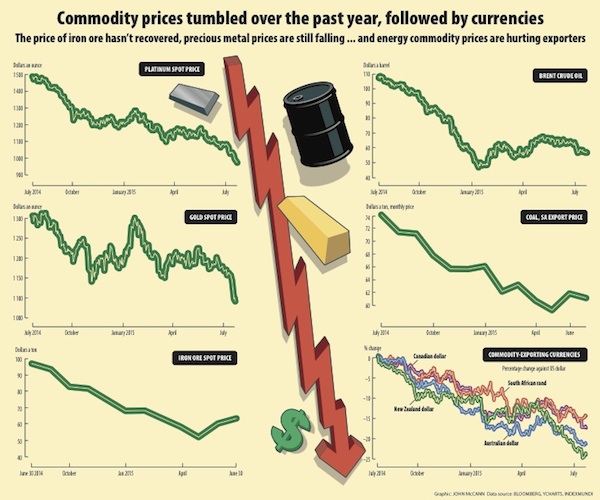

The latest slump in raw materials has been led by a sell-off in gold

The global commodity price collapse is deepening amid weak demand and anticipation of an interest rate hike in the United States, and has dragged down mining shares in recent days.

The Bloomberg Commodity Index of 22 raw materials, from silver to gas, has plunged to its lowest since 2002 following faltering demand in China.

The latest slump in raw materials has been led by a sell-off in gold, which this week saw its longest decline since 1996.

And Goldman Sachs’s Jeffrey Currie believes the worst is yet to come. He and others say prices could fall below $1 000 an ounce for the first time since 2009. This week the gold price slumped below $1 100 for the first time in five years.

“With the more positive outlook on the dollar, and with debasement risk starting to fade, the demand to use gold as a diversifying asset against the US dollar becomes less and less important,” said Currie, who told investors to sell in 2013, before the metal’s biggest collapse in the past three decades.

The rout is deepening amid mounting speculation that US interest rates will climb this year, curbing the appeal of bullion because it doesn’t pay interest as competing assets do. At the same time, China bought less of the metal than analysts were expecting, and the dollar keeps getting stronger.

The price is putting the squeeze on some of the world’s largest gold producers, not to mention those in South Africa that are in the midst of wage negotiations in an attempt to broker a deal that will sustain this sunset industry.

“In the longer term, we definitely like playing this market on the short side,” Currie said. “We think we are in a structural bear market, not only in gold but across the commodity complex, because the individual commodity stories are reinforcing to one another, creating a negative feedback loop.”

Iron ore and steel industries have also been a major casualty of the slowdown in China. For South African operations, not even the weak rand has eased the pain.

ArcelorMittal South Africa has applied for a 10% import tariff on certain steel products to stem the damage at home. But it has proved too late for the likes of Evraz Highveld Steel, which this week announced that it has decided to cease production at its steelworks temporarily.

‘This was necessitated by, among others, working capital constraints and reduced domestic demand in steel, mainly due to a significant increase in Chinese imports. All plant and equipment will be placed in curtailed operations mode and prepared for future start-up,” the company said in a statement, which also announced a proposed restructuring process that could see half of its staff let go.

Anglo American subsidiary Kumba Iron Ore, which released its interim report on Tuesday, said its headline earnings had fallen 61% in the six months ending in June.

Kumba has also issued a notice that it is considering restructuring at its Thabazimbi mine, which supports 800 employees and 360 contractors but is less profitable than its Sishen operation.

The iron ore price has hit Anglo American hardest. The mining giant is expected to take a write-down of billions on its Minas-Rio iron ore assets in Brazil. The company warned the write-down could be as much as $4-billion and that it is likely to cut its dividend for the first time since 2009.

The company took a write-down of $3.9-billion in February.

BHP Billiton also anticipates a write-down of about $2-billion against its US shale assets, which have been severely affected by the ultra-low oil price. Its spin-off company, South32, which houses all BHP’s former South African operations, has pre-tax impairments of $1.9-billion on the value of its manganese and coal operations.

South32, the world’s biggest producer of manganese ore, last month delayed the planned restart of three ferromanganese furnaces in its Samancor venture with Anglo in South Africa, and flagged a potential write-down.

The slide in commodities prices began with the steep decline in the oil price that, in January, saw a barrel of Brent crude dipping to about $50 – its lowest level since 2009. It appeared to be recovering in the following months, getting near $70 in May, but has since lost ground and this week dropped back to $56 a barrel.

The latest downturn in the world oil market could mean that Russia’s recession will stretch into next year for the longest slump in two decades.

Paced by oil’s rebound of more than 40% from a six-year low in January, Russia looked to be nearing the trough of its first slump since 2009. But crude’s faltering recovery in recent weeks has raised questions about government assurances that the economy will return to growth in 2016 and it is further squeezing a budget already on course for its widest deficit in five years.

Russia, which Dutch multinational ING Bank NV estimates needs oil at $80 a barrel to balance its budget, will endure a two-year economic contraction if crude prices remain at $60 through to 2016, according to the central bank.

Reeling from a currency collapse last year and sanctions over Ukraine, the government has already cut budget outlays by 10% and dipped into one of its sovereign wealth funds to cover the shortfall.