Safa president Danny Jordaan was chief executive of the tournament's local organising committee.

Former directors on the board of the 2010 World Cup organising committee and the South African Football Association (Safa) executive committee are sure to be sweating somewhat now that allegations of corruption, centring on the diversion of $10-million intended for the 2010 event, have come to light.

Already two high-ranking South African officials have been identified by the FBI, although they are only known to the public as co-conspirators #15 and #16. But for the others, who were appointed to play an oversight role in the lead-up to the World Cup, they are likely wondering how well they did their jobs and who will carry the can.

A company search this week shows the tournament’s local organising committee, registered as a section 21 (nonprofit) company, had a grand total of 31 directors, including the likes of Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene, African Union chair Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, ministers Jeff Radebe and Susan Shabangu, former Cosatu general secretary Zwelinzima Vavi, media tycoon Koos Bekker and prominent lawyer Michael Katz.

The then Safa president, Molefi Oliphant, was also a director. Irvin Khoza was the committee’s chair, and current Safa president Danny Jordaan was its chief executive.

South African law says directors of companies can be held personally liable if they have not fulfilled their duties adequately. The Companies Act requires a director to act in good faith and in the best interests of a company.

Where a decision is taken, the director is required to have taken steps to become informed about the matter and must have a rational basis for believing that the decision was in the best interests of the company.

Last Wednesday, a case was brought by the United States government against 14 former Fifa officials on 47 counts of alleged bribery, racketeering, money laundering and fraud over two decades. On the same day, six of these Fifa officials were arrested at a Swiss hotel.

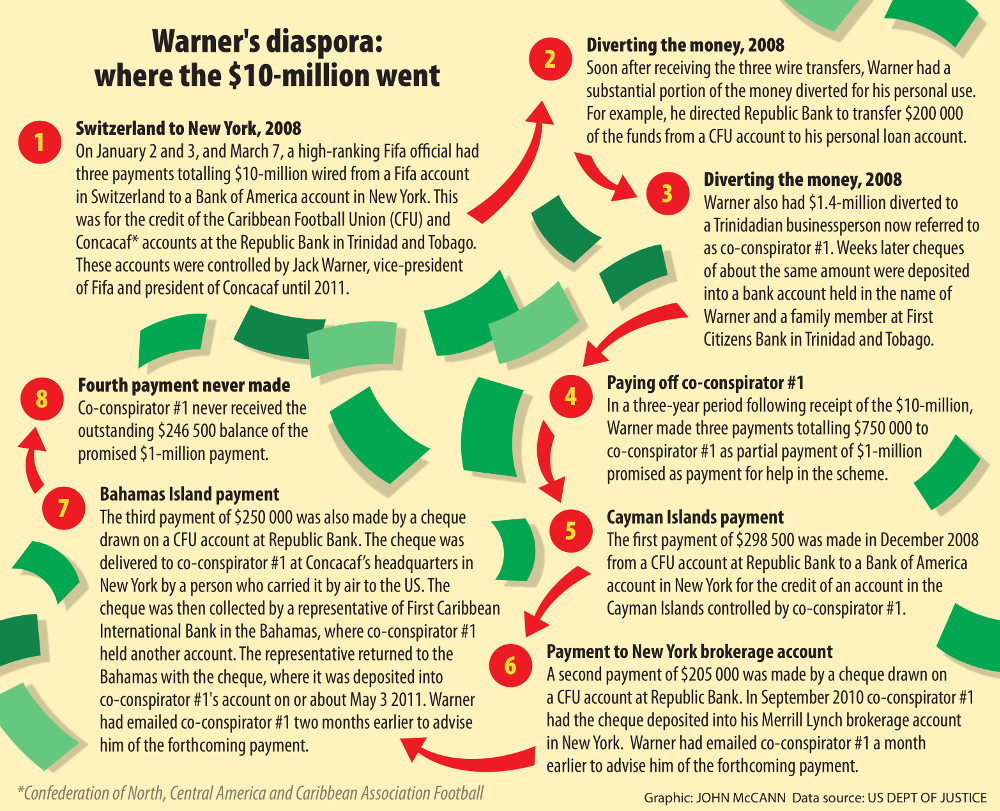

Central to the investigation, led by the FBI, are payments in 2008 amounting to $10-million. This money was intended for South Africa’s 2010 World Cup local organising committee, but was instead diverted on the instruction of Oliphant.

A leaked letter sent from the Safa president (on a Safa letterhead) to Fifa asked the football body to withhold $10-million from the organising committee’s future operational budget funding to finance the Diaspora Legacy Programme – to be administered directly by Jack Warner, a Fifa official and president of the Confederation of North, Central America and Caribbean Association Football (Concacaf).

According to the US indictment, the money was transferred to accounts in the name of Concacaf. The South African government and Oliphant have confirmed that this money was indeed part of a diaspora legacy programme.

The programme, the government says, was formed to share the benefits of the 2010 World Cup with the African diaspora through funding to develop football.

But these accounts were controlled by Warner who, the indictment alleges, “caused a substantial portion of these funds to be diverted for his personal use”. This week Warner arrested, but soon released on bail of $395?000. He has strenuously denied the allegations against him

The indictment alleges that these payments in 2008, as well as a briefcase filled with cash in 2004, were part of the corrupt transactions that secured South Africa’s bid to host the 2010 Fifa World Cup.

The recipient of the letter was Fifa secretary general Jérôme Valcke who, according to reports by the New York Times, citing an anonymous source, is said to be responsible for the transfer of $10-million into the Caribbean accounts. Fifa has denied this and insists the payment was authorised by its late finance committee chair, Julio Grondona.

A number of local organising committee (LOC) directors, including Nene, didn’t respond to questions about their oversight role as directors. Of those approached, only Vavi responded: “I can’t remember the LOC board approving the letter [of] the then Safa president to make that donation. I can’t recall seeing that in the financial statements. I am very keen to see the conclusion of the investigations.”

Katz referred questions to Khoza, the committee’s chair and current Safa vice-president, who did not respond to emailed questions.

Safa spokesperson Dominic Chimhavi said the dealings of any World Cup are between Fifa and the local football association, Safa in this case. “The president of Safa has blanket power. He consults, but at the end of the day he is the one who writes and signs the letters.”

The local organising committee, he explained, reported to Safa at the time. Asked whether the Safa national executive committee would have then have been informed of funding decisions relating to the committee and the diaspora legacy programme, Chimhavi said: “Yes, they had sight of it.”

Speaking at a press conference on Wednesday, Minister of Sport Fikile Mbalula said the local organising committee no longer exists – “it has been disbanded” – and that the so-called organising association agreement was between Fifa and Safa and not the local organising committee.

Indeed, the agreement stipulates that the local organising committee was to be established by Safa and “shall be and remain an internal, fully dependent and controlled division of the host national association”.

Furthermore, the contract states the organising association (which pertains to the local organising committee and Safa) is subject to the control of Fifa, which “has the … final decision power on all matters relevant to the hosting of the championship”.

The organising association was obliged to submit progress reports to Fifa and was subject to inspection. Budgets had to be sent to Fifa and the organisers were obliged to keep “complete, clear and accurate books”. Safa and the local organising committee were obliged to provide all financial and other information to Fifa, with an audited financial statement including a profit and loss statement.

According to the sports department’s 2010 Fifa World Cup country report, the 2010 Fifa financial report reported that Fifa had received audited financial reports on the transfer of funds to the organising committee for every year up to 2009 and its operational expenses amounted to $516-million.

“While the overall costs exceeded the original budget, these were covered by higher revenue from ticket sales, resulting in an unanticipated profit of $10-million. In other words, Fifa covered all of the organising committee’s operational expenses,” the report said.

The 2010 Fifa World Cup Legacy Trust, which was formed after the event and continues to administer funds for legacy projects, lists Valcke among its directors.

At Wednesday’s briefing, Mbalula reiterated that the $10-million was above board and part of a diaspora legacy programme. He noted that a further $70-million had been paid over for projects to improve soccer in other African countries.

The minister said that the South African government could not account for what happened to the money after it was paid over.

He would not comment on the allegations of a briefcase filled with money in 2004, describing it as something from the movies.

In a guilty plea later on Wednesday, former Fifa official Chuck Blazer said that from 2004 to 2011 he and others on the Fifa executive committee agreed to accept bribes “in conjunction” with the selection of South Africa as the host nation for the 2010 World Cup.

Paul Hoffman, director of the Institute for Accountability in Southern Africa, said, although directors need to satisfy themselves that the financials of any company are in order, “for the stuff on the balance sheet there is an innocent excuse for it. But the suitcase of money is off the balance sheet altogether.”

Regarding the $10-million in diverted funds, Hoffman said “one couldn’t really call it a bribe because by then we had already landed the bid. So there was no inducement involved … It doesn’t mean it’s not a corrupt payment; it just means it’s not a bribe.”

Hoffman said the place where the purported corruption comes in is in “the suitcase full of hard cash”.

He said pleading ignorance would not be a smart strategy for directors of the local organising committee or members of the Safa executive committee. “If I were advising them, [the line would be] the African diaspora fund was regarded as a worthy cause; a good way of showing solidarity for those in the diaspora who did not get a direct benefit from the World Cup. So as a show of goodwill, $10-million was deducted,” he said.

Of the 31 directors of the local organising committee, four resigned in 2005, four resigned in 2009, 18 left in 2010 and three, including Jordaan, were the last to be active. Nene joined in 2009 and resigned in 2010.