The material for the conservation project comprises a fascinating collection of notes

African art historians and critics have been preoccupied with modernism in African art, but there appears to be a misguided idea about the difference between processes of modernity and colonialism.

Curator Khwezi Gule believes the popular sentiment that the extent to which Africans have sought to confront some of these processes affirms that modernity is not just a European construct.

It’s been suggested that Spanish artist Pablo Picasso denied the influential role African masks played in his art. His reason: he had never visited Africa.

However speculative, the late art critic Colin Richards said the suggestion should make us wary about which cultural concepts are made useful and which are not; to steer clear from the “notoriously fickle line between self-affirmation and denial of the ‘other'”.

It’s particularly important to keep a healthy balance when institutions embark on a collaborative cultural project.

Restoration support

Merrill Lynch Bank of America recently announced that the Rock Art Research Institute, located at the Origins Centre at the University of Witwatersrand, will receive support to restore and conserve material from the late South African artist Walter Battiss. The material was donated by his son, Giles Battiss, a few years ago.

In 2010, Merrill Lynch embarked on an art conservation project to provide grants for non-profit-making museums and cultural institutions in various parts of the world. Since then, the bank has supported 72 projects in 27 countries.

The focus of the conservation project is to provide funds and support these institutions with the restoration and conservation of historically and culturally significant works of art. This includes a $50?000 conservation grant, through Merrill Lynch’s 2014 global art conservation project, to the Society of Antiquaries of London for the restoration of two copies of the Magna Carta dating back at least 800 years.

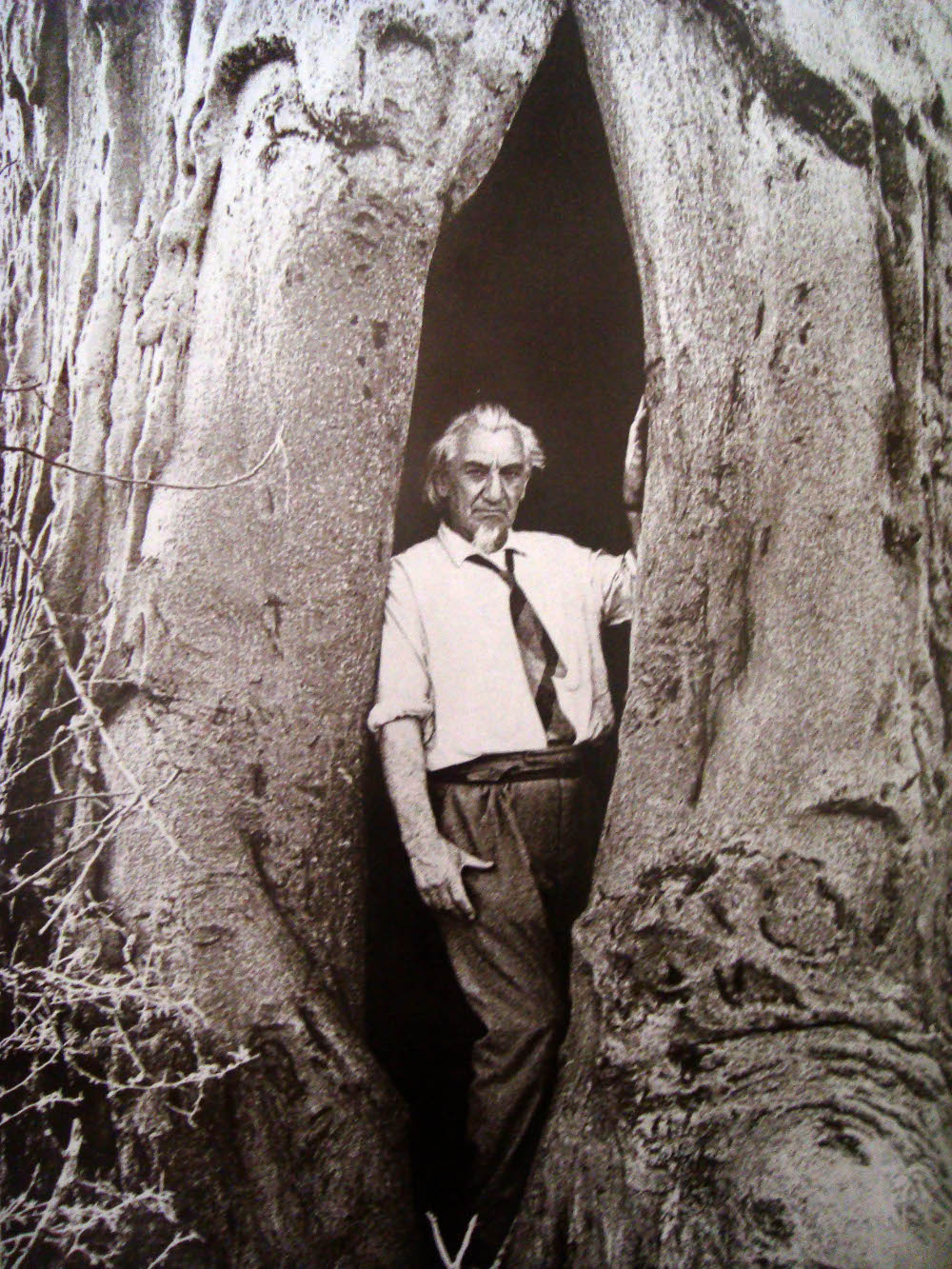

Artist Walter Battiss.

In South Africa, this grant has been received by the Wits Art Museum (WAM) to conserve a collection of Ndebele beaded aprons and by the Johannesburg Art Gallery to conserve 10 paintings by renowned artist Gerard Sekoto. The paintings formed part of his exhibition A Song for Sekoto held at WAM in 2013.

The Battiss conservation project not only connects a unique blend of different fields such as art, archaeology and history but also reveals a somewhat lesser-known facet of Battiss’s work. The material comprises a fascinating collection of notes, diary entries and drawings of important local archaeology sites that Battiss visited in the early 1940s and 1950s.

Lyrical paintings

Born in Somerset East, Battiss is widely known for his lyrical paintings and the creation of Fook Island, which was born shortly after visits to a number of islands, including the Seychelles, Zanzibar and Hawaii.

Fook Island became an allegory of the unorthodox, dismantling all kinds of conventions related to citizenry, censorship, language and the exotic. It did not only become a way of life for Battiss but also one he employed to navigate the murky waters of life under the apartheid regime.

Battiss spent part of his childhood in the rural Free State, a place that would later shape the style of art he produced as his interest in archaeology grew.

After spending some time living among the Khoisan in the late 1940s, he published two books on rock art, titled Artists of the Rocks (1948) and Bushman Art (1950s).

It is during this time that he is believed to have met Picasso and other well-known artists.

This art conservation project creates an invigorating prospect for a new archaeological exercise, an excavation of sorts uncovering Battiss’s mind, but more importantly one that gives clues to our intriguing past and how we all connect.

Significant research contribution

According to David Pearce, director of the Rock Art Research Institute at Wits, the project presents two major components that will contribute significantly to archaeological studies in rock art research.

The first is the contribution it will make to the history of archaeology and developments in the field.

These developments are driven by technological advancements as well as other innovations through interdisciplinary approaches that incorporate science and history. They include processes such as digitisation, which presents new possibilities and challenges for the Rock Art Research Institute.

A Walter Battiss drawing from an archeology site.

The digitising programme enables researchers and historians to engage and interact with material that deteriorates and would be too fragile to handle.

One of the drawbacks of digitisation is concern over what and who determines what is historically or culturally significant to conserve, so somebody subjectively decides what is kept for public memory versus what gets obliterated and forgotten in the archives.

The second component surrounds what happens after the restoration. Battiss made diagrams and drawings of sites but many of these sites have since disappeared or deteriorated because of natural causes such as climate change. The conservation project will allow scholars and researchers the opportunity to return to these sites and hopefully reconstruct what was lost over time.

Educational programme

Once complete, the project will also integrate an educational programme aimed at reaching communities that do not have access to such institutions. In fact, part of the application for the grant requires that institutions clearly show how the grant will assist them in making a contribution towards community development and fostering better understanding among different cultures.

Given the lack of conservation skills in the country, the educational programme will form a critical way to measure the success of the project, in both how the material is compiled and narrated to audiences.

The real challenge for these institutions, then, is to strike a balance in how knowledge is disseminated, so that as we move into the age of the fight for economic emancipation, we remain cognizant of who creates cultural capital and the value it adds to economic development.