For people like unemployed mother Palesa Motsamayi it is difficult to get credit such as mortgages because they do not hold the title deeds to their homes.

Joe “Unsecured” Soap has bankers salivating, credit regulators and analysts jumpy and the South African Reserve Bank reassuring just about everybody who will listen that the local banking sector is in no way at risk of a meltdown. But just who is Mr Soap?

Joe “Unsecured” Soap has bankers salivating, credit regulators and analysts jumpy and the South African Reserve Bank reassuring just about everybody who will listen that the local banking sector is in no way at risk of a meltdown. But just who is Mr Soap?

He is the unsecured borrower – anybody who takes credit from a bank or lender, but has no security or collateral against the loan. According to experts, South Africans from all walks of life are doing more of this type of borrowing for various reasons.

The steady growth in unsecured credit has begun to raise eyebrows in the financial sector. According to the National Credit Regulator’s most recent consumer credit market report, unsecured credit transactions rose by 57.13% between 2010 and 2011, reaching R26.45-billion. From the third quarter to the fourth quarter of last year, it increased by 24.69%.

The unsecured credit market is a growth area for South African banks. Because these loans are deemed riskier, banks are allowed to charge more interest, although they are capped at 32% under the National Credit Act.

Ratings services agency Standard and Poor’s recently pointed out that looming international regulation in the form of the Basel III banking accords and lower credit take-up from South Africa’s cash-rich corporates mean that South African banks are seeking growth in the unsecured credit market.

Unsecured credit

How worried should we be? According to Darrel Beghin, manager for credit information and research at the National Credit Regulator, that all depends on how the credit is being used. Unsecured credit forms about 8% of all lending by South Africa’s banks.

“It is early days yet, but we are watching it,” she said.

The rate of unsecured credit growth is what appears to be causing alarm. It outstrips the growth of mortgage lending, which rose a mere 9% year on year. Meanwhile, as a share of all bank lending, or the gross debtors book, mortgages only rose by 4% between 2010 and 2011.

The real question is whether people are using unsecured credit for productive purposes, such as reinvesting in their homes, or for consumption, such as buying clothes or food.

Unsecured credit transactions are distinct from other kinds of credit, which include mortgages or home loans, secured credit such as vehicle loans, credit facilities such as store cards and short-term credit or loans of less than R8000, repayable within six months.

Current trends indicate a range of reasons why consumers are taking up unsecured credit.

Paying for consumption

For a start, banks had been more cautious with long-term loans, Beghin said. With banks less willing to extend 100% mortgages, for example, consumers were opting to borrow the difference through unsecured loans.

Loan consolidation is another factor as borrowers bundle their outstanding obligations into a single personal loan with more favourable repayment terms.

A third trend involves consumers taking on unsecured credit to pay for building and renovations. It was particularly prevalent in townships, Beghin said, where a lack of title deeds meant people could not access mortgages.

Unsecured borrowing to pay for consumption or “everything from food to clothes” is another, more worrying, trend. People are also borrowing unsecured credit to pay for education, furniture, vehicles and “other” expenditure such as for weddings or funerals.

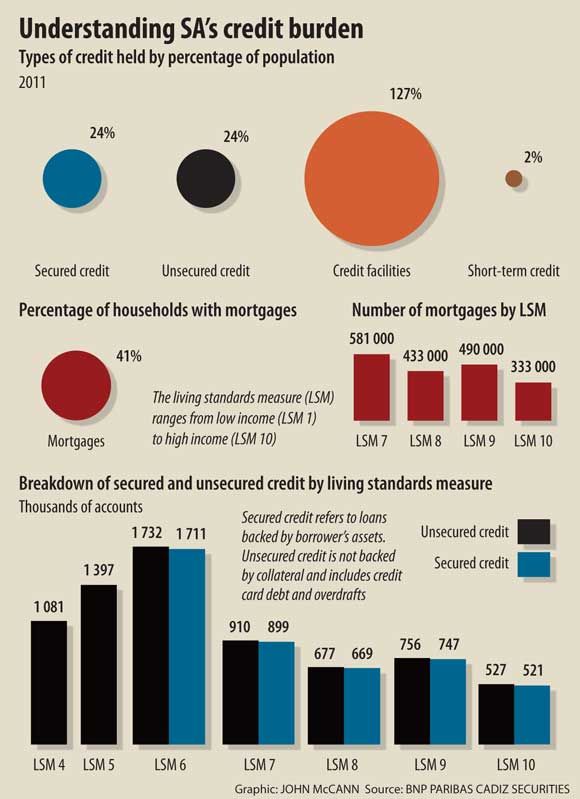

Research released last week by Shamil Ismail, senior research analyst at BNP Paribas Cadiz Securities, indicated that households in lower-income brackets held more unsecured credit accounts. Ismail’s research compared the number of unsecured accounts with the living standards measure (LSM) of households. The measure, developed by the South African Advertising Research Foundation, segments people according to their living standards. LSM 1 is the lowest measure and LSM 10 the highest.

Measure brackets

The report findings suggest that households in LSM 4 hold an estimated one million unsecured accounts, whereas LSMs 5 and 6 hold 1.4-million and 1.7-million respectively.

Households in LSM 4 have an average monthly income of R2797 and those in LSM 5 and 6 have incomes of R3839 and R5991, respectively.

Based on the population sizes of various measure groups, the research found that higher measure brackets, namely 7 to 10, have more credit accounts on average, estimated at 5.1 per household. These include mortgages, secured credit such a vehicle loans, credit facilities such as store cards and short-term loans, typically less than R8000 with repayment terms of less than six months.

According to Ismail, unsecured credit growth came predominantly from medium-term products – or loans with repayment terms of between three to five years. The average value of unsecured loans in this category increased from R20000 in March 2008 to R37000 by the end of last year. This might increase the risk of a “mismatch between consumption period and the loan repayment period”, said Ismail.

“As an example, some consumers may be taking out a R10000 loan and spend it on consumables such as food, living and expenses but have to repay it over five years. This can lead to a build-up of debt,” he said.

Growth of credit-active consumers

Anecdotal evidence suggests that people are using unsecured credit to pay for things such as school fees, second-hand cars, home alterations and deposits on new homes, according to Ismail.

Equally worrying is the growth of credit-active consumers as measured against the South African labour force. The research found that there were 5.8-million more credit-active consumers than people formally employed in South Africa.

Ismail warned that the average number of accounts for consumers in good standing – or those meeting their repayment requirements – had risen from 3.8 accounts per household in 2007 to 4.9 in December 2011.

“We believe this could put pressure on the good-standing consumers and they run the risk of becoming over-extended in debt,” he said.

The National Credit Regulator’s credit market report also revealed interesting trends about the uptake of unsecured credit by individuals. It suggested that more unsecured credit agreements were being extended to people with lower incomes. In the fourth quarter of last year, just less than 64% of the total number of agreements granted went to people earning R10000 or less.

Rand values

In terms of the rand values of all the agreements granted, people earning below R10 000 only held a 41.86% share of the credit granted.

People with an income of more than R15 000 held a 36.79% share of the unsecured credit granted. In terms of the number of accounts issued, however, they only held a 20.52% share.

For the time being, though, the regulator’s research indicates that more than 73.8% of unsecured credit, in rand terms, is reported as current.

Despite the attention it is receiving, the banking sector is not developing an unsecured lending bubble, according to the South African Reserve Bank.

“Although certain categories of unsecured lending are showing high growth rates, the total unsecured credit exposure of banks remains at less than 10% of banks’ total gross credit exposure,” it said in its financial stability review released in March.

“At these levels, unsecured lending does not constitute a bubble and the bank will continue to monitor developments closely.”

The view from Capitec

Capitec Bank has made a name for itself in what is becoming the increasingly competitive unsecured credit market space.

One positive aspect of the growth in unsecured credit lending is that South Africans who traditionally did not have access to formal credit avenues can now access banking services.

Like the South African Reserve Bank, Capitec is confident that unsecured lending is not a threat while prudent lending practices prevail.

“Our credit client range is a good representation of the demographics of South Africa,” said Charl Nel, head of strategic communications at Capitec.

The average unsecured loan size has risen from R2309 in 2009 to R4172 in 2012, whereas arrears have dropped from 10.1% in 2009 to 5.1% in 2012.

Capitec asks its customers to give an indication of why they need a loan, according to Nel.

The most common reasons are home improvements, education, emergencies such as funerals, medical matters, car problems or broken household appliances, and general consumption.

Nel said Capitec did not believe concern was warranted over the discrepancy between formally employed people and credit-active consumers.

“The number of accounts is greater than the number of employed people,” he said.

“This is due to the fact that some people have more than one unsecured credit account [credit cards, store cards and so forth].

“All credit providers have to be sure of an income stream before they extend credit to make sure that they will receive payment on the credit provided.

“We apply the same principles in our business,” he said. – Lynley Donnelly