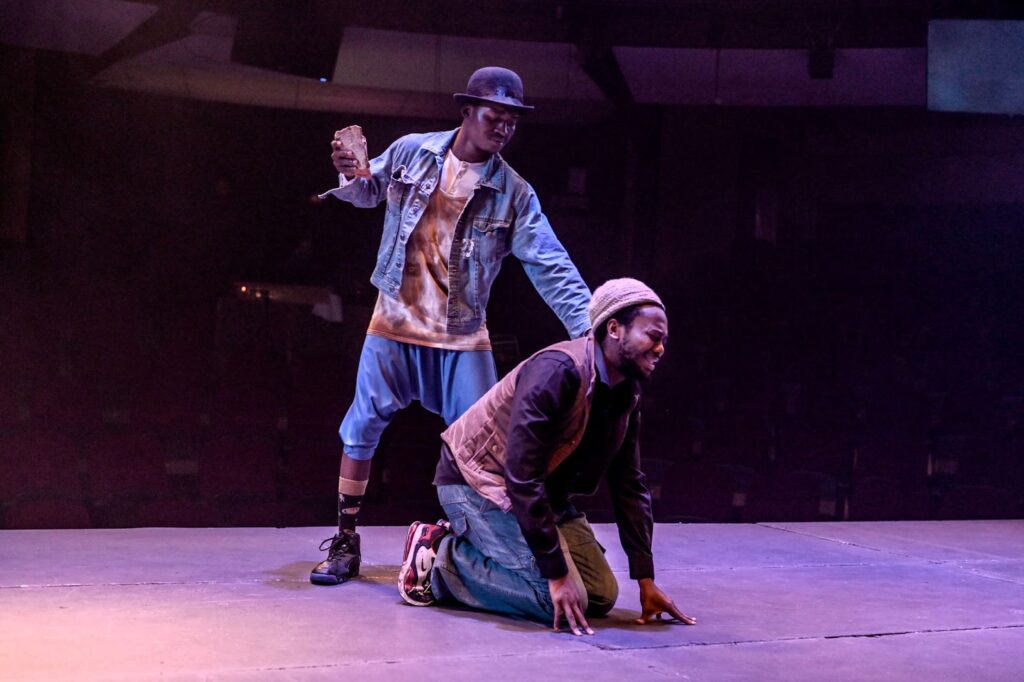

Waiting for no one: Hungani Ndlovu and Charlie Bouguenon in Pass Over.

(Photo: Suzy Bernstein)

The setting is now, right now: a ghetto street. A lamppost. Night. But also 1855: a plantation. Day. But also 13th century BCE: Egypt, a city built by slaves. Night. But also Alexandra: Collins Khoza’s body. Night. But also May 25 2020: George Floyd’s neck. Day. But also Mthokozisi Ntumba Street, Braamfontein: Fees Must Fall protest. Day. This is the where and when playwright Antoinette Nwandu raises her pistol of a script like a staff and ushers us through our Pass Over.

Inspired by Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, an absurd classic famously described as “a play where nothing happens — twice,” Pass Over not only echoes the structure of its inspiration — two men waiting for deliverance from their squalid paralysis by a mysterious character, it also advances the story.

Nwandu achieves this advancement by melding Waiting for Godot with the story of the Passover in the book of Exodus, stretching the spinal theme from a waiting for salvation to that of a taking thereof. It is as if to say that life affords two white men the privilege of waiting whiling away time over philosophies of existence, while black bodies bear such grand resemblance to a bull’s-eye that a bullet may stray and cease their waiting.

While Nwandu borrows Beckett’s blend of cutting, crackling comedy and categorical gloom, there is one major, crucial difference to her play. Beckett’s vagrants existed inside an anywhere, anytime vacuum; Nwandu’s young men are grounded in a reality that’s horrifically recognisable.

The first protagonist is Moses (Khathu Ramabulana), a black young man from the ghetto. Brokenhearted. Courageous. Alpha. Angry. Sad. But also a slave driver. But also the prophesied leader of God’s chosen. But also a human rights activist.

But also a political party leader. The second is Kitch (Hungani Ndlovu), a black young man from the ghetto and Moses’ best friend. Jovial. Loyal. Kind. Naïve. A lovely friend. But also a slave. But also one of God’s chosen. But also a rally foot soldier. But also a political party vice.

The play is deeply concerned with how pervasive systems of violence and oppression have operated consistently throughout human history. A play about the epidemic of police killing unarmed black men, it is just as much a play about how the powerful have always sought to keep the oppressed contained, pressed face flat on the pavement.

The cynosure of the play is a game called “promised land top ten,” where Moses and Kitch conjure their wish list on the other side of the passover: collard greens and pinto beans, a drawer full of clean socks, a beloved brother back from the dead. Meanwhile the Red Sea of white-jiggered society’s permission keeps them locked to the block.

Ramabulana and Ndlovu ricochet from mirthful clowning to urgent, existential despair and back again. There’s an arresting tenderness to their exchanges, the way there often is just below the bantering, back-chatting surface of men’s friendships. The poignant bond of love between the two men is acutely alive. They vividly convey their characters’ intriguing combination of strength and desperation, as well as the dark humour to which they resort to cope with their barren existence.

Hungani Ndlovu and Khathu Ramabulana ricochet from mirthful clowning to urgent, existential despair and back again. (Photo: Suzy Bernstein)

Hungani Ndlovu and Khathu Ramabulana ricochet from mirthful clowning to urgent, existential despair and back again. (Photo: Suzy Bernstein)

While the play indubiously dumps contemporary US racism on the sidewalk, it also filters through timeless, bedrock questions of how people wrestle with the idea of dignity and freedom when they’re trapped by power, both hard (police) and soft (elites who think themselves saviours).

The antagonist is “The Man” (Charlie Bouguenon), who arrives as “Master”, an off-course white male clad in an all white suit. Out of his element. Earnest. Wholesome. Terrified. But also a plantation owner. But also Pharaoh’s son. But also a government official. But also a corporate executive. He again arrives as “Ossifer”, a white policeman. A law enforcer. Not from around here, but always around. Pragmatic. Intimidating. Also terrified. But also a patroller. But also a soldier in Pharaoh’s army. But also from around here. But also a black policeman.

The performances of the three actors resemble resounding gunshots, the text akin to their bodies, and the American accent seeming to have lost its weight from the four weeks’ exercise of performances, and now light on their fervid tongues.

If there were a weakness we could identify, it would have to be that it feels a bit overlong, with the Biblical references and stories, in particular, jutting out a little awkwardly from Nwandu’s script and the voices of the characters. It is more effective thematically than as drama. The dialogue at times feels aimless and repetitive, a Godot-esque type approach I suppose. The narrative lurches confusingly, and some of the symbolism and its meanings prove elusive.

There is however no denying that this here is an agonizing, intense and clever piece of theatre that, unlike the ”nothing to be done” motif in Godot, provides a crystal-clear directive: “Stop killing us!” – making this a play where a shift happens.

Staying in tune with the audaciously bold dramaturgy of varied timelines in one act on an almost bare stage, director James Ngcobo brought in audiovisual designer Thabang Lehobye to animate projections that will teleport us from one age to another, a challenge generously met with the collaboration of lighting designer Mandla Mtshali, sound designer Ntuthuko Mbuyazi and musical composer Kabomo Vilakazi.

Staged for the first time in 2018 at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre, and instantly flagging playwright Antoinette Nwandu as a significant bold new voice, Pass Over made its South African debut under the direction of the Market Theatre’s artistic director James Ngcobo as part of the annual commemoration of Black History Month in partnership with the US Mission.

Although relatable to not only the times but also our own experiences in South Africa, there is an acute criticism regarding the Market Theatre’s choice of staging American plays when there are enough able playwrights in the country who can be commissioned to write stories that not only relate, but are homegrown.

Responding to the muttered censure, Ngcobo says, “Stories are universal, we need not be myopic when dealing with them. We cannot always be creating and staging South African stories, how then can we challenge ourselves. I seek to always challenge myself as a director and the actors I collaborate with. When an actor can master an American accent here at home, surely they will be fit for a role abroad; this was evident when I took three actors with me to Washington, DC and remarkable work was done … This partnership has opened doors to South African theatre, and introduces our patrons from all walks of life to more than just their immediate world.”

Pass Over was part of the Market Theatre’s Black History Month programme