“The role of the artist has always been to provoke debate and to raise issues for discussion — even contentious ones,” says Peter Rorvik, the secretary general of the creative civil society organisation Arterial Network. “[And] the function of the artist has been to precipitate change.”

In South Africa, where cultural resistance towards apartheid was a powerful tool in shaking up the old guard, the artist as a catalyst for change has deep roots. But more recently, artists’ works have sparked riots and spurred debate from South Africa to the United Kingdom.

Controversy has swamped South African artists such as Brett Bailey, whose Exhibit B show was shut down in London in September after vigorous protests, and Cape Town-based collective Dookoom, whose music video for their song, Larney, Jou Poes, resulted in the group being threatened with legal action by civil rights group Afriforum.

Rorvik criticises both cases, particularly the shutting down of Bailey’s Exhibit B, which the Barbican Centre cancelled following protests by anti-racism campaigners. “Exhibit B certainly touched a nerve and highlighted the need for ongoing debate on racism and history,” he says. “But while dissenting voices have a right not to see the work, they do not have the right to force a closure.”

Rorvik, the former director of the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s Centre for Creative Arts, spoke to the Mail & Guardian ahead of the annual African Creative Economy Conference in Rabat, Morocco, co-hosted by the Association Racines/Arterial Network Morocco. The conference is expected to draw hundreds of artists, activists, representatives of civil society and African governments, who will address issues faced by the continent’s cultural and creative industries.

Peter Rorvik of Arterial Network. (Supplied)

Rorvik, who will be giving a talk at the event on “culture, artists’ rights and democracy in Africa”, says: “The artist has the right to create art, audiences have a right to see it; these are basic rights enshrined in most country’s Constitutions around the world. It is a fundamental role of the artist to make us think.”

‘Disgraceful example of intolerance’

Discussing other instances in contemporary South Africa where the freedom of expression of artists has been challenged — such as the protests and uproar in 2012 around Brett Murray’s The Spear, a painting of President Jacob Zuma with his genitals exposed that was defaced by two attackers, Rorvik asserts that “the role of artists as agents of change should be celebrated, not prosecuted”.

But in a nation where song, visual art and theatre productions were some of the cultural devices used to disseminate news of a country suffering under apartheid, the power of art is not overlooked. However, the reactions to controversial artwork by both the apartheid and post-apartheid governments have at times been unfortunately similar.

And despite it being two decades into South Africa’s liberation, events such as the Murray and Dookoom drama have highlighted just how little progress the country has made since the National Party government imposed laws such as the 1963 Publications and Entertainments Act, which stifled freedom of expression.

The Act created a central body, the Publications Control Board, to decide whether publications (excluding newspapers), objects, films and public entertainment complied with the Act’s strict moral and political codes or were indecent or obscene or politically unacceptable.

“I would love to say that South Africa is making progress, but regrettably I think the opposite,” says artist and writer Sue Williamson, who spoke to the M&G in mid-October from London, where her work was on show at the Goodman Gallery’s stand at Frieze Masters — part of the city’s Frieze Art Fair. Williamson says that “if art is provocative, it should be considered, discussed, analysed, criticised or celebrated, but never avoided”.

Artist Sue Williamson. (Mikhael Subotzky)

Williamson, the author of Resistance Art in South Africa, which documents art movements against apartheid, spoke of an incident in 2009, when the arts and culture minister at the time, Lulu Xingwana, reportedly stormed out of an exhibition of Zanele Muholi’s because she considered the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual and intersex activist and photographer’s images of black lesbians “pornographic”.

“This was a disgraceful example of intolerance from a minister, whom one would have supposed was familiar with the terms of the Constitution, and was in support of cultural freedom of expression.”

Bill of Rights

Section 16 of the Constitution’s Bill of Rights states that citizens’ “right to freedom of expression … includes freedom of the press and other media; freedom to receive or impart information or ideas; freedom of artistic creativity; and academic freedom and freedom of scientific research”.

Despite these guarantees, scenes such as the Xingwana-Muholi saga recall the heavy-handed manner in which art that questioned the status quo was dealt with when restrictive apartheid laws and bodies governed cultural output.

In 2012, the ruling party’s call for Murray’s “distasteful” painting of Zuma to be removed “from display” as well as from the City Press website and for all “printed promotional material” relating to the artwork to be destroyed, harks back to an incident involving the late Ronald Harrison 50 years earlier.

Harrison was arrested and interrogated by the apartheid government in 1962 for his depiction of former ANC president Chief Albert Luthuli as a crucified Jesus in the painting Black Christ. The artwork, unlike Murray’s, was not defaced — it was smuggled out of the country and returned in the late 1990s. It now hangs in the South African National Gallery in Cape Town.

Doing away with restrictive laws

In an interview with the New York Times in 1997, Harrison recalled how the apartheid government intimidated him. “They’d come in with smug looks — oh, they were subtle. They wanted to know the names of the people who’d smuggled it out. Then, when they were finished with you, they’d drop you off in the middle of nowhere.”

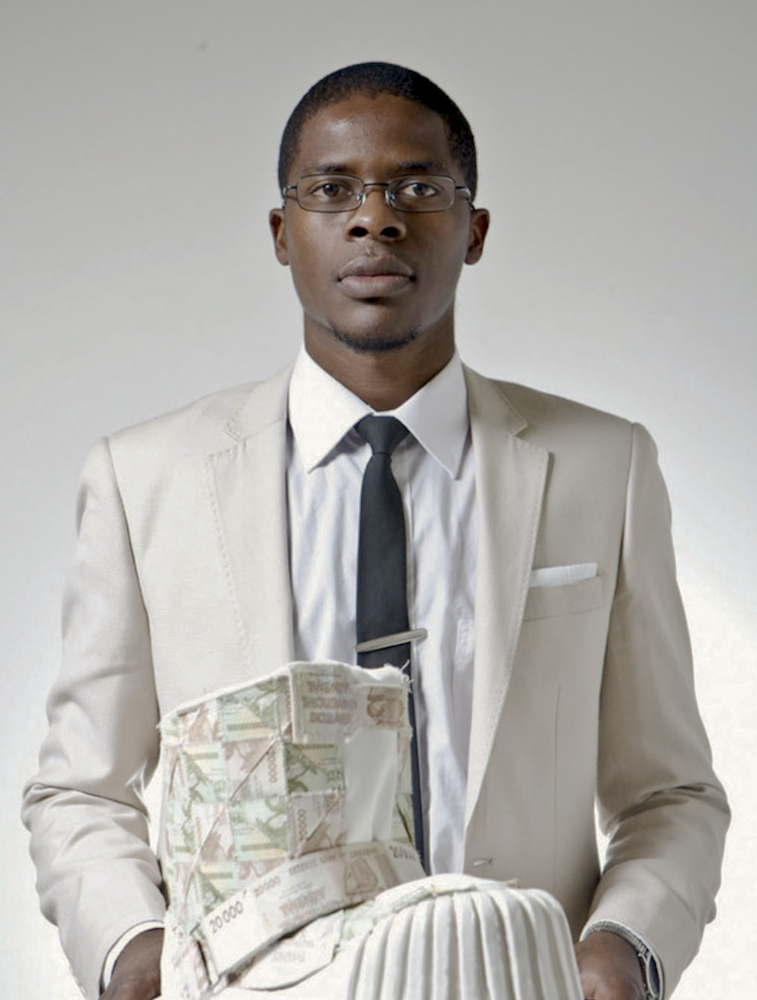

Artist Gerald Machona. (Supplied)

Decades later, the country’s 1996 Constitution ushered in a new era of freedom for the arts. The Film and Publications Act of 1996 repealed draconian apartheid laws that governed the work of artists, writers and filmmakers. The passing of the Act also resulted in the establishment of the Film and Publications Board and Review Board.

Writing for FairObserver.com in July, journalist Peter McDonald drew comparisons between laws that governed literature during the National Party’s rule and contemporary South Africa.

“In legal terms, then, the new Act represents an emphatic break with the past,” he wrote. “Reflecting internationally agreed norms, and the guarantees enshrined in the Bill of Rights, it rejects censorship in favour of classification, focuses on relatively measurable questions of harm, avoiding any reference to value-laden ideas of blasphemy or moral repugnance (obscenity, in other words).”

Self-censorship

Last year, Jahmil XT Qubeka’s movie Of Good Report was banned by the Film and Publications Board, which said it contained child pornography, despite the character in question being older than 20. The ban was lifted shortly afterwards, but not before it had generated heated debate that questioned the board’s classification role.

Zachary Levenson, writing on the blog Africasacountry.com, said the banning of the film “would be like banning episodes of Beverly Hills 90210 for suggesting sex between minors, even though Luke Perry was in his 30s for much of the filming”.

Rorvik says that this type of reaction to art tends to lead to artists censoring themselves. “Self-censorship [results from] repression and intimidation. So many people in Africa feel threatened [but] rarely speak out about censorship and the abuse they suffer.”

Rorvik says “censorship in other countries in Africa is far more restrictive than in South Africa” and cites “the recent censoring of the films Difret in Ethiopia and The Stories of our Lives in Kenya, imprisonment of rappers in Morocco and Tunisia, vandalising of an art gallery in Senegal, assault of a filmmaker in Cameroon et cetera”.

Gerald Machona, a Zimbabwean-born, Cape Town-based performance artist and sculptor, says: “South Africa has one of the most liberal Constitutions in Africa and comes a long way from the apartheid ideology.” But the artist, whose work centres on identity politics and the politics of representation, questions how free freedom of expression really is in South Africa.

“You should ask yourself, who is given the freedom to express? There are certain spaces within the spheres of our society where people are not given that freedom.”