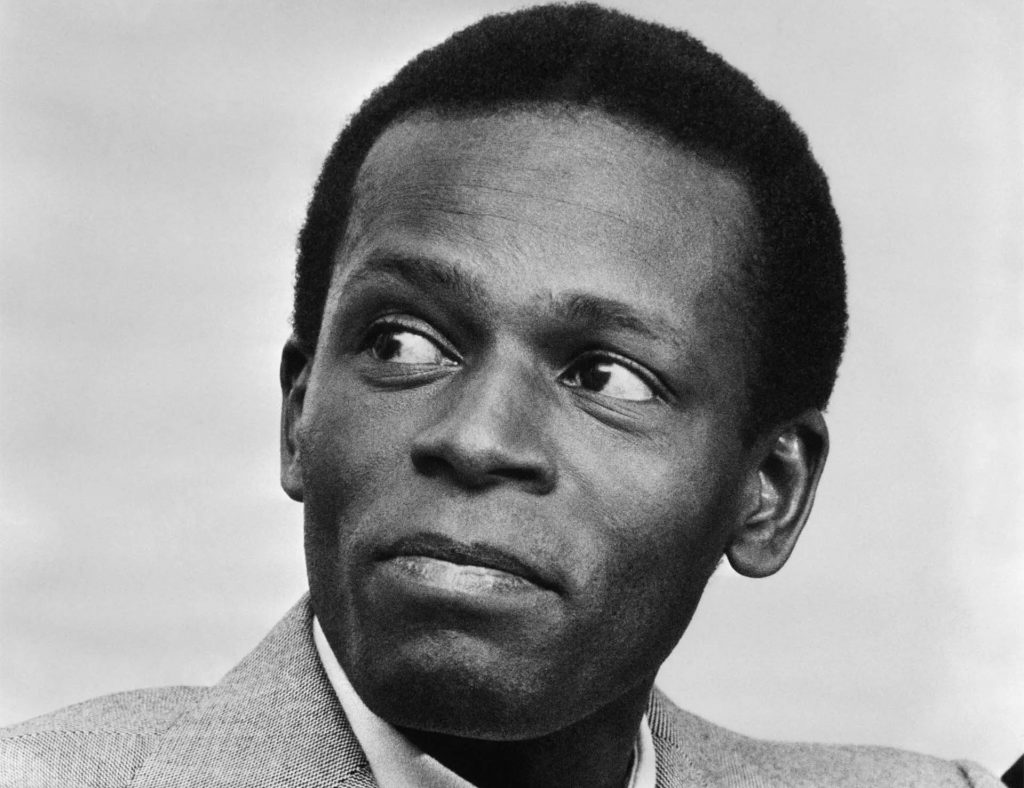

The former Angolan autocrat, who was president from 1979 to 2017, built up the wealth of his family and that of his generals at the expense of the citizens. (Photo by MARCO LONGARI / AFP)

After a two-year retirement in Barcelona, Spain, and a battle with ill health, Angola’s former president, José Eduardo dos Santos, died at the age of 79 on 8 July. He ruled with an iron-fist for 38 years, treating one of Africa’s richest countries as his personal fiefdom.

Dos Santos was born in 1942 in Sambizanga, a district in Luanda, Angola’s capital. Angola was ruled by Portugal at the time, itself ruled by António Salazar, among the last of Europe’s dictators. Angola was one of Portugal’s few African colonies. Dos Santos joined the MPLA in 1962 as part of Angola’s largely unsuccessful anti-colonial war against Portugal from 1961 to 1975. During that time, Dos Santos underwent political training in Moscow and became a petroleum engineer in Azerbaijan. Angola secured liberation from Portugal five years after Salazar’s death in 1970.

Within a year of independence, Angola plunged into civil war. A fractious coalition of nationalist movements that had banded together to upend colonial rule was torn asunder. Angola became a physical proxy battle site for Cold War protagonists. Russia and Cuba supported the MPLA, which went to war with Unita, led by Jonas Savimbi, himself an aspiring dictator. South Africa’s apartheid government, along with the CIA, supported Savimbi against the MPLA.

The MPLA was not exactly a united party itself and, in 1977, it suffered a failed coup attempt. Dos Santos had by then become part of the MPLA’s political bureau, a tight-knit group of 10 under the presidency of Agostinho Neto. The coup was spearheaded by Nito Alves. Dos Santos took Alves’s place in Neto’s cabinet as the minister of the interior. Coup leaders were caught and indiscriminately killed.

I argued in my book on the evolution of Angola’s political economy that the coup attempt proved a critical juncture. Neto was able to consolidate the MPLA while simultaneously creating a national ambience of fear. Although the figures are still disputed, estimates suggest that roughly 30 000 people were killed in the aftermath.

Neto died on a Russian operating table in 1979. Dos Santos ascended to the head of the party and became president of the country. Within six years, he had purged the party of its intellectual heavyweights, the most influential of which was Lúcio Lara, the party’s secretary general who had been targeted in the coup attempt but survived. He was instrumental in Dos Santos’s succession to the presidency and part of the central core that established the MPLA and supported Neto after two other founding members had been crowded out — Mário de Andrade and Viriato da Cruz. In 1985, Dos Santos removed Lara from the political bureau. He was suspicious of Lara and a group around him who he considered to be a liability to consolidating personal control of the MPLA.

This move was just one example of Dos Santos’s power-consolidating strategy in the MPLA. He played expert musical chairs among his inner circle, figuratively eliminating anyone with suspected political ambition and thwarting the probability of successful coup attempts.

Under cover of the civil war, which lasted 27 years, Dos Santos allowed his generals to become extremely wealthy, thereby eroding the chances of a military coup. He infamously allowed oil-for-diamond exchanges between his generals and Unita generals. Soldiers who shot each other by day traded contraband at night.

Dos Santos also played off Cold War opponents against each other. One of the differentiating hallmarks of Dos Santos’s autocracy was the competence of Sonangol, the state-owned oil company. And herein lies one of the Cold War’s greatest paradoxes. Sonangol leased deep-water oil blocks to US majors, which pumped oil that was shipped to the US and beyond. US oil production (and consumption) literally funded the MPLA (alongside Russia’s contribution, largely through oil-for-arms deals).

Dos Santos knew that the CIA would not allow Unita to bomb those oil fields, because any US civilian casualties would eliminate the agency’s ability to support Unita. Dos Santos used his oil rents, which far outweighed the value of Unita’s diamond rents, to wage war and consolidate his autocracy. Savimbi was not amenable to democratic advances and went back to the bush in 1992 after a failed peace attempt and national elections to wage war for another 10 years before his eventual assassination in 2002.

From 2002 onwards, Dos Santos had an unprecedented opportunity to rebuild Angola. The best book on the subject is Magnificent and Beggar Land by Oxford scholar Ricardo Soares de Oliveira. He describes in detail the white elephants — infrastructure projects (largely resource-for-infrastructure contracts with Chinese companies) with no economic endgame in mind — and the way in which Sonangol became a shadow state through its complex web of subsidiaries.

Instead of building broad-based development, Dos Santos ensured that wealth flowed only to a dynasty of crony capitalists, family members and an inner circle of political elites. Patronage flowed from there to sustain just enough political support for the MPLA. As Soares de Oliveira put it, “The parallel system didn’t merely survive in very different circumstances: it was recalibrated, diversified and grew out of all recognition into a giant web of privileges and resource extraction.”

This kleptocratic game was all good and well — from the perspective of an entrenched dictator — but it was disastrous for ordinary Angolans, the majority of whom still live on under $2 a day. For Dos Santos, the game lasted until 2014, when the oil price peaked and subsequently crashed. The crash dissipated the rent streams that had fuelled his continuation in power. Dos Santos went from Angola’s “architect of peace” to a liability for the MPLA.

His strategic mistake was that he “allowed political comebacks among those who seemed penitent but proved to be a more credible threat than anticipated”, something he would probably not have succumbed to earlier in his career. One example will suffice. Dos Santos removed João Lourenço from his position as MPLA secretary general in 2003 for publicly expressing ambition to succeed Dos Santos as president (after Dos Santos had hinted that he would retire). Lourenço launched a comeback and was appointed as Minister of Defence in 2014.

Dos Santos could see the writing on the wall and began to make contingency plans to protect himself in the event of having to relinquish power. He appointed José Filomeno, his son, as a succession option, as well as appointing him head of Angola’s $5-billion Sovereign Wealth Fund. In June 2016, he fired the Sonangol board and appointed his daughter, Isabel, as the chief executive. He also attempted to provide them with immunity from presidential interference.

The MPLA re-elected Dos Santos as its president in August 2016 and placed him first on its candidate list ahead of the 2017 national elections. Lourenço was appointed as vice- president. In February 2017, Dos Santos again announced that he would step down as country president and not be eligible for the 2017 national elections. He would nonetheless remain as MPLA president until 2022. The MPLA central committee then reneged and announced Lourenço as its nominee for the presidential candidate and head of the party.

While the move was widely perceived at the time as continuous with the old guard, choosing Lourenço was, in the eyes of some scholars, more likely “the culmination of a protracted tug-of-war between the presidency and important segments of the party … [and his] rise was hardly an optimal outcome for Dos Santos”. One way for even an entrenched dictator to lose power is to place family members in prime positions ahead of party loyalists.

These moves — re-embracing Lourenço and favouring family — have proved sub-optimal for the Dos Santos family, but potentially good for Angola’s longer-term prospects. In 2019, Isabel’s Angolan assets were frozen. In 2020, Filomeno was jailed by an Angolan court for five years for alleged fraud of more than $500-million.

The jury is still out on Lourenço’s dedication to transformation, both politically and economically. National elections are scheduled for August and the opposition — led by a resurgent Unita — looks more promising than in previous years. Lourenço’s test will largely be whether he refrains from repression, the favoured tool of his predecessor.

Regarding Dos Santos’s death, the Lourenço government said he had “governed for many years, with clairvoyance and humanism, the destinies of the Angolan nation in very difficult moments”. To the contrary, his legacy is best summed up by long-time critic Rafael Marques de Morais, cited in the Financial Times, as “the looting and kidnapping of a country, bent to the interests of the oligarchy he created”. Dos Santos has left behind a “feudal suzerainty”.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.