People who use creams to lighten their skin risk causing lasting damage to their bodies and nervous systems.

Lucky Shezi’s house is small and crammed. “I try to keep my house clean, but it really needs the touch of a woman,” he says.

Frustrated, he puts his gym bag down on the bare floor of his home in Phoenix, northwest of Durban in KwaZulu-Natal, and sits on one of the flowery couches. At 49, Shezi believes that a change in his grooming habits will help him in his long arduous search for love. Last year he started using a skin-lightening cream he had read about on the internet.

“I started using the cream because I just want to look smart and handsome. It wasn’t about me having a light skin; I naturally have chocolate skin. I am not so pitch black.”

He says that there hasn’t been a drastic change in his skin colour. He is aware that there are problems linked to skin-lightening products, so he uses the cream sparingly. “But I can see an improvement when I look at myself in the mirror,” he says with a self-assured nod. “I’m looking handsome.”

And his female colleagues have noticed a change. “At some stage they kept asking me what I was using. They said I was changing …though they didn’t say in as many words that I was handsome or anything. This means that my cream must be working.”

Desire to improve appearance

Lester Davids, a senior lecturer in human biology at the University of Cape Town (UCT), says the main reason people like Shezi use skin-lightening products is their desire to improve their appearance. “People often use skin lighteners because they want to look prettier. There is a perception that white or light skin is more attractive and that is the unfortunate aspect of the psychosocial issues relating to skin lighteners.”

Men like Shezi, who are willing to admit to using skin-lightening products, are an anomaly. But Davids, who has done extensive research into the use of skin-lightening creams among women, believes the number of men using the products will increase.

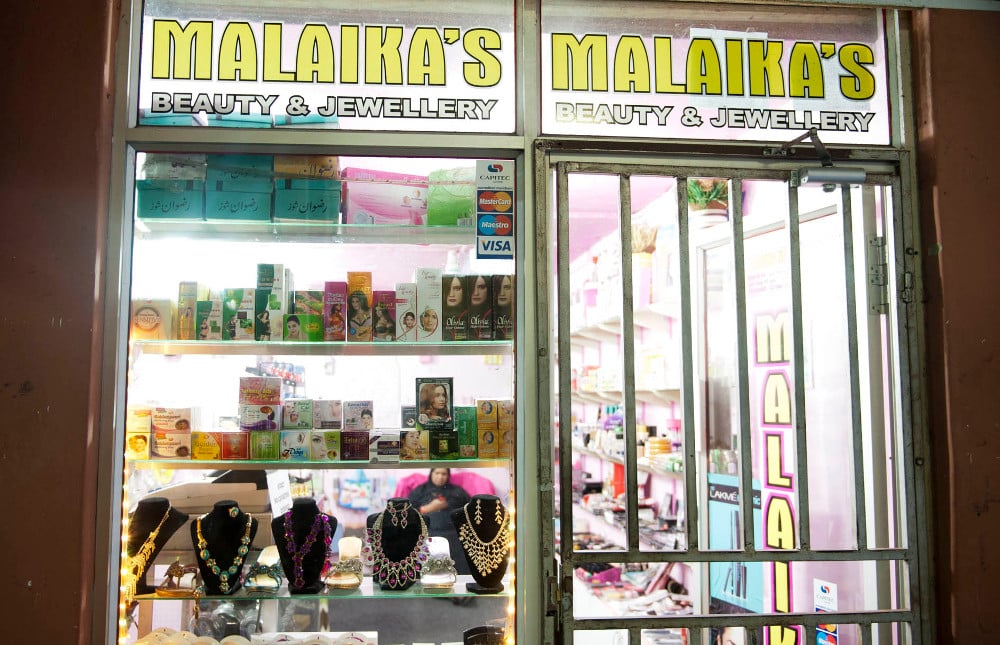

Davids warns that the demand for skin-lightening products has led to a surge in the availability of “unsolicited, untested” products on the market. “Very often the good products are out of the price range of the majority of the people, with the result that many people are going to be looking for cheaper products.

“These cheaper products are unsolicited, untested and have hit the market at a staggering rate. This is going to lead to, frighteningly, an increase in skin damage, or potential skin damage.”

Health risks

Nonhlanhla Khumalo, a dermatologist and a colleague of Davids, says the real extent of skin lightening in South Africa is unknown, but research suggests that 35% of women use these products regularly.

As part of the multidisciplinary study at UCT, a survey was conducted to identify popular skin-lightening brands. Researchers identified 29, one of which Shezi uses.

“We bought most of these from informal vendors and at Cape Town station and did detailed laboratory analysis to identify the active ingredients,” says Khumalo. “The main ingredients are what we suspected: hydroquinone and prescription-strength topical steroids.”

Khumalo says, although skin lightening does work, “the initial whitening does not last long as the skin becomes permanently damaged” by the active ingredients in some of the products.

These ingredients, she says, pose a number of health risks. For example, topical steroids such as betamethasone and clobetasol can lead to a range of complications that include “red thin skin, prominent blood vessels, increased hair [on the forehead and cheeks], pimples and brown marks”. Betamethasone relieves pain, swelling and itching but is a corticosteroid that carries a risk of side effects. Clobetasol is also a corticosteroid and is used to treat serious skin disorders such as eczema and psoriasis.

Banned substances

Davids says: “Hydroquinone has been banned by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States. In South Africa hydroquinone is only allowed to be used if prescribed clinically. Even then it cannot be used by more than 2% within a formulation.”

Hydroquinone constrains the formation of melanin or skin colour and “over the short term works very well as a pigment inhibitor”. It is used for a condition such as vitiligo, which causes a loss of skin colour or pigment, resulting in irregular white patches.

“Michael Jackson had it, for example,” says Davids. “A vitiligo patient wants to de-pigment or to remove the pigment off the rest of the body if they’re suffering from 80% vitiligo. So as the condition spreads, dermatologically you may want to offer the patient the option to remove the rest of the coloured areas.”

Another common ingredient is retinoid, a chemical compound related to Vitamin A, which is used as a cure-all for a number of problems. “They work very well, but with long-term chronic and high concentration use, they not only cause damage to the skin but to organs as well,” says Davids.

An unexpected finding of the laboratory tests conducted on lightening creams was the “frequent and high concentrations of mercury”, says Khumalo.

Mercury lightens the skin by preventing the production of melanin, which determines skin colour and provides some protection from the sun. “It gets absorbed and can cause damage to the nervous system. That is why it is completely illegal in cosmetics in South Africa and many other countries,” says Khumalo.

“Lack of effective regulation”

But not all skin-lightening products are illegal. Davids says the problem is the lack of effective regulation of cosmetic products in South Africa.

“If I wanted to sell a clinically or medically related drug, I would have to go through the Medicines Control Council, which will request [a list of]every ingredient that is in the drug and details on how it was tested. All this even before the drug actually comes on to the market.

“Under the Cosmetics Act, that is not necessary. So I can put a cream in a container, put a nice label on it and market it as a cosmetic and it will be available over the counter,” says Davids. “It’s not illegal, but the information regarding what is actually in that formulation is very scarce.”

A 2010 British Medical Journal article calls for the stricter regulation of skin-lightening products, particularly in Africa, because these creams “alter the chemical structure of the skin by inhibiting the synthesis of melanin and should therefore be regulated as drugs – not cosmetics”.

Davids says that in the absence of effective regulation it is up to the consumer to be informed about the long-term effects of these products.

“Don’t forget, you are using the cream now, but you are only going to be seeing the consequences of the chronic and long-term use in about six to eight months’ time,” he warns. “Then you are going to be suffering the effects of a damaged skin and irreversible damage.”

Shezi buys the cream he uses from a number of shops close to where he works in downtown Durban. He believes that because this cream is widely available in shops, it presents no harm to him.

“If this thing is dangerous, doctors would have said a long time ago that it mustn’t be sold in the country. Anyway, I don’t use it every day; only on occasions when I want to spark.”

Bone of contention: Is it self-hatred or redefining oneself?

Do you want a lighter skin or were you born with the wrong skin colour? Well, a Johannesburg-based business owner, Neo Mabita, says that her company, the Yellow Bone Factory, can fix that for you.

“The texture of your skin colour is a currency. If you look a certain way you get a certain reaction from people. What you deem as beautiful or as a ‘yellow bone’ may not necessarily be what somebody else views as such.”

The term yellow bone is used to describe a light-skinned black person, and is considered offensive by some. But Mabita says perceptions of what a yellow bone is are subjective and differ from one person to the next.

“The skin-lightening business is what started the Yellow Bone Factory, but the Yellow Bone Factory is about more than just skin lightening. We’re more about helping women redefine themselves.”

According to a 2010 British Medical Journal article, skin lightening or bleaching, which is common among black Africans, “is fuelled by racial prejudice [and] stems from the misconceptions that black skin is inferior and someone with fair skin is more attractive”.

The article attributes the “habit of bleaching” to a number of factors such as the prominence of light-skinned women in the media and celebrities who also bleach their skin. This perpetuates the idea that white or light-skinned people are more successful and desirable, the article states.

In South Africa, kwaito singer Nomasonto Maswanganyi, also known as Mshoza, made headlines when she made the choice to bleach her skin. Actress and former Miss India South Africa, Sorisha Naidoo, bleached her skin a few years ago and now owns a range of skin-lightening products.

The practice of skin lightening has been criticised as being unAfrican and a form of self-hatred. “Race is a socially constructed thing that people use to label one another,” Mabita hits back. “At what point do you draw the line of what people can do to better themselves? At what point do we say this skin colour belongs to this race?

“African women are the biggest contradiction. No African woman who is wearing a weave is going to tell me that they’ve got issues with skin lightening.”

The 31-year-old from Soweto, who uses skin-lightening products “to maintain her natural complexion”, says the practice doesn’t translate into a change in one’s racial profile or status.

“I think that self-hate stems from a lot of things, like racism, and not primarily skin colour. Why can’t we fix ourselves to make ourselves presentable to the world the way that we want? Why is that called hating yourself? I do not think skin lightening has got anything to do with self-hatred. In fact, I think it’s an appreciation of one’s self. It’s realising that you can morph yourself into anything that you want and still remain who you are.”

People who say skin lightening is self-hatred or “unblack” need to “reinvestigate what blackness is”, says Mabita.

Shop for safe products

Many people are using low-end, unsafe skin-lightening creams because they are cheaper than products that have been tested. Lester Davids, a lead researcher in a multidisciplinary study at the University of Cape Town, warns that the exact ingredients of many cheaper skin-lightening creams are unknown and not usually listed on the packaging.

Products that are safe “will be supplied with an insert that will have all the ingredients listed, and will have all of the bases of use and will have instructions on how to use them”.

“Those instructions [are not available] with the cheaper creams that you will get at a station market or that you can get in an unlabelled bottle or tube at any of the markets anywhere.” Very often the problem lies in the distribution of these products. “By the time it actually hits the shops, the shop owner has absolutely no idea what is in the cream.”

Davids says that there are a few questions one should ask before buying a skin-lightening cream:

What is in this cream?

“This seems like a very obvious question to ask but you’d be shocked and amazed at how few people actually ask it. “When I buy a cream for my skin in a shop, the first thing I look at is: What is actually in this cream? “Most of these creams don’t even have an ingredient label on them.”

Where is the cream from?

“It is important to know who actually supplies the cream. For example, if you want to buy meat, you would want to know who supplies the meat to the shop that you go to, because that relates to the quality of the meat. “In the same way you have the right to ask where this [cream] is supplied from.”

How long has the formulation been in this container?

“Under normal circumstances, any tube that you buy that comes with a little insert will have an expiration date on it, and it will have a date of distribution on it. So you will be able to tell how long the cream has actually been around. “The longer a cream stands, the more oxidised it becomes and these polyphenolics, if there are any in the cream, become more toxic.”

Have these formulations been properly tested?

“I think this is the fundamental question because, when you market products under the Cosmetics Act, half of the stringency and the need for testing that is required for medical or clinical drugs goes out the window. “And so we are quite concerned about the fact that a lot of these creams are hitting the market without being scientifically tested.”

[This story was originally published on 31 October 2014]