More than 2.5-million Syrians had fled across the country’s borders and 6.5-million were internally displaced at the end of last year

The Buena Vista Social Club are one of a handful of “exotic other” bands who are genuinely recognised and appreciated for their individual personalities; Ibrahim Ferrer, the lead vocalist in a flat cap with a cigarette on his lower lip; Omara Portuondo, the 84-year-old dancer-singer who elevates Buena Vista’s glamour to an untouchable status; the silver-haired, slickly dressed pianist Rubén González; and Eliades Ochoa, the tres and cuatro guitarist who must surely have been born wearing his trademark cowboy hat and boots.

A dozen others have come and gone as the band have toured off the back of their 1997 eponymous debut, an album largely consisting of recordings celebrating the golden age of Cuban music.

I arrive at Buena Vista’s London hotel room as Portuondo and Ochoa are pouring over the booklet of their new release, Lost and Found. The tour manager sits legs outstretched on the floor and lets out a horrible cough every few minutes – “he’s not a heavy smoker, just nursing a bad cold”– with his arm around a boxful of albums.

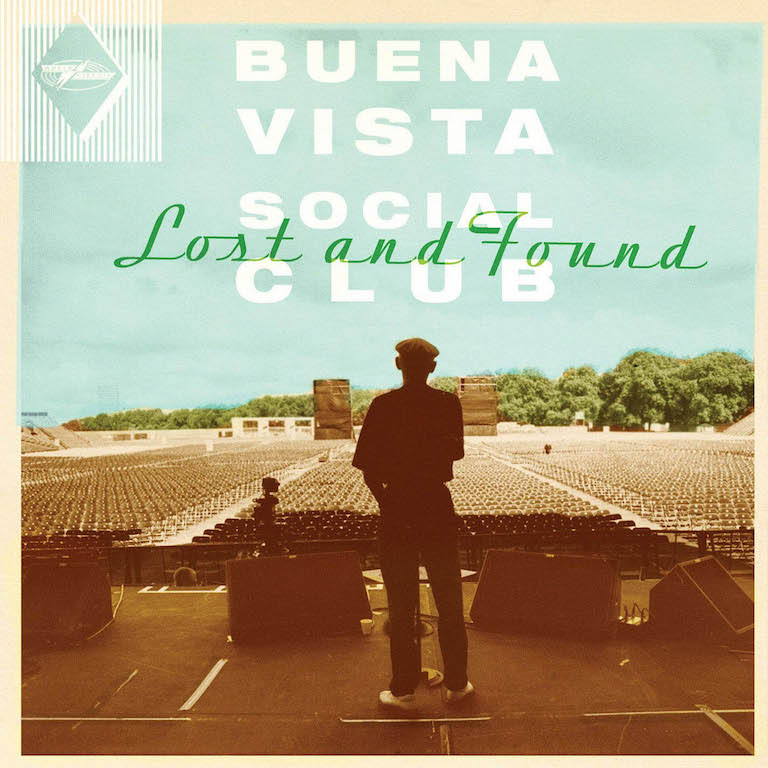

This is their first release in nearly two decades, and features a selection of live and previously unreleased tracks. Ferrer again features as the solitary cover figure. Where before he was captured walking (or dancing?) down a Havana backstreet, here he contemplates the empty seats of a vast stadium in what looks like a pre-gig ritual.

The opening track, Bruca Manigua, is a joyous live performance to a sell-out crowd at Paris’s Zenith arena. The crowd whoop and clap, and Ferrer responds to the enthusiasm by drawing out his “si rrrrrrrrrramento” for all its worth.

Omara Portuondo and Eliades Ochoa

I ask them if they are surprised by Buena Vista’s huge success. But Portuondo and Ochoa are engrossed in the booklet, and are more concerned about trying to remember the name of “some fat guy” – “el gordo” – who is seen playing a trumpet on the final page. After much giggling, Portundo responds.

“We’ve achieved something that has long survived in our culture, so, no, I’m not surprised. I’m more proud and fulfilled. I have listened to this music since I was a child because it represents Cuba. We wanted our traditional music to live on and to enchant the world, and this is what our tours achieved. It has been an incredible part of my career and life.”

Then, of course, there’s the fact that the world enjoyed Cuban music long before Buena Vista, thanks often to the previous careers of many of its members.

“The first really popular song from Cuba was called El Manisero [The Peanut Vendor]. Loads of artists have covered it and it’s still huge. This [gestures to the booklet] success came afterwards. In the Fifties, Compay Segundo [composer of Buena Vista’s hit track Chan Chan] travelled a lot,” Portuondo says.

“Segundo was in a fantastic duo called Los Compadres,” Ochoa adds. “They went to the Dominican Republic and Mexico, which helped make Cuba a major force in Latin music.”

Of their own solo careers, Ochoa was a big draw card for the record label World Circuit in connecting its two countries of focus: Cuba and Mali. The original Buena Vista concept was to record using musicians from both countries, but this was abandoned because of visa complications. The idea did materialise with 2010’s Afrocubism, a collaborative album featuring Ochoa, several other Buena Vista members and Malians Toumani Diabaté and Bassekou Kouyate.

Several band members have come and gone but Compay Segundo (below left), who died in 2003, was one of the main musical inspirations.

Ochoa says: “I played with them, and they played with me. It was a beautiful thing working with African musicians, but the important thing I want to stress is that it was a school for them and it was a school for us.

“I also worked with Manu Dibango in a similar way. The African roots are big in our own music because we have African blood.”

Portuondo says: “My father was an Afro-Cuban baseball player, so for him in particular the Africa connection was very real. My mother was a woman with a strong heart.”

Portuondo makes a heart hand gesture, her blood-red nail varnish adding extra imagery. “In my house everybody was singing, just like in every family.” If I’m honest, my family aren’t singers.

“Doesn’t everybody’s mother sing?” Portuondo asks. “When I was rocked as a baby, my mother always sung to me. When I grew older, my parents introduced me to a composer called María Teresa Vera, who was a massive influence. I learned about her music, and in particular the song Veinte Años. We covered this on Buena Vista Social Club.”

“Bolero, guaracha, cha-cha-cha, son, changüí, rumba, mambo, campesina … we have an inexhaustible source of all these kinds of music,” Ochoa says. “When you say son cubano everyone in the world knows what you are talking about, but our music goes beyond that.”

Portuondo and Ochoa break into a rendition, hands clapping, of Guantanamera, a universal Cuban folk song often misheard in the English-speaking world as “One Tanamera”.

From here the possibilities are endless: “One Frankie Lampard, there’s only one Frankie Lampard …” It seems rude not to join in the singing, and I do so much to Ochoa’s amusement.

“Exactly! That’s a guajira song – country music. I’m from the country, hence the hat. In my artistic life, the most important thing is to be in my element and it’s still not over yet.”

Why are they releasing Lost and Found now after all this time?

Ochoa replies: “This is our goodbye tour, so it seems fitting. The songs haven’t been released yet because Buena Vista Social Club still has so much attention. Cachaíto [Orlando López, double bass] had his own record, as did Aguaje [Jesús Ramos, trombone]; there have been many offshoots. When we listen to Lost and Found now, the success of Buena Vista means we don’t remember the individual concerts.”

The 13 tracks of Lost and Found range from the uplifting, tourist-friendly kind to the untamed sounds of indigenous Cuba. The latter style is perfected on Black Chicken 37, a wild instrumental that thumps its rhythm out in a drum ’n bass call-and-response exchange.

Ochoa says: “That’s the one in two meter, no? The rhythm is wonderful. Orlando ‘Cachaíto’ López was on double bass, but he could play everything. He had a big role in all the Cuban carnivals, and I used to sing and dance rumba with him before Buena Vista.

“Miguel Angá Díaz is on percussion; the rhythm is very African here. He was an amazing musician who died suddenly aged 45. This is Angá …”

Portuondo finds a picture of Angá, bare-armed and muscular, surrounded by hand drums in a recording session. Angá’s twin daughters went on to form Ibeyi, who are carving out a niche for themselves by fusing French, Cuban and Yoruba influences. “Angá was magnificent,” Ochoa says.

“Here’s Ibrahim and Cachau, the trombone player. He was the director of the orchestra, before the days of Ibrahim. All the time he was smiling,” Portuondo adds.

She turns a few pages. “This is my home, on the 12th floor.” The picture shows a silhouette of Portuondo – high cheek-boned, smile, eyelashes – looking out over Havana. Washed clothes hang above the windows.

How do they stay so fit and healthy? Portuondo laughs. “We were born in Cuba. We have sunshine all the time. Cuban coffee … Cuban rum … Cuban women [more laughter] … and, of course, we have the music.”

Lost and Found is released by World Circuit