It is said that the bones of the dead become restless when buried in unknown lands. But the repatriation of the remains of anti-apartheid journalist Nat Nakasa, who lay buried in the United States for years, did not bring peace with them. It resuscitated the scars and disorganisation created by apartheid.

Kemang wa Lehulere’s solo show, To Whom It May Concern, pays homage to Nakasa’s ghost.

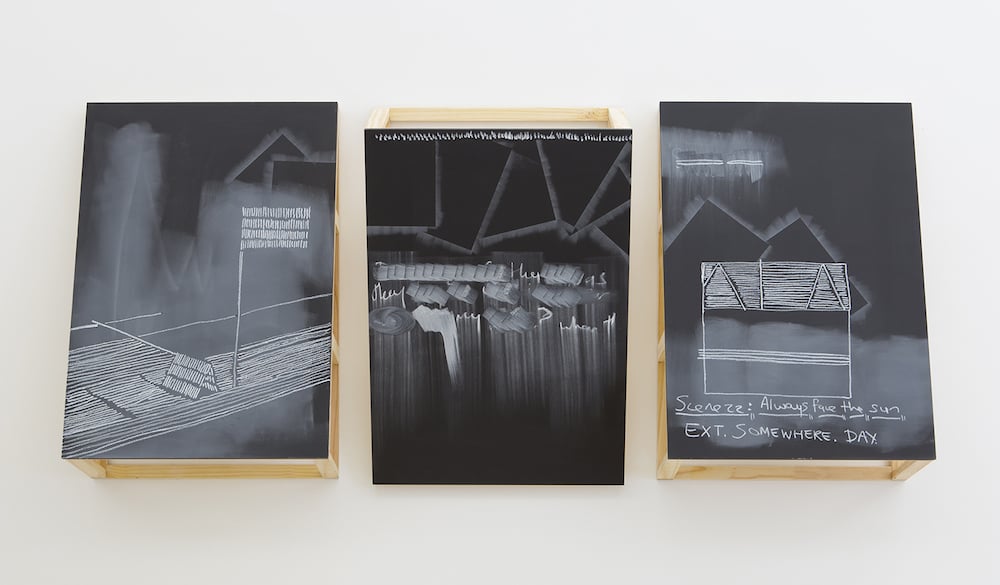

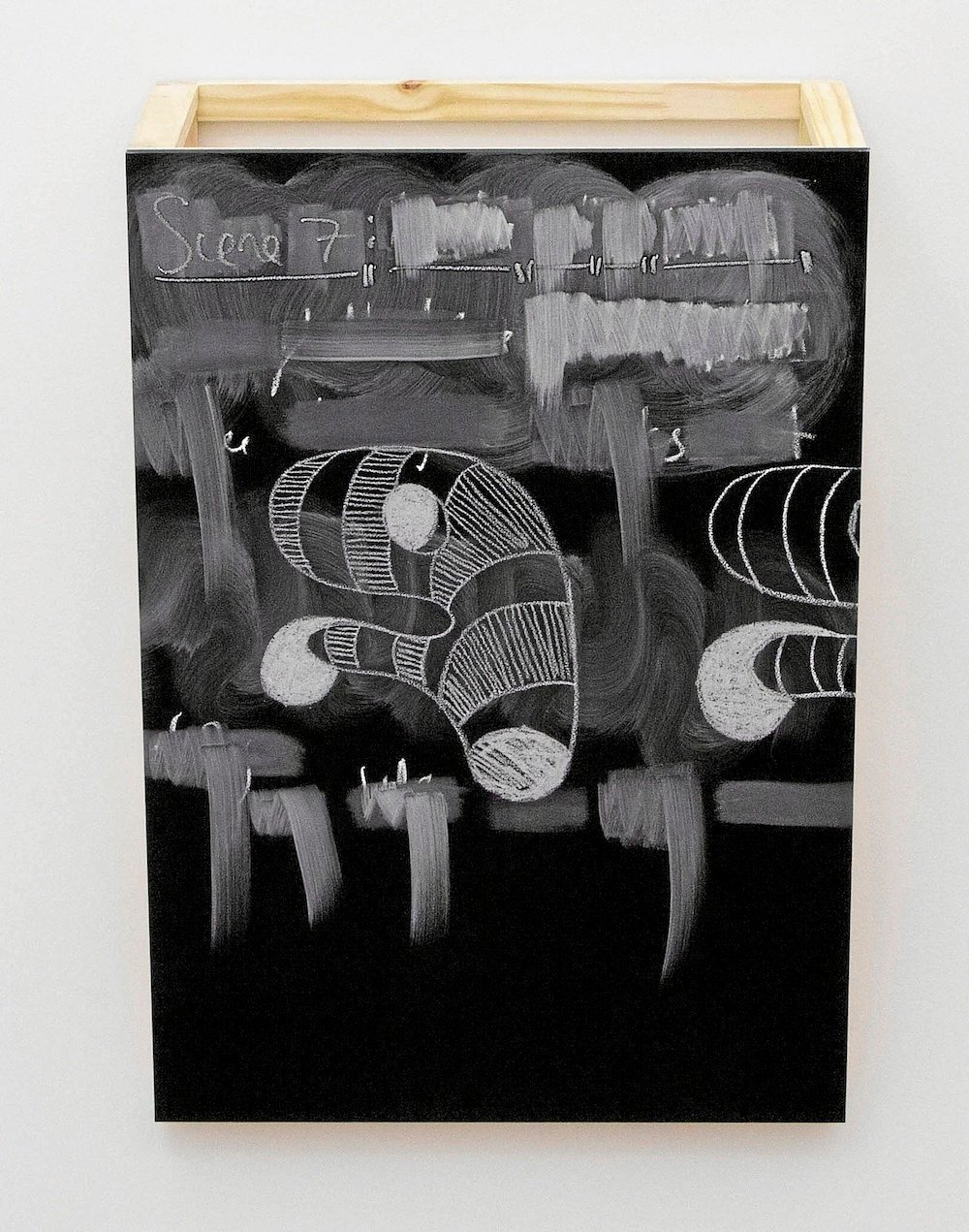

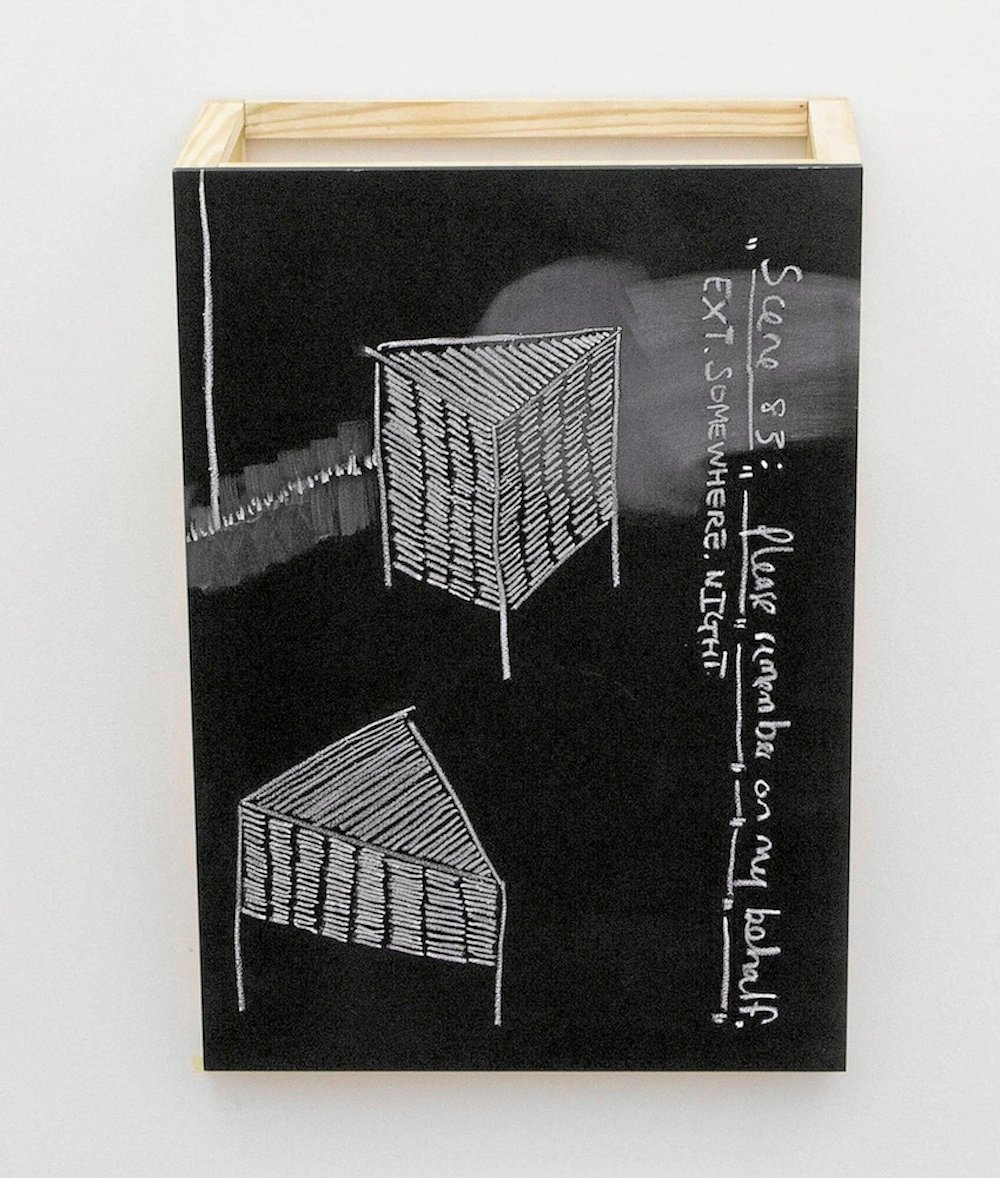

As if speaking to the unknown, Lehulere’s show is a visual letter, comprising video, sculpture-cum-installations, ink drawings and chalk murals. It is a volatile minefield of familiar things, impressions and characters that have become almost autographic signs of the oeuvre of the multi-award-winning artist.

I’m referring to the bones, the sharpener, the digger, music stands and faceless characters. Their reappearance survive the sterility that often comes with repetition. The resurfacing of relics gives a sense of something ongoing, transmuting and pliable, especially in his sculptural works.

This method gives an impression of inquisitiveness, a sense of a pupil’s journey, filled with errors, erasures, digging and blackboards. Wasn’t the idea of the “forensic investigator” central to Lehulere’s previous works?

It is no surprise that To Whom is inspired by Japanese composer and artist Mieko Shiomi’s Spatial Poems. Similar to the Fluxus movement, which worked in a “transcategorial” way and of which Shiomi was part, Lehulere juggles a compendium of media, ideas and issues, as though they are all related to a single narrative form. There is a sense of being unresolved, if not defiance of completeness – an “indeterminable avalanche of categories”, as artist Robert Smithson said.

Such discontinuity, mutability, disorientation, confusion and shift were key to groups such as Fluxus and to art more generally, as Fluxus associate Robert Morris suggested.

This isn’t shown just in Lehulere’s relative disconnection. Conceptually, it extends to his sculptural-cum-installation work and ink drawings, which are suggestive of abstraction. More typically, the work barely escapes the threatening trace of abstraction operating from a distance in most contemporary art practices.

Gesture of repatriating Nakasa

For the viewer unacquainted with the potential permanence of some constitutive features, there is a danger of reading the art at surface level – or, more spuriously, labouring on reading the present works as isolatable objects with individual titles, as opposed to a large instalment. The cataloguing of works such as mass-produced porcelain dogs with pointed ears, oddly positioned next to disassembled school desks, gaping suitcases and chalk inscriptions on blackboards, makes it seem rather prolix.

In the first room where homage to Nakasa is more obvious, we see gaping suitcases filled with soil and blades of grass. It is said that the artist visited Nakasa’s grave in New York and did a little jig. There is a curious political-theological hint at play here, which is both the symbolic gesture of repatriating Nakasa and the metaphorical return of humanity to earth.

Central to colonial Christian legacy wasn’t just the denial of the oppressed humanity but also land dispossession. How then do we think of home without simultaneously pairing it with landlessness? Under such conditions, blacks aren’t just nonhuman, they are also landless, dead or alive.

Perhaps, like muted dogs staggering in the contradiction of existential despair, easily portable whether dead or alive, black lives are inconsequential.

Recently the black world screamed into a void #blacklivesmatter. Black blood drenched the streets of the US and the world refused to inscribe on its bosom #jesuisTrayvonMartin. In his reflection on Home and Exile, Lewis Nkosi recounts that the blacks of New York weren’t any less ridden with pain than his counterparts in his flattened Sophiatown.

In To Whom It May Concern, with the props littering the floors, the journey of the wanderer not only seems to have abruptly ended but also the silence of the forlorn ceramic dogs dispirits the space with a beguiling melancholy. The ubiquity of abstract inscriptions, erased narratives and deconstructed objects shows Lehulere grappling with both the malleability of matter and the irreparability of some things. As Lehulere said: “It is a gentle form of resistance.”

To Whom It May Concern remains an interesting show, which at times can be challenging and confusing. But, as Morris argues, “art is an activity of change, of disorientation and shift … of the willingness for confusion … in service of discovering new perceptual modes”.

In this sense, the constant disjunctive overlapping and tip-toeing across plains is itself part of the work. Though the letter has arrived, there is neither the receiver nor the world to decipher its black grief.

To Whom It May Concern runs from January 22 to February 28 at the Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town