General Richard Mdluli appears to be a dangerous man. The suspended crime intelligence boss, it will be remembered, is accused of abusing his position at the apex of one arm of the "secret state" to acquire and dispense personal benefit and political favour.

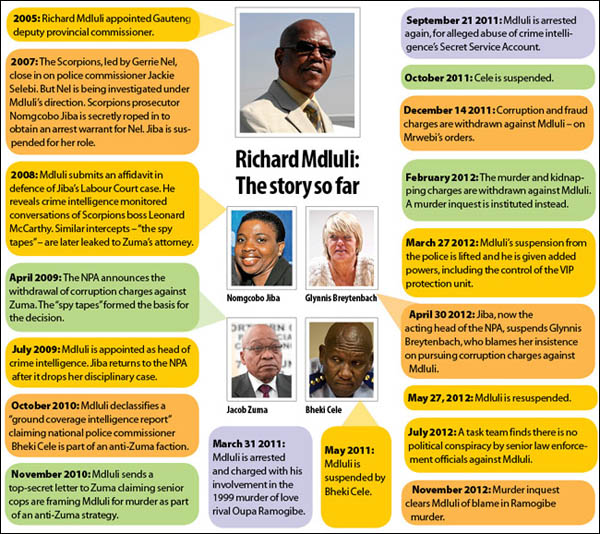

Mdluli allegedly had discounts due to the Secret Services Account transferred for his own advantage, presided over the appointment or promotion of friends and family as covert agents, and wrote to President Jacob Zuma, making allegations of political plots and offering a pledge of loyalty.

Nor should one forget the unresolved 1999 murder of his one-time love rival, Oupa Ramogibe, or the untested evidence of Mdluli's involvement in threats against Ramogibe's family and associates.

But the court battle finally beginning next week in the North Gauteng High Court in Pretoria is about much more than Mdluli's future. It also highlights a much wider danger than whether he returns to control one of the peaks of covert state power.

Next Wednesday, the nongovernment watchdog Freedom Under Law will attempt to have the courts step in to enforce accountability in one of the most profound tests of our constitutional architecture.

The watchdog is asking the court to order the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) to reinstate corruption and murder charges against Mdluli and to order the national police commissioner to reinstate disciplinary charges against him.

The state exercises its coercive power mainly through the police and prosecutions system, which is why the checks and balances on these institutions are so important, and why the individuals wielding executive authority in these areas must be beyond reproach.

The separation-of-powers doctrine suggests that the executive, the judiciary and the legislature must be careful not to stray into each other's domains, which means that the courts will not easily substitute their own decisions for those who are duly authorised to make those decisions, such as prosecutors and police commissioners.

But that deference depends on two caveats: such decisions should not be subject to undue pressure, and decision-makers must, when required, be prepared to justify the decision in significant detail.

The discipline of justification is the core of the constitutional framework, of the very power of the courts. Without it, the Constitution is merely a set of ideals.

And it is not easy. The discipline of justification imposes a significant, if necessary, bureaucratic burden.

It requires the state to keep good records; it requires officials to know, understand and have regard for the changing landscape of laws and regulations that govern their conduct; and it requires that officials demonstrate this when legally called upon to do so, including disclosing all records relevant to that decision.

Resistance to the culture of justification is understandable – and not only when officials are trying to cover up wrongdoing. If the bureaucracy degrades, if the state begins to fail, officials find it harder to resist challenges to doing good things as well, such as going after tax cheats or deporting foreign criminals.

The courts face a tough choice: lower the bar for the state, or uphold constitutional obligations that may embarrass the state and add significant strain to the tension between the executive and the judiciary.

The Mdluli case is an important test of judicial resolve: almost a dry run for the Democratic Alliance bid to have the courts review the decision to withdraw corruption charges against Zuma.

It should be recalled that the Zuma administration set the scene for this showdown with a series of politicised appointments, including those of Mdluli himself, of the acting national director of public prosecutions, advocate Nomgcobo Jiba, and of the head of the Specialised Commercial Crime Unit, advocate Lawrence Mrwebi, the man who ordered the prosecution of Mdluli on corruption charges to be withdrawn. And then, the acting-commissioner, Lieutenant-General Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi, dropped disciplinary proceedings and reinstated Mdluli in March 2011 after a meeting with Police Minister Nathi Mthethwa.

He later attributed this decision to authorities "beyond" him.

So it is hardly surprising that both the NPA and the police are now resisting Freedom Under Law's efforts to have a court second-guess decisions about Mdluli.

Both have resisted supplying a full record to back up those decisions and both are seeking to claim that the ambit of the review is beyond the high court's jurisdiction.

Rather than dealing with serious questions about Mdluli's fitness for high office, national commissioner Riah Phiyega has argued in her court papers that the disciplinary process against Mdluli is an employment issue that must be left to her.

Freedom Under Law chair and former Constitutional Court judge Johann Kriegler, in his replying affidavit, lashed out at this approach.

"To the extent that the court is asked to decide anything 'without facts', that lack of facts is directly attributable to the failure of the national commissioner to file a complete record of proceedings … to her abject failure to take the court into her confidence about those facts …

"It is, with respect, a matter for serious concern that the national commissioner can characterise public alarm at charges of murder and associated criminality against a key police general as 'a fuss'.

"A labour dispute exists only between employer and employee. This matter is a dispute between a government entity and the citizens to whom that government is accountable, which affects the security and stability of the republic."

Kriegler also batted away suggestions by Mrwebi that the watchdog was intruding on prosecutorial decisions.

"I wish to endorse the assertion that, in the ordinary course, there is 'no basis whatsoever for this honourable court to enter the terrain of the NDPP [national director of public prosecutions]'. Sadly, however, this is most decidedly not an ordinary case. On the contrary, the circumstances were from the outset extraordinary and have become more so as the case has progressed."

It remains to be seen whether the courts – and the matter will undoubtedly go up the chain to the Constitutional Court – are willing to grasp the nettle that Freedom Under Law has placed in front of them.

* Got a tip-off for us about this story? Email [email protected]

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism (amaBhungane) produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for our stories, activities and funding sources.