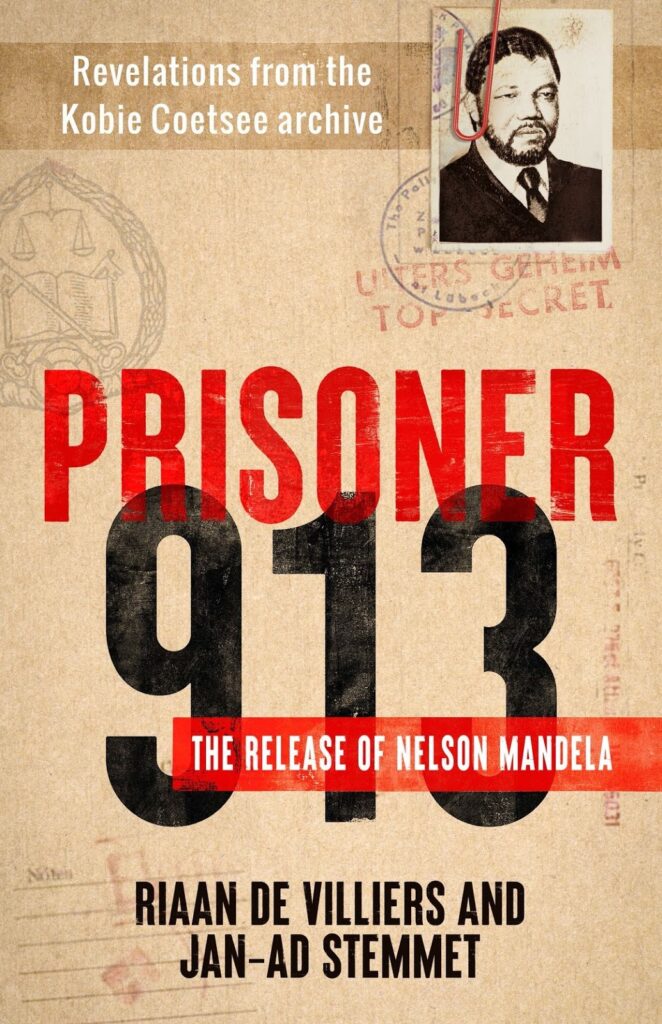

The title of Riaan de Lilliers and Jan-As Stemmet’s book refers to Mandela’s initial “general” prison number (Tafelberg)

The title of Riaan de Lilliers and Jan-As Stemmet’s book refers to Mandela’s initial “general” prison number (Tafelberg)

Mandela is referred to as “Prisoner 913”, or just “913”, because that was his original “general” prison number, which Coetsee and others stuck with, despite Mandela having acquired the more famous 46664 when he landed on Robben Island in 1964.

The book offers a full picture (although there are still some gaps) of Mandela’s famous letter to Botha, and fills in much detail about the process leading up to his release that Mandela himself, in Long Walk to Freedom, omits. In that autobiography, which De Villiers half-jokingly refers to as “the Disney version” of Mandela’s life story, Mandela “jumps from the meeting with FW de Klerk to the release”, says De Villiers, although a considerable amount of back-and-forth, and indirection, took place in that gap.

“In his account of the FW meeting,” says De Villiers, “Mandela says ‘We sized each other up’, but FW, in fact, made concrete proposals. FW’s announcement on February 2 1990 was about meeting the terms of the Harare Declaration” — and the ANC’s declaration of August 1989 essentially set out the organisation’s terms for negotiations with the white NP government, and was based in part on Mandela’s proposals while in jail.

The book shows the long, often zigzagging path that Mandela took in what you might call his “reaching out” to the white government, at first declaredly a personal, individual initiative, only later endorsed (and sometimes grudgingly) by the ANC. It shows, too, that the ANC in exile, which had, in fact, begun secret “talks about talks” with the NP, wasn’t always upfront with Mandela about what was going on.

Mandela had been in touch with Oliver Tambo, through a secret channel (although the NP knew about it) set up by his former fellow prisoner Mac Maharaj, and Mandela had made it clear to Tambo what he was doing.

Later, however, when Mandela spoke to Thabo Mbeki and Alfred Nzo in Lusaka from prison, it’s clear from the transcript of the call, recorded by the state security forces, that Mbeki was not being entirely honest with Mandela about what was going on — given his own contacts with figures in the white state apparatus such as Barnard.

Prisoner 913 shows how Mandela’s thinking about the process changed. At one point, as De Villiers says, “Mandela thought he and FW would thrash it out. But, for FW, Mandela was a sideshow.” After their initial meeting, some time before February 1990, they did not meet privately again.

Thousands of protesters march for the release of anti-apartheid activist, Nelson Mandela, Johannesburg, South Africa, February 02, 1990. (Photo by Media24 Archives / Gallo Images via Getty Images / Getty Images)

Thousands of protesters march for the release of anti-apartheid activist, Nelson Mandela, Johannesburg, South Africa, February 02, 1990. (Photo by Media24 Archives / Gallo Images via Getty Images / Getty Images)

Mandela had made a proposal to the ANC that there would be a “simultaneous declaration” from the ANC and the NP, and that proposal was carried to the ANC in Lusaka by Cyril Ramaphosa, but “we still don’t know exactly what the proposal was”. The ANC seems to have shot that proposal down, but did go on to make the Harare Declaration.

There is much that shows how isolated Mandela was, and how faltering were his steps towards talking to the NP government. His letter to Botha was published in South, and it came across as “embarrassingly outdated”, as De Villiers puts it. There was an immediate attempt at “damage control” by the ANC, which noted that Mandela had been in jail a long time, implying he’d lost touch with the key areas of struggle.

“I personally believe the ANC was keeping Mandela at arm’s length at that stage,” says De Villiers. Mandela had initiated the contacts with the white government on his own, and there were suspicions on the part of fellow ANC leaders such as Govan Mbeki, who was released ahead of Mandela (in 1987), that Mandela had been co-opted in some way.

Mbeki recommended that the ANC distance itself from Mandela. (Which is rather ironic in that Govan’s son, Thabo, was already in direct contact with the NP state.)

There was a view, too, at the time, that the NP’s strategy was to split Mandela from the ANC, viewing him as more “moderate” than what it saw as the communist-inspired ANC in exile. But, says De Villiers, in the archive “there is no indication of Coetsee or others wanting to split Mandela off from the ANC”.

In fact, says De Villiers, “From early on, it’s clear Coetsee admired Mandela. He was essentially prepping him for the presidency.”

Coetsee had been an advocate of the unconditional release of Mandela from the mid-1980s, a position that didn’t work for Botha, but Coetsee appears to have continued to hold that view throughout, and to have worked to make it happen.

South African President Nelson Mandela (r) holds the arm of former apartheid hardline President Pieter W. Botha as they meet 21 November 1995. P. W. Botha, whose iron-fisted rule of South Africa from 1978 until 1989 earned him the nickname “Great Crocodile”, received the South African President in his house in Wilderness. (Photo by WALTER DHLADHLA / AFP)

South African President Nelson Mandela (r) holds the arm of former apartheid hardline President Pieter W. Botha as they meet 21 November 1995. P. W. Botha, whose iron-fisted rule of South Africa from 1978 until 1989 earned him the nickname “Great Crocodile”, received the South African President in his house in Wilderness. (Photo by WALTER DHLADHLA / AFP)

Coetsee himself emerges as a strange and, still, in many ways, an enigmatic figure. His motivations are not fully clear, beyond his relish in playing the political game from a position of power — and what appears to be a genuine, meaningful connection with Mandela himself.

Writer Gavin Evans has referred to Coetsee as “gnome-like”, but he may as well have said “gnomic”. Coetsee seems to have felt, in the long run, that he had not been given sufficient credit for his role in the liberation of South Africa from apartheid — or his role had not been accurately accounted for, hence his offer in 2000 to Stemmet.

The book also has some eye-opening revelations about Mandela’s relationship with his wife Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, who caused him (and the ANC, and the internal democratic movement) a great deal of trouble while, at the same time, providing a comforting presence for Mandela, whom she continued to visit, with determined regularity, throughout his imprisonment.

The ambivalences here are spelled out in an amazingly frank conversation between Mandela, his daughter Zenani and her husband Muzi Dlamini, which was not bugged electronically, but recorded in notes taken by one or other prison official who was present.

It shows that Mandela was aware of Madikizela-Mandela’s affairs with other men, and even that, in his view, she had been responsible for tipping off the police as to his whereabouts in 1962, when he was finally arrested after spending nearly a year and a half on the run. Madikizela-Mandela seems to have been in an “intimate relationship” with someone who was a police informer.

The material that Stemmet and De Villiers have mined from Coetsee’s secret archive and shaped into this book make fascinating reading for anyone interested in the inside story of how the process of negotiations to create a new South Africa developed, as well as those drawn to Mandela as a historical — and history-making — figure.

Prisoner 913 mostly leaves the interpretation of this material to the reader. “Our own comment is cut to a minimum,” says De Villiers. “We concentrated on putting this material in the public domain and we leave readers to draw their own conclusions. It’s good to see scholars situating this material in their own scholarship.”