About 350 private doctors have told the health department that they would like to sign contracts to work part-time at rural public health facilities in National Health Insurance (NHI) pilot sites, according to the department of health's director general, Precious Matsoso. She said most of them would start work in May.

"We have had overwhelming interest, but will first ensure that the clinics where such doctors will be employed are fully equipped and have passed our readiness assessment tests," said Matsoso.

The doctors are to attend health department workshops later this month and in early May to familiarise them with NHI "quality control, payment and monitoring systems".

The physicians will mostly work for government facilities in the mornings "as that is when their private practices are less busy and public hospitals and clinics are overcrowded", said Matsoso.

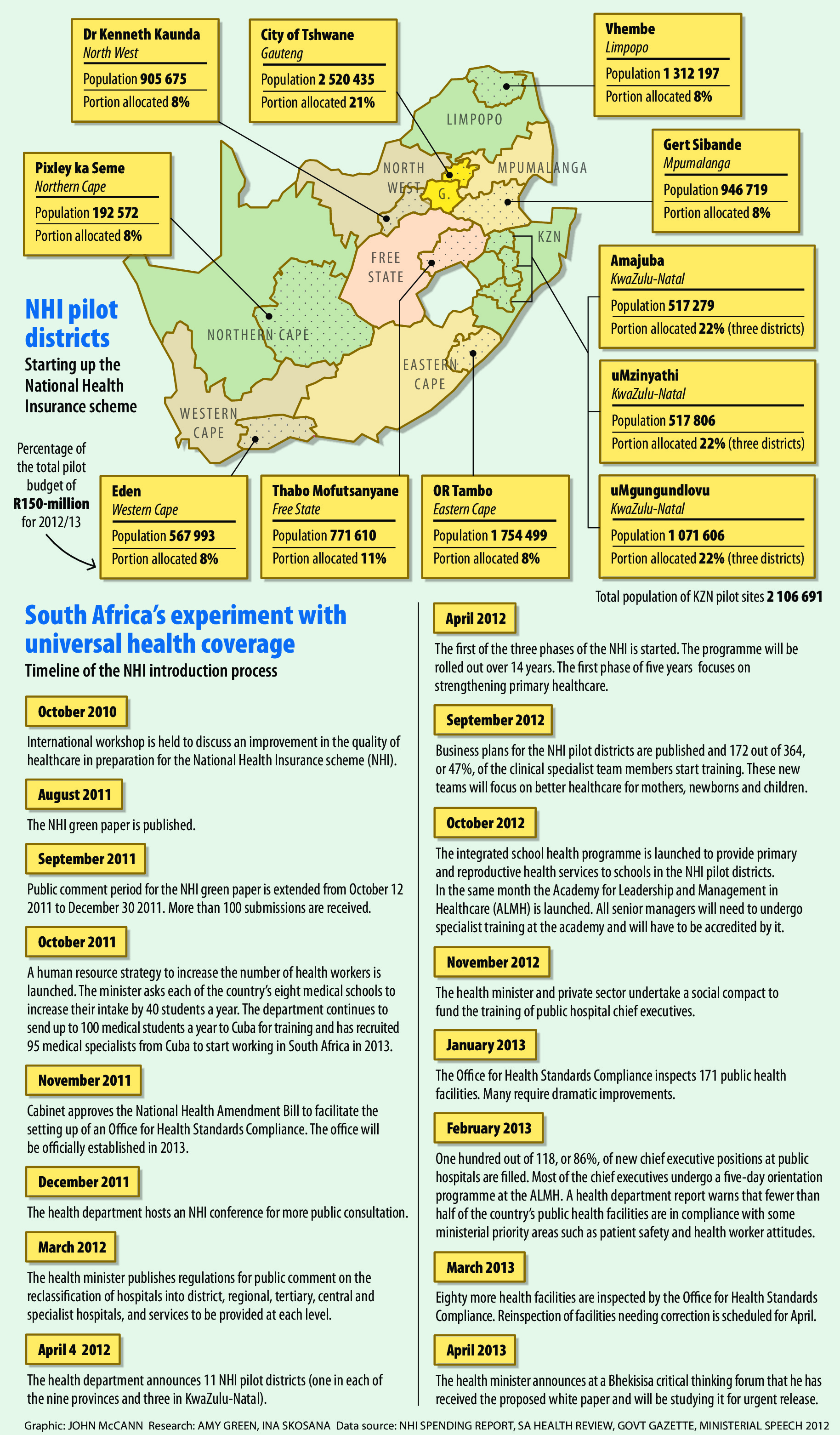

The workshops will be presented in collaboration with experts from the United Kingdom's National Health Service, a system similar to South Africa's NHI. In April last year, the health department announced 11 NHI pilot sites in rural or semirural areas: one in each of the nine provinces, but three in KwaZulu-Natal. The NHI, which is to be phased in over the next 14 years, is intended to provide free access to healthcare to all South Africans, regardless of their income levels.

According to Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi, the country has a drastic shortage of public sector doctors and therefore needs the help of private doctors to implement the scheme successfully.

Matsoso said the treasury had allocated R239-million to contract 250 doctors over the next financial year, but the department also had access to "development aid funds" that would enable it to contract about 600 doctors.

They would be paid by the national health department and not by the respective provincial departments. "This is a first," said Matsoso. "We're doing it to ensure that they receive their salaries on time, as there have been numerous problems with provincial payment systems in the past."

Doctors forced to work from state clinics

The doctors will, however, have to travel to government health facilities to treat patients and will not be permitted to serve state patients from their own private practices.

"The ideal is for state patients to be able to go directly to general practitioners' surgeries, particularly when they are closer to them than government facilities, but South Africa is still miles away from that," said Motsoaledi.

The minister was referring to the incidence of private doctors claiming for work hours in public health facilities when they had, in fact, been absent from work or claiming for significantly more hours than they had actually worked.

According to Meshack Mbokota of the South African Medical Association, private doctors under the NHI will be forced to work from state clinics until the government has "proper" monitoring systems in place to ensure that doctors claim "only for actual hours worked".

But, Mbokota emphasised, "in these cases, doctors need to be reimbursed not only for their professional services, but also for the overhead costs at their private practices that continued to accumulate when they worked at state clinics.

"Private doctors will continue to practise in the country only when they are able to make a reasonable profit and the government needs to take that into consideration," he said. Several cost studies had been conducted so that the "running costs" of practices in different areas could be determined.

He said the health department currently used a "nonaccommodating session system", which reimbursed private doctors who assisted in the public health sector at fixed hourly rates, regardless of the area in which they worked or how far they travelled to clinics.

"A session normally consists of 20 hours a week, or four hours a day, and it is not possible to be contracted for a longer or shorter period, which makes it an extremely rigid system. The rates also do not take doctors' overheads into consideration."

A document circulated to personnel by the Gauteng health department last year stated that a private doctor working part-time as a state medical officer was paid between R251 and R333 an hour, depending on the doctor's level of experience. Most medical schemes reimburse GPs at those rates for a 15 to 20-minute consultation.

'Fee for service' vs 'capitation'

Matsoso said that although the payment methods for doctors employed at NHI pilot sites had not been finalised, they would differ from current systems and use a combination of "fee for service" (the current method of payment in the private sector) and "capitation" (a fixed rate based on the potential number of patients a doctor sees) remuneration systems. "We will be using a global value model that combines these methods, because we have realised that none of the current methods are ideal," she said.

According to Matsoso, the new payment methods will also reimburse doctors for their travel costs and, in some cases, for accommodation if they have to sleep over to spend more than one day at a specific public health facility.

"We're considering models whereby private doctors who are able to do so, for instance, spend an entire week at a time at a hospital or clinic," she said.

Matsoso said that although the department would not like to implement a "classroom system of signing in and out" to ensure that private doctors adhered to work hours, the NHI clinics would use a stricter system that would be require GPs to have regular meetings with clinical and district managers "during which they will have to update them on cases seen, share case histories and help with forward planning, all duties that will be extremely challenging to carry out if you haven't been working".

Other methods the government is piloting to contain doctors' fees include a case-based hospital payment system known as "diagnosis-related groups", which specifies standard costs for certain procedures, such as the removal of an appendix, as opposed to the "splitting up" of the operation into different smaller procedures for which a doctor can charge separately. The diagnosis-related groups system is being piloted in several hospitals, including Universitas Hospital in the Free State, Steven Biko Hospital in Gauteng and Inkosi Albert Luthuli Hospital in KwaZulu-Natal.

According to medical administrator Medscheme's chief executive, Andre Meyer, there are more GP practices in South Africa than clinics and community health centres.

"For a rural person, the NHI would seem more tangible if she or he could go to the closest GP and not have to pay, without having to travel long distances to get to a clinic."

Mbokota agreed: "In my experience, public hospital lines did not become significantly shorter when I worked in the facility.

"However, when I started seeing patients in my own surgery next door, I started to see the pressure being taken off the public facility. But we have to realise that we are not there yet.

"The NHI is still in the first stage of labour. It is a painful process. Eventually the baby will be born and be happy, but it is going to take time."

Next week, we will focus on the opportunities and challenges relating to the involvement of medical administrators in the NHI.