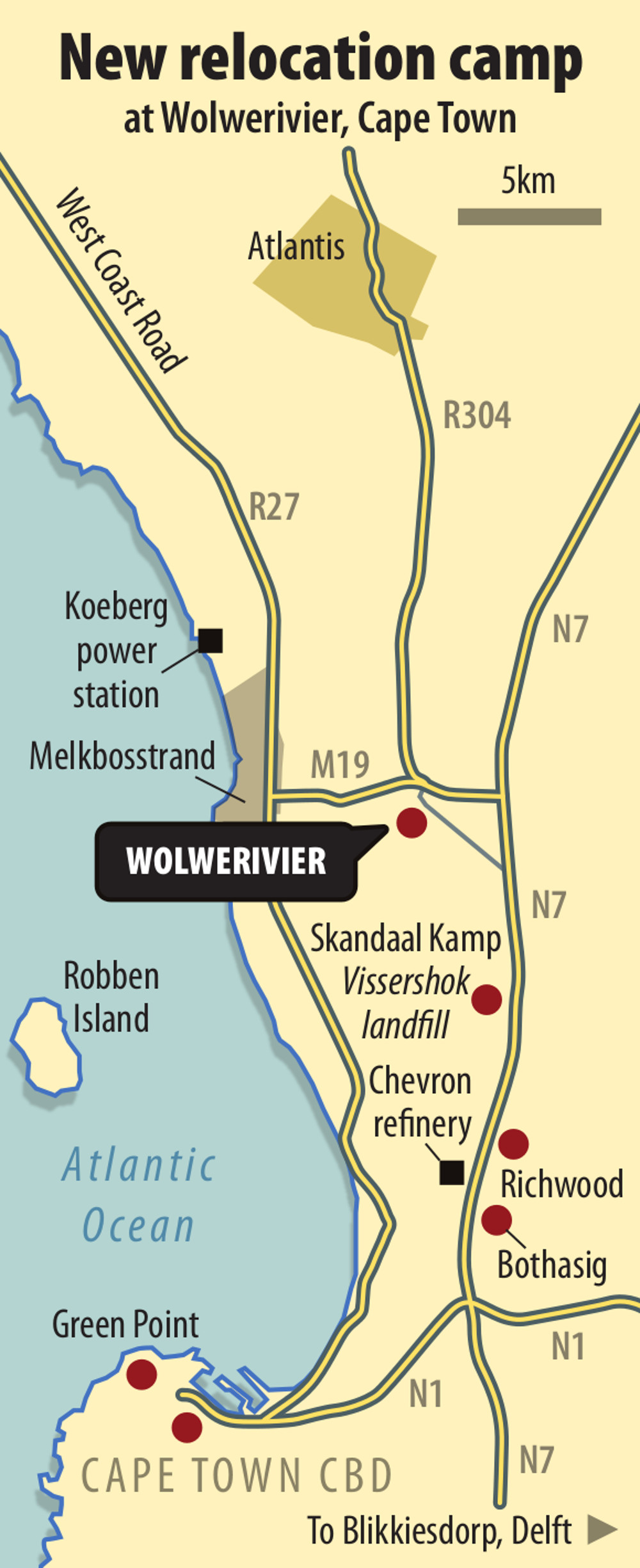

The Wolwerivier 'temporary' relocation camp is about 35km from Cape Town.

Four hundred and sixty-four squat sheet-metal structures. A gravel precinct. That is all. This is Wolwe-rivier, Cape Town’s newest relocation camp for poor families who have been cleared off land in the name of development.

The allure of the city – the hope for jobs – the reason many of them have migrated to the Western Cape, remains now permanently distant in the hazy view of Table Mountain 35km to the south. Unlike other post-apartheid relocation areas, fancifully conceived by local governments as “temporary” solutions for poor evictees, Wolwerivier is unequivocally permanent.

In closer proximity, 17km to the north, lies Atlantis: the apartheid state’s failed urban experiment of contriving a self-sustainable district for black working-class families – or Cape coloureds – who could not be arrested and trucked from the city to Bantustans in the Eastern Cape.

The industry that was supposed to employ and sustain Atlantis’s families faltered and closed shop almost as soon as it was established. But the people have remained, scarred by decades of violence, substance abuse, rape and chronic unemployment.

In the past decade, relocation areas in the likeness of their 20th-century predecessors have re-entered municipal planning paradigms in South Africa’s major cities.

More sophisticated models

Over time, the models for these camps have become more sophisticated – Wolwerivier is built with “superior” materials, and the sites are better serviced and conceptually framed by a more thoughtful public relations exercise from the City of Cape Town.

But the experience of peripheral abandonment, food insecurity and poverty, both in means and in opportunity, remains as the motif linking Wolwerivier and its new “urban poor” inhabitants to the forcibly resettled camp communities of apartheid.

The City of Cape Town metropole says the distance of the camp from fits with its urban reintegration policy because a new city, to house 800 000 and on transport routes, will be built nearby. (Photos: David Harrison, M&G)

Desmond Hoffman (47) is new to street life. Wolwerivier, the new housing solution, has played a major role in bringing that upon him. Spend a weekday afternoon in Cape Town’s suburb of Bothasig off the N7 just outside the city, on the edges of the middle-class white suburbs, and you will find him.

For a decade Hoffman lived on the fringes of Bothasig in a shack, in the Richwood informal settlement near the Chevron oil refinery. During that time a network of dustbins, scrap recycling, work in white families’ gardens and handouts brought in the food to provide for him and his life partner, Siena Erasmus.

A former domestic worker, Erasmus is today incapacitated by arthritis. She lives in a transitory shack on the Wolwerivier farm. Since they were removed from Richwood on the eve of a storm in July last year, she has been waiting for a padlock and a key to one of the structures. In the meantime, she survives on food parcels sent by Hoffman and carried by friends from Bothasig once or twice a week.

“As God is my witness, I am dried now only by the wind,” he tells me one afternoon. He offers his clothes for touch, as though the proof of the wetness lies in the fact that they are now dry. Three layers of clothing. He smiles. The irony is not lost on him.

Winter storm

The previous night saw a Cape winter storm of biblical proportions. The city authorities sent out an early warning for vulnerable families to brace themselves – dig trenches, move to higher ground, unblock storm-water drains.

Hoffman must have missed the memo. As the cold front rolled in sheets of rain from the South Atlantic to make landfall on the peninsula, he was drinking heavily.

“You find your place, somewhere where they will not find and kill you,” he says, not for the first time conjuring these bogeymen in describing his new, timid street identity.

“And then you find your drink and you must take it all – because you will fall right there. Your insides must be warm or you won’t make it through. The night is cold. Sometimes it is wet. But if you have your plastic … if you are warm inside and somewhere else in your mind, you can forget and survive.”

It was more than the lack of opportunity that drove him back towards the city. Life in Wolwerivier became an exile more alienating than the rain, the skarrel (scrounging) and the more acute drunkenness of life in the gutters of Bothasig.

Yet for a weekend drink, a shower, a bed and the company of Erasmus, he will return to this place of exile.

“What can you do?” he asks with a shrug.

Proximity to jobs

The predicament of Hoffman and many others in Wolwerivier is not new, either in Cape Town today or in South Africa’s history of eviction and relocation. The sudden removal from the proximity to jobs has always been central to the destitution of relocated people.

Look under bridges in the Cape Town city centre. There, in tarpaulin tents, huddled around fires or scrubbing pots, you will find them too.

“That is where you’ll find Blikkiesdorp,” says Jerome Daniels of the Blikkiesdorp Joint Committee.

Angeline ‘Liena’ September rents a portion of a structure in the Wolwerivier camp.

These folks are part of the diaspora of Gympie Street, of the greater Woodstock area and Sea Point – evicted from their homes to the peripheral Blikkiesdorp relocation camp in the name of market-led “regeneration”, “development” and “improvement”.

As Bothasig is for Hoffman, the streets of the city centre are the only place where many from Blikkiesdorp can regain any semblance of their livelihoods and lives before being evicted.

Watershed moment

This month, with lightning speed after months of slow anticipation, the City of Cape Town moved about 250 families from Skandaalkamp – another community of subsistence farmers and rag pickers living off the Vissershok landfill site – to Wolwerivier.

Their relocation is a precondition for a planned extension of the dump site but, in the city’s view, it is also an opportunity for some of Cape Town’s poorest people to move to a better and cleaner living environment.

Brian sits outside his home and says he won’t go to the relocation site.

In the mainstream media, the move went almost unnoticed. Yet for the affected families, and for the city’s planners and its human settlements directorate, it was a watershed moment. Dozens of trucks carted away people, furniture and clothing. Many pets were left behind – there was apparently no space for them. Of the 300 structures in a settlement that has defiantly grown and existed in one way or another since the 1970s, many were torn down and torched as residents retreated to their new homes.

The efficiency of the move’s execution was amazing. Community leaders expected a slow transition over several weeks. Four days after the first trucks arrived, Skandaalkamp lay in ruins – with half-packed suitcases strewn about, structures broken, dogs picking through the rubbish and sniffing at the corpses of their fallen peers, and a thin film of ash covering everything.

Structure size

Five kilometres away, in her new shack in Wolwerivier, community leader Thozama Qobongwana sits preparing a list of houses that have more than one household, or up to three generations of the same family, living in them. The size of the city-built structures, considering the numbers of people they would inevitably house, had been her most enduring concern during the months of negotiations with the municipal human settlements department before the move.

These negotiations, she says, were defined by inequity and intimidation. Comply and do not break ranks, or you will be removed and left with nothing: this appears to have been the city’s unofficial message.

Noxolo Mnani’s partner is in hospital with third-degree burns after their home in Wolwerivier burnt down.

Her appeals were never heard, Qobongwana says, and the result has been groups of adults and children, as many as 10 in number, sleeping in structures of just 24m2 in size.

In one such home, Liena September (33) gives a tour of an empty floor, pointing out the arrangement according to which she, her husband, two other adults and six children turn in for the night.

Another home nearby lies gutted by fire – the result of an exploding paraffin stove in a household where money and appliances to make use of the prepaid electricity boxes are elusive. Noxolo Mnani (31) lost everything she owns in the fire, as well as her new home. Her partner and the household’s breadwinner, Lindikhaya Kaba, lies in Tygerberg Hospital with 70% of his body covered in third-degree burns.

Such nuances were never thought through in the conception and building of Wolwerivier, says Qobongwana. To avoid the risk of fire in the home, Skandaalkamp had many makeshift shelters standing apart for open-flame cooking.

Desolation

But the real concerns do not lie in the floor size, the stifling red tape that regulates extensions to the structures, the lack of streetlights, the dysfunctional electricity boxes or the myriad promises about the quality of the structures that never materialised.

It is Wolwerivier’s desolation that will be people’s undoing, Qobongwana predicts.

“We’re only four days in and already people are getting hungry,” she says during the Mail & Guardian‘s visit earlier this month. “People do crazy things to one another when they are hungry.”

Portable toilet refills wait to taken to the relocation camp.

The fact that the nearest supermarket is far away has seen the inflation of prices at the only spaza shop on site. In Wolwerivier, some of Cape Town’s poorest people are paying more for basic foodstuffs than almost anyone else in the city. An apple, complains resident Manuel Thys (52) as he forms a tiny fist to illustrate the fruit’s size, costs R4.

Add to this the limited job prospects and the lack of hospitals, recreation facilities or schools for kilometres in any direction – that is the reality for the people of Skandaalkamp, Rooidakkies and other areas to follow: Takkegat, Spoorlynkamp and Richwood.

“What good is a new toilet if you have none of these things?” asks Brian Verwey, who went to court to fight an eviction from Richwood, and lost. That land, too, is earmarked for development. For him, it was the second time he had been evicted from there. The first was in 1985.

“It is like being shot by the same arrow twice – once under the Boere and once today.”

‘Deliberate creations’

Nineteen eighty-five. In that year, the Surplus People Project published a seminal study of forced removals in South Africa. Throughout, but especially in the chapter on relocation areas, voices from poor and evicted people echo through the decades to chime in with the experiences of Verwey, Hoffman and Skandaalkamp’s relocated residents.

Intermittently, the authors return to the privileged white communities and government policies that underpinned these peoples’ removals from their well-located shacks and homes.

Of relocation camps, Laurine Platzky and Cherryl Walker write: “Poverty and suffering anywhere are to be challenged – but what makes poor conditions in relocation areas especially unacceptable is that they are deliberate creations of government policy … [These] were planned by government experts: deliberately sited miles from any centre of employment, designed as residential settlement(s) only and abandoned to the people who were forced to move there.”

Abandonment. Walk through the sterile green and white rows of Wolwerivier’s settlements today and few words could better describe the impression one is left with.

The state’s efficiency in moving hundreds of people over a single weekend has not been matched by any efforts to assist with the resident’s longer-term transition, remarks Qobongwana bitterly.

Shifted responsibility

Indeed, the City of Cape Town, in introducing Wolwerivier to the public by a media statement in October, shifted the bulk of responsibility for helping with the adjustment.

“The Western Cape government is looking into the longer-term transport, educational and health needs of this community,” said then mayoral committee member for human settlements Siyabulela Mamkeli, in a fleeting reference to the challenges faced by people existing on the urban periphery.

Recent queries to the four relevant provincial departments to corroborate and request a progress update over the past 10 months went largely unanswered.

Western Cape education spokesperson Paddy Attwell was the only one to respond, saying that the department will “assess specific needs as the project proceeds”.

When the new school term started three weeks after the relocation, Qobongwana received a message that the old school bus has not been diverted from its regular route to include the children now living in Wolwerivier. On the first day of the new term, Wolwerivier’s children found their own way to school.

Marked by difference

As modern relocation areas are marked by their continuity with the apartheid era, so too are they marked by difference. Difference, because today it is difficult to find the policy underpinnings for their continued existence and proliferation. They exist not because of policy, as was the case when Platzky and Walker were writing, but in spite of it.

For in the new South African state’s overhaul of a national urban agenda, as in new metro-municipal spatial development frameworks, the reintegration of poor urban residents that were previously ejected and confined to the periphery is a central objective.

The contradiction of relocation camps in this policy environment was noted by the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions in its 2008 report on Durban’s housing crisis. It is true of Cape Town, where attempts are being made to redress old spatial imbalances, an urban edge has been introduced to contain the sprawl of fringe development akin to the fragmented apartheid city, and local politicians bemoan the legacy of crude segregationist planning in areas such as Atlantis and Khayelitsha.

“Apartheid spatial planning left many in Atlantis completely disconnected from economic opportunities,” Cape Town mayor Patricia de Lille told Business Day in March. “The socioeconomic effects of this have been dire. They have experienced high unemployment [and] high crime rates, and they have also had to battle with the scourge of substance abuse.”

Yet the city doesn’t consider Wolwerivier to be poorly located. The metropole’s West Coast component, which is currently farmland dotted with beach towns such as Melkbosstrand, is a “growth corridor” for the future. It “holds the potential for integrated, inclusive communities close to transport routes and employment opportunities”.

Wescape megaproject

The city’s vision to realise this potential is called Wescape: a planned, self-contained megaproject that will be 31km2 in size, R140?billion in cost and designed to accommodate 800 000 of the city’s residents over the next few decades.

These are grand solutions. But, as some of the University of Cape Town’s top town planners warned in an open letter to the mayor and Western Cape Premier Helen Zille in 2013: “Cape Town has had its fair share of these – Atlantis, Mitchells Plain, Khayelitsha – and all have been abject failures.”

Verwey and Wolwerivier’s other inhabitants know this. They require no confirmation from academics. Their mutual histories bear witness. So, too, does an awareness of themselves, in the eyes of the state, as “surplus people” once again.

“We know why the city has chosen there [Wolwerivier] for us,” Verwey says. “No tourist or influential person will ever drive that side road [to Wolwerivier]. No government would want others to see how we must live.

“You cannot raise a child under those circumstances, outside of all society and hope. Such a child will be an outsider for all of his life. He will have no hope.”

Daneel Knoetze is the urban land justice researcher at Ndifuna Ukwazi and a freelance journalist.