Soldiers in Kenya.

Kenya’s war with al-Shabab in neighbouring Somalia entered its fourth year this month, with successes on the battlefront, but increasingly painful and costly spin-offs back home.

Kenya celebrated Kenyan Defence Forces (KDF) Day on October 14, marking the date three years ago when its troops entered Somalia.

As Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta led the nation in a sombre commemoration, he said defending the country and the rest of East Africa had never been more difficult.

At the same event, the country’s military chief, General Julius Karangi, strongly defended the operation, pointing out that al-Shabab had carried out attacks inside Kenya long before the KDF initiative was launched.

After years confined to peacekeeping missions at home and abroad, the KDF initially believed its Somalian assignment would be over in a few months.

But the fight is far from over and there appears to be no clear exit plan.

A turning point in waning popular support for the war was last year’s ruthless Westgate mall siege, in which 67 mainly civilians died.

Light in the dark: A vigil held at the National Museum in Nairobi marked the first anniversary of the Westgate attack (Simon Maina/AFP)

Brutally killed

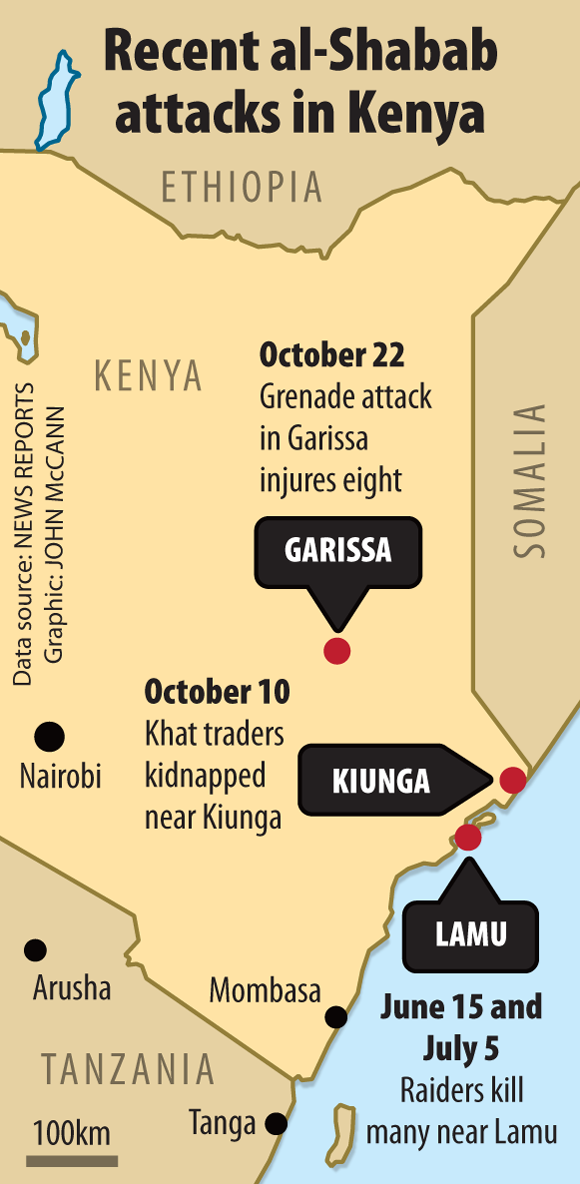

Another less well-known massacre took place in June and July this year in the coastal town of Lamu, when about 100 Kenyans were shot dead or had their throats slit. Al-Shabab singled out men who could not convince them they were Muslim. Since the attack, Lamu, in a popular tourist area on Kenya’s coast, has been placed under a dusk-to-dawn curfew.

Kenya started fighting under the umbrella of the African Union Mission in Somalia (Amisom), a peacekeeping mission of the AU with United Nations backing, in February 2012, five months after crossing the border.

Amisom has more than 20 000 troops and policemen in the field, drawn from nine African countries. But al-Shabab has hit back, punishing the participating nations for sending troops into its backyard.

Kenya, which has committed about 3 600 uniformed personnel, has now replaced Ethiopia as al-Shabab’s prime target. According to Kenya’s anti-terrorism police unit, the country has suffered 133 terror-related attacks – one every eight days – since the offensive began.

Last month five Kenyan khat traders were kidnapped by suspected al-Shabab militiamen on Kenya’s northern coast. Two weeks later, eight people were injured in a grenade attack in the northeastern town of Garissa.

Al-Shabab has regularly warned on social media and in propaganda videos that it will “teach Kenya a lesson” unless it withdraws its forces.

The heightened climate of insecurity among citizens has inflicted serious damage on the country’s tourism industry.

The tourism secretary, Phylis Kandie, recently told journalists that tourism has been in decline since last year, with arrivals dropping 15% in 2013 compared with the previous year. Arrivals through Kenya’s main airports dropped a further 13% in the first half of this year.

Economic decline

Kenya earned R10-billion from the sector last year, making it one of the top three foreign exchange earners in East Africa’s biggest economy. Another consequence has been the shedding of up to 4 000 jobs in the sector, and about 20 coastal hotels have closed.

Terrorists have hit schools, hurled grenades at Christian crusades, blown up police stations and attacked vehicles, hotels and nightclubs. At least 370 people have been killed, including an MP, a pastor and a child sitting on her mother’s lap in church. More than a thousand have been injured.

As more and more Kenyans are affected by violence, the initial support for military action has fallen.

A survey by the research firm Ipsos Kenya, published last month, shows that four out of five want the troops to come home. The poll highlights the fear al-Shabab now provokes among Kenyans – 68% consider the threat it poses extremely high and only 3% consider it no threat at all.

It also underscores the popular confusion about how to respond to the situation. Only 19% want the KDF to stay put, but there are deep divisions over whether it should return only if replaced by other AU forces; continue to protect Kenya’s borders; or be brought back unconditionally.

At the political level, national pride has become the key policy driver. Government leaders say Kenyan forces will not be withdrawn until the “battle is won”.

Kenya’s membership of Amisom, with Uganda, Tanzania, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Nigeria and Burundi, is a complicating factor. According to the Amisom spokesperson, Major Deo Akiiki, Operation Indian Ocean, the anti-terrorism sweep in Somalia, which started in August, could continue after the 2016 Somali elections.

Another poll released last month, by South Africa’s Institute of Security Studies (ISS), suggests that Kenya’s response to terrorism may have aggravated the crisis and that many Muslim youths have joined extremist groups in reaction to the government’s collective punishment of Muslims and assassination of religious leaders.

Police also suspects

Officers of the police anti-terrorism unit have been accused of playing a part in the murder of high-profile clerics such as Sheikh Aboud Rogo in August 2012. His successor, Sheikh Ibrahim Omar, was shot in October last year and Sheikh Abubakar Shariff was killed in April this year.

The Kenyan government had accused the clerics of recruiting youths from the Masjid Musa mosque for al-Shabab, and was prosecuting Rogo and Shariff on related charges.

“It is clear from the research that strategies based on mass arrests and racial profiling are counterproductive and may drive individuals to extremism,” researcher Anneli Botha says in the ISS report. “Unless government changes its approach, there is a real risk it will inspire a new cycle of radicalisation and violence.”

According to 65% of respondents, who included 95 people associated with al-Shabab, 45 associated with the Mombasa Republican Council, a separatist group on the Kenyan coast, and relatives of people associated with both organisations, the government’s counterterrorism strategy is the most important factor driving people to join al-Shabab.

The research indicated that Kenyan Muslims feel discriminated against, and nearly half the al-Shabab respondents identified the government as a threat to their religion.

Most al-Shabab respondents (87%) referred to religion or the need to respond to a threat to their religious identity as their motive for joining. Almost three-quarters said they “hated” other faiths.

The ISS is not alone in thinking that the government is inflaming the situation. A Human Rights Watch report found strong evidence that the anti-terrorism unit is responsible for extrajudicial killings and disappearances .

More killings recorded

In research conducted in Kenya between November 2013 and June this year, the human rights watchdog documented at least 10 killings, 10 enforced disappearances and 11 cases of mistreatment or harassment of suspects where there was strong evidence of the counter terrorism unit’s involvement, mainly in Nairobi.

Amisom’s hope is that by the time of the 2016 elections Somalia’s federal government will have developed sufficient capacity to run its affairs independently and that any terrorist threat will be contained by the Somali National Army.

“We are focusing on 2016 – what happens after elections and the environment that will be prevailing at that time. An exit will much depend on the security situation,” Akiiki said.

“Assuming all is okay, Amisom forces will begin to size down as a UN peacekeeping force begins to take shape and takes over the mission.”

Akiiki said Amisom soldiers and police now numbered 22 126. The largest single commitment is from Uganda, which has sent more than 6?000 uniformed personnel, followed by Burundi, with more than 5 400, Ethiopia (nearly 4 400), Kenya (more than 3 600), Djibouti (1 000) and Sierra Leone (850).

Some success in fighting terrorism

Operation Indian Ocean has enjoyed some success: so far eight towns have been won back from al-Shabab, restricting its ability to raise funds through taxes and other financial exactions. Its predecessor, Operation Eagle, captured 10 towns.

Amisom and the Somalia National Army now controlled more than 90% of Somali territory, Akiiki said.

He added that, although no major centre was now under full al-Shabab control, the movement remained active in some villages.

But al-Shabab’s knowledge of the terrain, its ability to melt into the civilian population, and flexible, shape-shifting guerrilla tactics work against Amisom’s goal of neutralising it completely.

A leaked UN report this month warned that the movement remains as deadly as ever, helped by a corrupt Somali government.

The report claimed that weapons sent to the Somali National Army had been seen openly on sale in at least one market where al-Shabab agents bought arms.

The UN Security Council last year allowed a partial lifting of an arms embargo against Somalia to allow the national army to rearm.

The report added that air and drone strikes were doing little damage to al-Shabab in the long term and that it was still capable of mounting successful attacks.

Bomb attacks on the increase

In Kenya itself, its bomb attacks have increased, and it has introduced more sophisticated weapons, including magnetic vehicle bombs commonly used in Afghanistan and Iraq. In this way it has benefited from a transfer of battlefield knowledge among jihadist militants.

Akiiki would not comment on the cost of the operation but figures in the public domain show that Kenya spent more than 26-billion Kenyan shillings (R3-billion) in the first year of the war alone, a figure that could be higher if the cost of combat equipment is factored in.

The biggest cost is now being shouldered by Amisom, which pays KSh88 480 a month to each of its soldiers in Somalia and a once-off KSh4.3-million to dependants of each Kenyan soldier killed there.

The European Union pays troop allowances and “other related expenses” and the UN compensates Kenya for salaries paid to soldiers to the tune of about Ksh5-billion a year.

The EU support to Amisom is funded under the African Peace Facility. More than R14-billion was budgeted for between 2004 and 2013.

The Kenyan treasury has complained about the slow pace of refunds, which has put it under budgetary pressure. Government expenditure on security rose by more than 10% this year to about R22-billion.

Commitment to fight terrorism

In August this year, United States President Barack Obama announced a joint Security Governance Initiative at the African leaders’ summit, enabling six countries – Kenya, Ghana, Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Tunisia – to draw down funds to fight terrorism. It committed $65-million for the first year of the initiative.

Nevertheless, underfunding, and the consequent shortage of equipment vital to countering irregular forces, are clearly hampering the Amisom campaign.

“The key challenges have been lack of force enablers, such as fighting helicopters and utility helicopters, the poor road network, clan conflicts and limited troop levels until last year when Ethiopia joined,” Akiiki said.

He said Amisom was conducting joint operations with the Somali National Army. When a town was captured, they would defend it together, allowing the national force to take a lead “as we mentor them to develop their own capacity to take care of their own security”.

But despite Akiiki’s fairly upbeat assessment, it will not be easy for Kenya to extract itself from the Somalian quagmire, certainly not before Somalia’s election in 2016.

The Kenyan government justifies the country’s engagement by saying it had no choice. Its former minister of internal security, the late George Saitoti, said the decision to invade Somalia was in response to an al-Shabab recruitment campaign among “our unemployed youth [turning] them into terrorists”.

But many now argue that Kenya does have the option of pulling back troops to the border and creating a buffer zone.

Increasingly, the country is confronted by an unpalatable dilemma: to continue a costly and increasingly unpopular war or – like the US in Iraq – to exit unilaterally, with egg on its face.

Wounded, the organisation remains dangerous

It is split and limping, but the al-Shabab jihadist group terrorising East Africa is still a deadly force.

Like Boko Haram in Nigeria and Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, the movement – which means youth in Arabic – is merciless, killing even pregnant women and children.

Philosophically, it is an offshoot of the ultraconservative, puritanical Wahhabist strain of Islam.

It opposes modern forms of entertainment, including watching sport, and stricter members prohibit their women from wearing bras on the grounds that they highlight their breasts.

Formed in 2004 as the militant wing of the Islamic Courts Union, it has caused untold suffering in the Horn of Africa for almost a decade.

Its leader, Ahmed Abdi Godane, was killed by United States drones in an air strike on September 1 this year. Now without a substantial head, al-Shabab’s command structure is unknown and the organisation seems at its most vulnerable.

The emergence of a new leadership has been slowed by an internal power struggle that reportedly saw the elimination of potential successors.

After taking over in 2008, Godane allegedly put the group back on the map after re-engineering it as an al-Qaeda network.

The result was a series of deadly attacks culminating in the Westgate shopping mall siege in Nairobi five years later. He also recruited a host of new fighters from abroad, using the new network.

Al-Shabab has kept Mogadishu on its toes with incessant attacks, after losing it to a Western-backed government in 2011.

It controlled the capital and southern Somalia from 2006 to 2011 before being forced out of the city by African Union peacekeeping forces.

It has also been weakened in the south, losing control of major ports to the AU Mission in Somalia, disrupting its ability to rearm and resupply.

Its revenues, largely based on charcoal exports, have also been disrupted. A recent Interpol report says that the charcoal traffic and taxation of the ports brought it up to $56-million a year.

Other funding comes from informal taxation at roadblocks, ports, businesses and farms – and ransom from the kidnapping of tourists and seizing of ships in the Indian Ocean.

Conservationists claim that the gang is also funding its campaigns by large-scale elephant poaching in Kenya and elsewhere. The group is said to receive financial aid from individuals and Middle Eastern countries, particularly Qatar, that support its ideology. – Paul Wafula

* Got a tip-off for us about this story? Click here.

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism (amaBhungane) produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for our stories, activities and funding sources.

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism (amaBhungane) produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for our stories, activities and funding sources.