BaD Tour guides Mike Silva

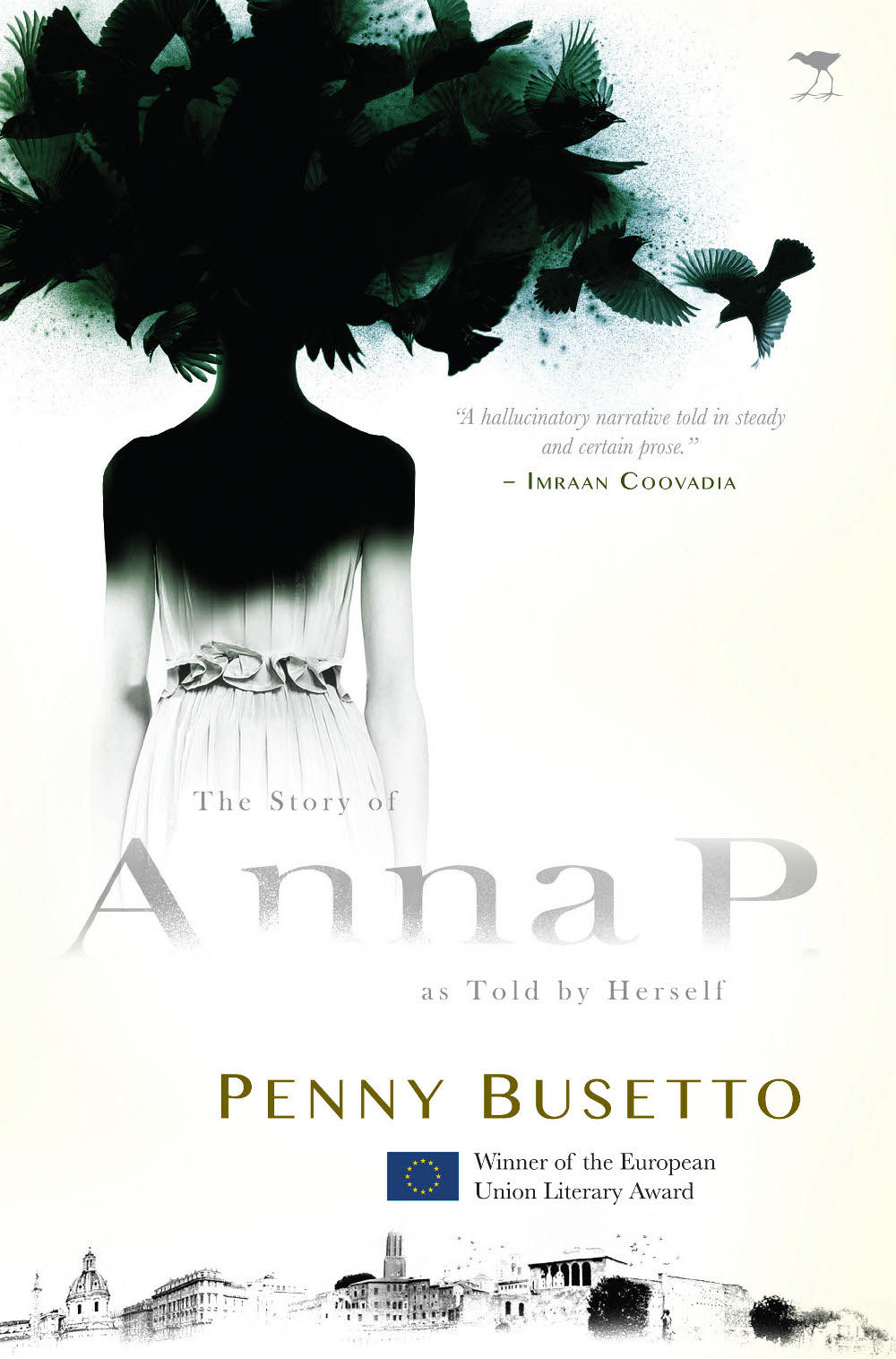

Penny Busetto's debut novel, The Story of Anna P as Told by Herself (Jacana), the winner of the European Union Literary Award 2013, investigates the nature of memory and the importance of identity. Busetto answers the Mail & Guardian's questions about her book:

Describe yourself in a sentence.

I find it very difficult to describe myself – I feel as if I am constantly shifting and transforming and contradicting myself, so that as soon as I think I have captured some aspect of who I am, I immediately become aware that its opposite is also true.

Describe your ideal reader.

My ideal reader is someone who can tolerate, or even appreciate, the ambiguities in my writing; someone who will bring their own subjectivity to the reading and allow themselves to be moved by the feelings of loss and despair and wonder.

What was the originating idea for The Story of Anna P?

I began to write this book while reading Antjie Krog's Country of My Skull, her account of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In it she quotes Zalaquett, the human rights lawyer, as saying: "Identity is memory." I remember being deeply struck by these words. For months afterwards I couldn't get them out of my head, and found myself writing them all over the place, doodling them while my mind was occupied with other tasks, including them in paintings.

I could never remember whether it should be "memory is identity" or "identity is memory", or whether that even made any difference. I began to wonder what identity was and, if it was identical to memory, whether there was any possibility of ever moving beyond memory, beyond the past. And if our identity is trapped by what happened in the past, what hope is there for humanity, for South Africa with its traumatic past?

These felt like very important questions to be asking as a South African writer. I began to write the story of a woman, Anna P, whose actions are dominated by her unconscious memories of a traumatic past. I chose to call her Anna P, like Anna O – who suffered from hysterical mutism following trauma – in Freud and Breuer's seminal case study.

Were the years you spent in Italy significant?

My time in Italy, where I studied and lived for many years, was very significant for me – it opened up intellectual and cultural vistas that probably would not have been possible to me if I had stayed in South Africa.

In 1970 South Africa was very remote from Italy – a letter took two weeks, telephone calls had to be booked days in advance through an exchange at the post office, and there was absolutely no news of South Africa in the newspapers, and hardly anyone in Italy, at least in the provincial towns where I first lived, spoke English. I was fortunate to be able to study there and marry into a sophisticated, politically engaged, intellectual Italian family who welcomed me into their midst.

They gave me the tools to make sense of what was happening around me as well as the historical depth and memory that I could not have as a foreigner.

On a deeper emotional level, I found that there could be a different breath, a different rhythm, to my life in Italy.

While South Africa had felt jagged, fractured, traumatic, with no sense of a way out, in Italy the layers of history, the sense of the past, of continuity in spite of death and destruction, the cyclical return of the seasons and their colours and fruits, brought softness and healing.

It felt like a slow, horizontal, wavelike rhythm, to contrast with the vertical, harsh rhythms of my country of origin. I believe that the jagged vertical and slow horizontal alternate in my book and make each other possible.

Describe the process of writing the work. How long did it take?

It took me three or four years to write the book, and I never knew, until the end, how it was going to turn out. It seemed that the process was not under my control – I could not will the work forward.

It came through the writing. The only way I could will it was through the discipline of writing a certain number of words every day.

I try to write 2 500 words a day. It sounds like a lot, I know, but I find that it is not difficult once I have established a routine.

A lot of what I write is repetitive or bad, but it allows me to play and not get too frantic about not getting anything done.

I don't correct what I am doing as I write it, I don't go back. If a passage doesn't satisfy me I will write it again, anew, and will keep doing that until I feel satisfied, rather than reworking something unsatisfactory.

Name some writers who have inspired you and tell us briefly why or how.

I can feel many influences running through my work, some more obvious such as the Bible, and Dante and Shakespeare and, of course, Augustine, Rousseau, Dostoevsky, Eliot and Kafka. But also the elegiac qualities of Ovid, Pessoa, Pavese, Malouf.

Do you write by hand?

I write by hand in A4 counter books, which I label according to month and year. Some months I fill three or four books, sometimes the book carries over to the following month because I have barely written anything. I write with disposable fountain pens – I like the soft resistance of the nib on the cheap paper.

What is the purpose of fiction?

Fiction opens new ways of experiencing feelings that are caught in the concrete details of our lives. Writer and reader are opened to potentials they did not know they had the ability or the capacity to experience.