Yellow dreams of finding 'pigeon egg' size diamonds to buy a farm for his family

Yellow built his house by selling ganja. It has a carport, tiled floors and satellite television, all paid for in cash. The neighbouring homes, which are packed tightly on a side road in Retreat, Cape Town, have rusting roofs and bare concrete walls.

When I visited one evening last December, his wife was preparing dinner – strictly vegetarian, befitting Yellow’s Rastafarian beliefs. We sat on matching sofas in the living room.

“I want diamonds so I can settle my family and retire,” he told me.

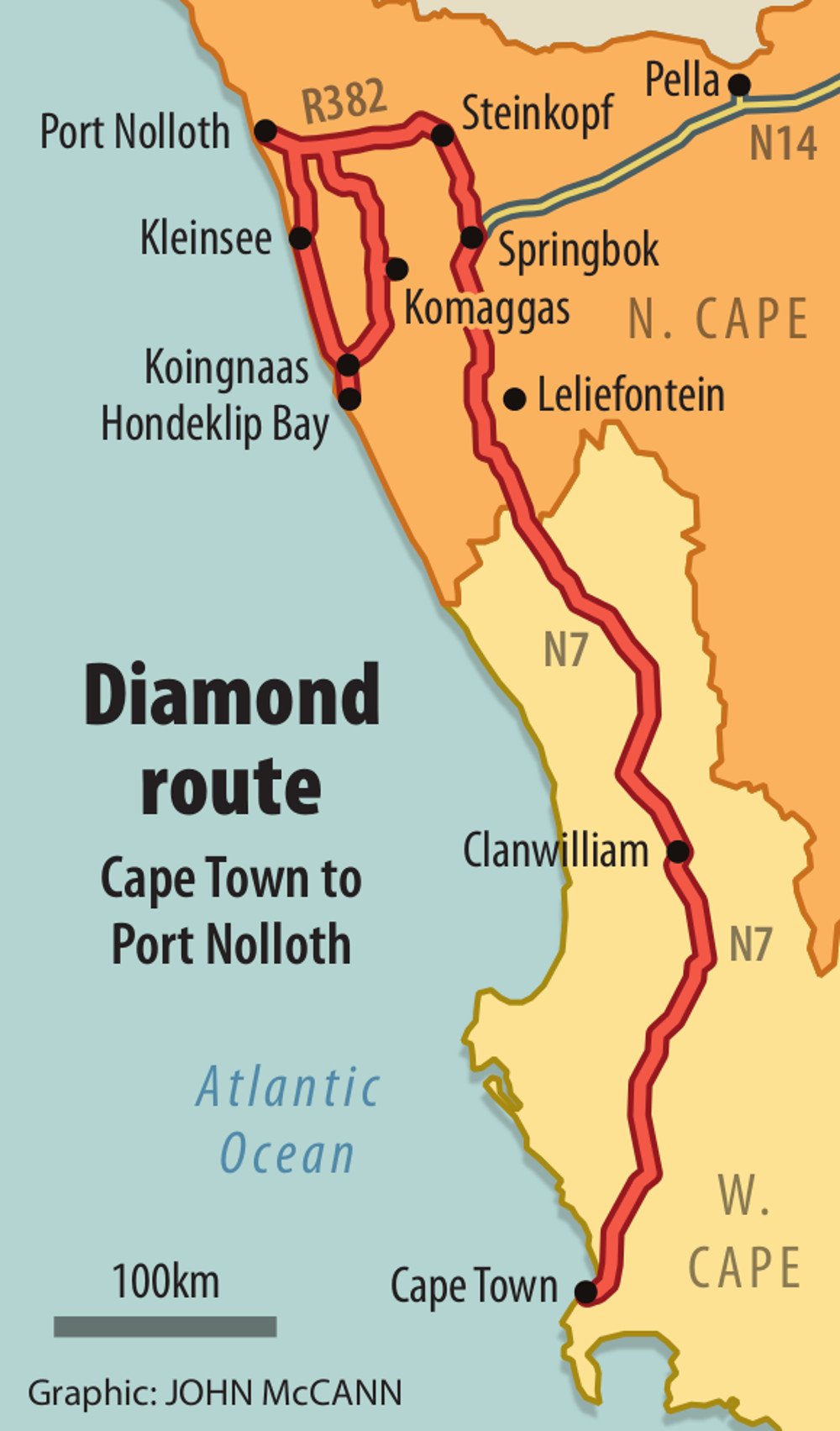

But to do this he needed to return to Namaqualand in the Northern Cape, where teams of illegal diggers sell uncut stones on the black market.

I wanted to find out more about the trade, which supports hundreds of families in an area beset by chronic unemployment, and offered him a lift in a borrowed Land Cruiser.

Four days later, at dawn on a Saturday, we left.

Supplies

Yellow was wearing a fuzzy red beret over his dreadlocks when I collected him. He kissed his wife goodbye and packed medicinal herbs, a spade, steel pegs and a jackhammer into the boot.

The roads were empty; we were soon at the edge of the city, travelling through fields of wheat.

“Selling ganja became too risky,” he explained. “I quit as soon as my house was finished.” A Cape Flats bush doctor, Yellow still earned a modest income trading indigenous herbs such as buchu and wild garlic. He needed more money to secure his family’s future. His four sons, aged between 22 and 34, were living at home; none had stable jobs. His nine-year-old daughter had just finished third grade.

“I want to buy a farm and set them up,” he said as we drove. “My boys didn’t get the opportunity to go to college. They won’t find work easily. I’m going to give them a head start.”

The farm would be in Hermanus. It would produce herbs, essential oils and vegetables, have separate houses for each of his children and, in front of the main building, a stoep with a rocking chair where he could sit and smoke ganja, admiring the view.

‘Pigeon eggs’

His mission was to find a few “pigeon eggs”, or diamonds larger than five carats, to pay for the land. On the legal market, diamonds that size fetch wholesale prices of between R500 000 and R7.5-million. Selling to illicit buyers in Cape Town, Yellow hoped to make at least R100 000 a stone.

“I’m going to get me a nice packet,” he said, twisting his beard around a calloused thumb. “Enough to earn a few hundred thousand rand, perhaps a couple million.”

He folded his hands in his lap, leaned his head against the window of the cab, and fell asleep.

Uncut diamonds can fetch decent prices on the black market, but diggers face 10 years in jail if caught. (Photos: Alexander Joe, AFP)

Yellow was born in Retreat in 1960, six months before the suburb was declared a “coloured residential area” under the Group Areas Act. His mother ran a stall at the Adderley Street flower market. His father, a harbour worker, came from Mossel Bay. Yellow had 14 siblings and grew up in poverty. At the age of 17 he joined the navy but quit when he became a Rastafarian three years later, choosing to sell medicinal herbs instead.

Now in his 50s, Yellow is a short, robust man with a wide nose and unlined cheeks. When he unties his hair it falls below his waist. Nothing ruffles him. He speaks slowly and is prone to gazing into the distance and trailing off, particularly after smoking. He laughs easily and is comfortable around most people, although he says he prefers his own company. He proclaims himself a “professor of indigenous medicine” after more than 30 years in the trade.

Diamond discovery

Yellow first learned about diamonds in 2012, when he visited Namaqualand to sell herbs and dagga. He knew nothing about illegal digging. “I just packed the car and went to see what was happening,” he said.

A sparse semi-desert that fills the northern third of South Africa’s West Coast, Namaqualand has been transformed since the discovery of diamonds in 1925. Nearly 70% of the land has been affected by mining, which has fashioned a lunar landscape of barren pits and eroded mounds.

The region’s economy boomed when the diamond industry developed; for the next 80 years mining supported thousands of residents, including the descendants of indigenous Nama Khoi herders who were pushed off their land as mining areas spread.

By the time Yellow arrived, the situation had changed. Facing a stagnating global diamond market and declining resources, De Beers, the largest employer in the region, started retrenching workers in the mid-2000s, shutting its mines after the financial crisis of 2008. In total more than 3 000 people lost their livelihoods. Illegal mining proliferated in response.

Yellow’s status as a bush doctor helped him to access the illicit diamond trade, and he returned 10 times over the next two and a half years to dig. Rastafarian herbalists in South Africa draw on ancient Khoi healing traditions and Yellow’s proficiency with medicinal herbs impressed Nama elders wherever he went. “I was welcomed like a son,” he said.

‘Tough situation’

Our first stop was Steinkopf, a former mission station 50km north of Springbok. A hot wind pressed inside the vehicle when we opened the doors. We were on a dust road beside a row of small, square, grey houses. A woman peered from a dark room. When she recognised Yellow she cried out, stepping into the sunlight. A barefoot man followed her, crossing the blazing earth to the gate. His name was Reuben. He had hollow cheeks and a knotted beard. His dreadlocks fanned out in a triangle, framing his face like a pharaoh’s headdress.

“We were talking about you yesterday,” he told Yellow, inviting us in. His wife Mina nodded. “I can’t believe my eyes,” she said. “It’s like we knew you were coming.”

“We’re here to dig,” said Yellow, after a long round of greetings.

Illegal diggers risk rockfalls when searching for gems on disused mines, such as this one in Namaqualand.

“It’s been tight,” Reuben whistled. “Security got guns, horses, quad bikes now, the whole deal. The situation is tough, elder.”

“Jah guide, but there’s always a way in.”

In the living room a mural of Haile Selassie, the former emperor of Ethiopia who is hailed as God incarnate by Rastafari followers, filled one wall. Yellow rolled a joint and told Reuben about his farming dream when another Rasta, Levi, walked in and lowered himself on to the couch.

Guard duty

Yellow met Levi – a slight, slouching man in his 40s – on his first Namaqualand trip while visiting a friend in the oasis settlement of Pella. A few days after Yellow arrived his friend introduced him to Levi and a few other diggers, and he ended up driving them to the coast the following night.

The men hiked into a disused mining area with three days’ worth of food. Yellow was put on guard duty the first night. The mines, the men warned him, were patrolled by private security companies. If caught, they would be handed over to the police.

Punishment ranges from gear confiscations and trespassing fines of R300 to being charged with the possession of uncut diamonds, which carries a maximum penalty of R250 000 and 10 years in jail.

Yellow watched for approaching headlights while the men worked. They knocked steel pegs into the ground to loosen the gravel. In the morning they sieved and rinsed it. One of the diggers had struck a good seam and picked out eight “pointers” – diamonds smaller than one carat – before stopping to rest. As the men sat around a fire that evening he announced that he was unwilling to share his spoils.

The men began arguing. When they threatened one another with violence, Yellow left.

“I wanted nothing to do with their fight,” he told me. “I caught a lift to my car with another crew. Diamonds made the men quarrel like that. You can’t take diamond energy lightly. It destroys people.”

Incongruous wealth

But in Reuben’s lounge that quarrel seemed forgotten as the men set about planning another dig. We arranged to collect them the next morning and drove on to Port Nolloth, the epicentre of the Northern Cape diamond trade. We arrived to find groups of young men drinking on the promenade. A parade of expensive cars – Renaults, Chevrolets, BMWs – glinted next to them. Port Nolloth has been declining since its heyday in the 1980s, with diamond workers having moved on and fish factories closing; the display of wealth was incongruous with the beat-down look of the town.

We headed to Sizamile, a township at Port Nolloth’s periphery, and Yellow called on former digging accomplices, looking for a place to sleep. Outside one home we met Hamilton, a young Rastafarian from the Eastern Cape. He had arched cheekbones and spoke Afrikaans with a Xhosa accent. He told me he’d been living in Port Nolloth for six years.

“Ah, the Porras been giving terrible prices, elder,” he said, referring to the Portuguese expatriates from Angola who control the town’s diamond black market.

“The prices are better in Cape Town,” Yellow said.

“Ah, but Cape Town is far away.”

Hamilton told us about some diggers who’d recently “hit the jackpot”, unearthing a rich pothole. One of the men had talked, and the next evening people began congregating near the pit.

“The guys who discovered it went in first,” Hamilton said. “They wanted to clean it out. After a few hours they got tired but they knew we were waiting. They just lay on the bottom and slept. My friend wanted to drop rocks on them. We stopped him. He wanted to knock them out.”

The men found 34 diamonds on the first night and 54 on the second, Hamilton said. The discovery was worth millions; a buyer in town paid R200 000 for the lot.

Slow start

The next morning we collected the rest of the crew in Steinkopf. After a slow breakfast and three rounds of ganja the men were ready to leave. The plan was to drive towards Hondeklip Bay, where none of them had worked before, and to link up with diggers who knew the area.

“I know a man in Komaggas,” Yellow said, “otherwise we can ask the Rastas. There are Rastas in Hondeklip Bay, right?”

“Yes, elder, lots,” said Reuben, jumping into the back seat.

Judah, a young man who lived across the street, joined us. He handed me two reggae CDs but they wouldn’t load in the car’s player so he queued up a mix on his cellphone. The men continued smoking as we drove into the desert.

The dirt track south passed through mining territory, stark tailings dumps punctuating the hills. The mines were protected by rusting fences. Thin clouds filtered the sunlight, bleaching the landscape. Excited by the prospect of diamonds, the men opened their windows and began pointing:

“That gravel – big stones in there.”

“Jackpot in that chalk seam, elder.”

“Plenty diamonds in that pit.”

Reliant on illicit trade

Two hours later we reached a tiny, isolated town 40km from the coast. Komaggas borders the De Beers diamond fields; hundreds of residents lost their jobs when the mines closed in 2009.

According to the Komaggas advice office, a local non-profit organisation, 65% of the workforce remains unemployed, with many relying on the illicit diamond trade for income.

We circled the empty streets looking for Yellow’s connection. The clouds had lifted and the air felt like a furnace. Some girls in a dusty yard told us the man had left town and directed us further up the valley, where they said some other Rastafarians lived. We found them and were invited in.

Illegal mining boomed along the West Coast after De Beers closed a number of its mines and retrenched workers.

Twelve men were lounging on battered couches and a cement floor. An obligatory ganja pipe circled the room. I left the men to discuss diamonds and stepped into the yard, where a thin horse was scratching its head against a fence post.

Half an hour later the men joined me and we sat on a granite boulder, watching the sunset. Then we thanked everybody and left.

“Did you make a plan?” I asked Yellow in the car.

“Everyone talks but won’t give details.”

“We need a connection,” Reuben said. “Don’t you know anyone else here?” Reuben asked him.

“No.”

Uniformed guard

In silence we returned to the coastal plain, driving into a thick mist. The temperature dropped and the horizon blurred. Judah queued up more reggae. Levi fell asleep. We had entered a restricted mining zone via a back route and encountered a checkpoint when we reached Koingnaas, a former De Beers settlement proclaimed a municipal town in 2009. A uniformed guard emerged from his hut.

“Turn around!” Judah whispered. “No, don’t – too late!”

The guard handed me a clipboard and I filled out my details. Spades, hammers and pegs filled the boot. A second guard peered through the vehicle’s back window.

“They’re looking at our equipment,” whispered Yellow, watching in the mirror, but then the boom gate lifted and we were inexplicably allowed through.

Night had fallen by the time we reached Hondeklip Bay, a fishing community and former mineworker town at the southern edge of the mining territory. Spotlights on tall poles shone weakly through the gloom. The houses were dark and there were few people on the streets. Two women appeared from the shadows and Reuben lowered his window.

“Sisters, where are the Rastas?”

They looked confused.

“We’re looking for the ayas,” he tried again. “Dreadlock Rastas.” They shook their heads and hurried away.

‘Rasta youths’

Thrice more our inquiries were met with blank looks and suspicion, but then a man in a Blue Bulls jacket directed us to a compound on the outskirts of town. Reuben and Judah climbed out to investigate.

“Rasta youths inside,” Judah reported when they returned. “Good vibrations. They say they have diamonds.”

The room was hazy and blue. Two dreadlocked boys were frying potatoes on a hotplate. They stood and greeted the men, incanting Rastafarian praises. The other boys – there were 10, none of them dreadlocked – sat silently until the ritual was over. They made space for us and we squeezed in. We drank coffee and the men asked questions about diamonds, which the boys evaded, and a few hours later most of them departed. Only the two young Rastas remained. They shared their meal with us and pulled out a spare mattress. Yellow left to sleep in the car, and, two to a bed, we passed out.

Spades, steel pegs and hammers are the tools of the trade.

The next morning we hung around, waiting. The two youths were not from Hondeklip Bay, it turned out, but had hitchhiked 115km from Leliefontein, a village of fewer than 1 000 people in the Kamiesberg Mountains. They were looking for diamonds and didn’t know where to start. Their room belonged to a Namibian digger, they told us.

“He was working last night. He knows the area well. Maybe he’ll help you,” they said.

‘Little alternative work’

I left the group and walked to a fish and chips restaurant in the harbour, where I met a former mineworker, Sam Cloete. The tables were empty and the fryers in the kitchen were cold. Cloete, a greying man in a faded purple T-shirt, was alone.

“I opened this shop with money from my retrenchment package,” he told me. “I worked for Trans-Hex from 1983 until 2001, when they closed the mine. A hundred and sixty people lost their jobs. I worked for De Beers afterwards but they shut down a few years later. I’ve done okay, though. My wife is a teacher. It helps.”

He stood to greet a visitor, who said he was just looking, then sat again, resting his hands on the table.

“It was a tragedy when the mines closed. A lot of people were in debt and had no other income. There’s little alternative work – some fishing and kelp harvesting, a small abalone farm. Most people are employed by public works. A few men work on the mines up in Oranjemund. I’ve been lucky. I can’t complain.”

“And those who couldn’t find jobs?” I asked. “Are many people involved in illegal digging?”

“Yes,” he said, “but I don’t know much about it. Certainly there are people who take chances. When they go digging they say they’re going to the bank. One spot is called ‘Absa’; another is called ‘FNB’. You can make money but it’s dangerous. I’m 68 years old. I’ve had a good life. It’s not worth taking the risk.”

Eight years

The Namibian digger was sitting with the men when I returned. He had scarred knees, a scarred forehead and scarred cheeks. He told me he’d been digging in Namaqualand for eight years. “Come and see my diamonds,” he said.

We followed him to a zinc house and waited while he made a phone call.

A few minutes later a bald man in slippers arrived. He frowned and shut the gate.

“Who wants to buy?” he asked.

The mood grew tense. Reuben stepped forward.

“Brother, we’re from Steinkopf. We’re on a digging mission. We came to see how things work here.”

“They aren’t buyers,” the man spat, turning to the Namibian.

“We’d like to see your diamonds,” Yellow said.

He hesitated before pulling out a roll of bank packets.

“Thirty-six stones,” he said, “all smaller than a carat. You don’t get bigger diamonds in Hondeklip.”

“How much do you want for these?” I asked.

“R18 000.”

When it became clear that we were only there to ask questions, the man became agitated again and we left.

‘Gangster’

“I didn’t like him,” Yellow muttered as we walked away. “He was a gangster – a 26. Did you see his tattoos?”

“And he was talking nonsense,” said Judah. “There’s plenty big stones around here. I know it.”

That evening a teenager in overalls who’d been hanging around all afternoon produced a pakkie of his own. A single diamond the size of a dried lentil shone through the clear plastic.

“I found it near the beach,” he said. “Diggers wash their gravel there at night.”

In the sparse semi-desert of the Northern Cape, opportunists dreaming of riches sift through the abandoned diamond fields for ‘pigeon eggs’ – elusive stones weighing five carats or more.

He had acne scars and his eyes were glazed from smoking a bottleneck.

“What’s your price?” Judah asked.

“R500.”

“I’m going to offer him R200 and some ganja, elder,” Judah whispered to Yellow when the kid walked away. “I can sell that stone for R700.”

He called the boy back and the rest of us dispersed. It was twilight and fog was moving in.

Diamond deal

I stood back and watched the pair speak. The kid handed Judah his packet. Judah unfolded two banknotes and dug in his pocket for the marijuana. They bumped fists to conclude the deal – the only one of the trip.

I returned to Cape Town the following afternoon, leaving Yellow behind in Port Nolloth. He told me he wasn’t coming home without a packet. Two weeks later he called me from Retreat.

“I didn’t get anything,” he said. “Security was too tight.”

“Are you disappointed?”

“Not really. Look, I wanted some nice stones. You know how important my mission is. But the diamonds are still there. I’ll get my pigeon eggs next time.”