Flash 29: Alcoholism

Locals say that Rawsonville appears in the Guinness Book of World Records as having the highest rate of alcoholism in the world, but I am inclined to believe, after fruitless attempts to confirm the rumour, that this might be an urban legend. But even if the claim is false, the reality of alcohol addiction in the Western Cape constitutes a national health disaster.

Not only does alcohol dependency among farmworkers lead to liver disease, emotional disturbance, aggression and forms of chronic domestic violence, but children also suffer from the highest rates of fetal alcohol syndrome in the world and hunger associated with the purchase of liquor rather than food in household economies. Children with fetal alcohol syndrome experience stunted physical growth, slower intellectual development and a greater vulnerability to infectious illness. Children also suffer extreme forms of physical and verbal assault by adults under the influence of alcohol.

Riaan performed the following song during one of our radio workshops:

Oom Muis se boortjie/ Hy kry ’n skoortjie/ Want hy kom/ Want daar was ’n fight op onse blok/ Die stry het gekom oor ’n bottel en ’n dop/ Die bottel het gebreek/ Iemand word gesteek/Sommer deur die gevreet/ En deur die skouer/ ’n Mens sien net houe/ punt nommer drie/ Dis twee gevreet/ en kwaai/ dis violence/ Hy gee vir smokkel hy het geen licence/ Van ’n bietjie wyn/ Dit pop jou brein.

Uncle Mouse’s collar/ He gets into an argument/ Because he comes/ Because there was a fight on our block/ The fight was because of a bottle and a drink/ The bottle broke/ Somebody was stabbed/ Right in the face/ And in the shoulder/ A person just sees punches/ Point number three/ He is two-faced/ and angry/ It’s violence/ He smuggles without a licence/ Because of a little wine/ This pops your brain.

Monica Wilson, a South African anthropologist who trained a generation of skilled ethnographers, conducted research on the nature of alcoholism and labour extraction from “villages” in the Western Cape. She compared her findings with evidence from England that alcoholism among farmworkers decreased with improved housing.

She wrote: “It is conspicuous that alcoholism among farmworkers decreased markedly in England with improved houses, which meant that a man, at the end of the day, had somewhere comfortable to sit other than the pub, and with the development of alternative recreation, first cinemas and motorbikes, then radio and television. Young men began to take their girlfriends to the cinema, rather than drinking in the pub, then married couples listened to the radio and watched television.”

Wilson’s observation echoes the contemporary lament of youths in urban townships and on farms where there are few recreational or entertainment options other than self-created modes of activity.

Flash 37: Riaan

Riaan was 12 years old when we met in 1997. He lived with his father, Johan, in the house of his birth, and although he had two older sisters and three older brothers, none of them lived at home. Riaan’s mother, had died of tuberculosis in 1996, after which his domestic responsibilities increased dramatically and plunged him into a repertoire of chores that were usually allocated to girls and women.

By the age of nine, Riaan worked in the vineyards pruning, planting, digging new trenches, removing rocks from the soil, weeding, spraying pesticides and harvesting. He helped his father, who worked from 7am to 6pm, for which he earned a little pocket money for sweets. Riaan said: “I get almost nothing, just R5 a week for helping in the vineyard six full days a week. I can buy nothing, only sweets, chips and chocolates.”

In one conversation Riaan told me: “I enjoy the pruning season. To cut the grapes, throw them in the basket and carry them out”, and in another, “I don’t like working with the spade and shovelling, picking up stones, it makes your back sore. At night when you have to stop working, then you are tired, then you still have to work at home, and you still get scolded for not working properly.”

Riaan’s legs caused him considerable distress. He said: “It gets very ugly in the winter from working in the poisonous dust.” He rubbed Vaseline on his legs to stop them from itching, but found that the Vaseline was not effective. He felt unable to ask his abusive father for help, and suffered alone. “Drinking is killing my father,” he said. Even though the dop system was illegal, the farmer continued to “reward” Johan with a bottle of wine each day, and when that was finished Johan brewed his own beer.

Pammie, sister to Riaan’s mother, said: “This stuff, this drunken stuff. Let’s just say this King Kong. Have you seen the packet in the store, this boetie or sisi with the barrel on the head, now they call that King Kong. Riaan’s father makes this. I’ll show you a packet of the yeast one day.” By 2006, Riaan had continued to maintain his sobriety and had started a business selling cheap liquor to farmworkers in the wake of stronger anti-dop enforcement.

Flash 32: School as sanctuary

In 1998 and 1999 I visited farm schools that catered specifically for children who lived on farms. Some of them lacked basic amenities such as electricity, running water or toilets, while others were better equipped. None of the schools had anything approximating a library or shelves with stimulating games or outdoor interactive play areas. It was human energy rather than material wealth that made it possible for some of these farm schools to flourish, and at one school a principal named Mr Petersen dedicated himself to raising enough funds to operate an excellent kitchen and feeding programme.

Leafing through the children’s health records at schools, I found that chronic hunger, malnutrition, fetal alcohol syndrome, tooth decay, head lice, stunted growth, skin infections from pesticide contact, poor hygiene, tuberculosis and upper respiratory tract infections were the main causes of local childhood suffering.

But sickness was not the only reason that children missed school. Absenteeism was also owed to their work responsibilities at home, and when they did attend school during intense periods of extracurricular work, Petersen commented on their inability to concentrate.

Flash 45: Sobriety

Hendrik was one of the young men on the farm who “chose” a life of sobriety. Like his younger sister Sanna, he claimed to have been greatly influenced by his primary and high school teachers who instilled considerable fear about alcohol in their pupils. Sobriety emerged as the antidote to the reproduction of servitude. For Sanna, Hendrik and Riaan, sobriety was the key to liberation from the particular genealogy of their inheritance. Sanna framed her intended sobriety as a way out of her social inheritance.

She said: “My father hurt me when he was drunk, a hiding for nothing. My mother just scolds me. I ask them to stop drinking but they ignore me. The farmers give them wine, one bottle every night. My ma and pa share one bottle. The teachers told us it was a bad thing. When I grow up I won’t drink.”

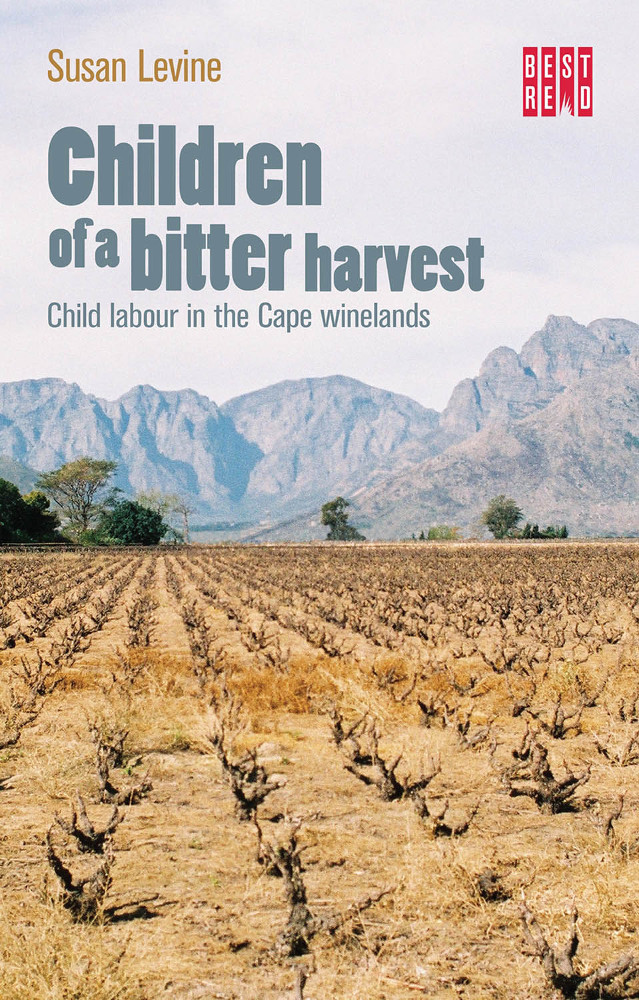

Children of a Bitter Harvest is published by BestRed, an imprint of HSRC Press