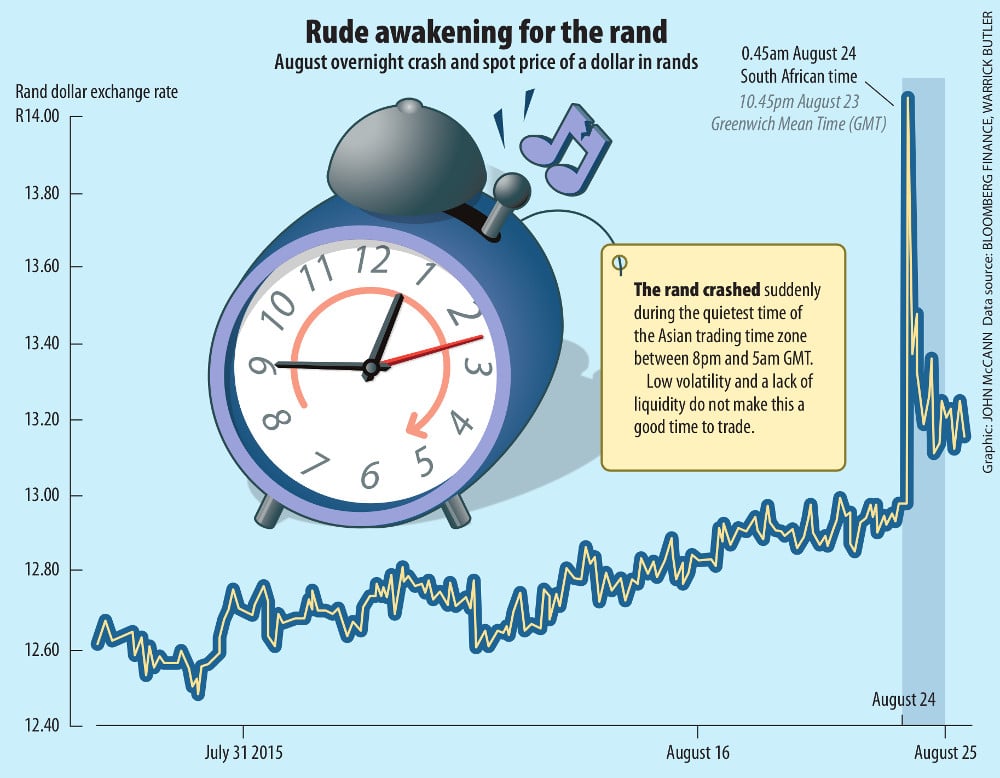

In the ungodly hours of Monday morning, for a fleeting moment the rand fell to R14 to the dollar, its lowest level in history. Although Standard Bank trader Warrick Butler was wide awake – having received a call from the bank’s Asian time-zone trader minutes earlier when the rand was heading towards breaching a key threshold – he missed the historic moment because he decided to take a quick shower before rushing to the office. By the time he’d rinsed off the suds, it was all over.

Although the next two trades, a few minutes later, were back down at the 13.67 level, the news headlines that morning told of the unprecedented weakening of the currency amid general gloom in the global economy.

Butler said there was no real market-shaping event to explain the rand collapse of more than 5%. The event was less likely a result of market forces, and almost certainly a system error, probably exacerbated by automated trading platforms with algorithms “designed to panic”.

Butler came to this conclusion while standing in his lounge, and asking five questions of Standard Bank’s Asian time-zone trader: Are the S&P 500 futures getting hammered? Are United States Treasuries trading massively stronger? Is gold trading higher? Are the safe haven currencies, the Swiss franc and yen, both stronger against the dollar? What are the emerging market Asian currencies doing?

The negative answers revealed that the market was not in a total risk averse frame of mind, and the rand weakness was not part of a larger global phenomenon. This made the matter more puzzling.

Most rand trade does not happen during Asian trading time and so most parties who have rand commitments prefer to wait for the Johannesburg or even the London market to open because that is where the majority of liquidity is concentrated, said Butler.

Michael Keenan, South African strategist at Barclays Africa, said the rand’s pricing is a lot fairer during the liquid periods.

One illiquid trading period is the Asian trading time, and another is during US trade and can create a lot of volatility, he said.

Trading skewed in favour of the London trading session as a result of big change in the forex-currency market after 2008’s credit crunch and the rise of electronic trading.

Butler said: “Laws like [Wall Street’s] Dodd Frank Rule have curtailed speculative trading from banks using their balance sheets whilst Basel III increases the overall cost of capital allocated to each investment.

“There is now a significant cost involved in holding on to highly volatile assets due to the capital allocation requirements.”

To combat this increase in costs, banks have turned to electronic offerings to manage their Forex flows – instead of having specialised emerging market traders, they can now just plug their requirements into a pricing aggregator to automatically hedge out risk.

“Not many humans are left in the market. Those that are left are by and large short on experience or interest and face a market that moves at the whim of a computer,” said Butler. “The consequences have at times been catastrophic, however.”

This system has allowed for the entry of high-frequency trading systems – automated trading systems used by large investment banks. These systems can identify and conduct trades far quicker than any human could, said Butler, but they are “designed to panic” because they always need to get out at the next best price.

“These systems are designed to sit in front of the best bid and offer in order to be the first price traded. If the spreads are wide, as they are in most illiquid emerging market currencies, their models try and capture every bid and offer paid by various institutions once the market settles into a pocket of liquidity. This allows them to capture all the risk spread without actually taking risk, as the banks do and therefore create a kneejerk reaction in price.”

He said the flaw in the high-frequency trading programme is if they are to maximise profitability they need to stick their hands in many, many jars. This allows them to internalise as much as possible but also allows them an exit point (automated “stop-loss” trades) should things go wrong.

“There aren’t just one or two HFT’s [high frequency traders] out there. There are many, and when they need to close out a position they fall all over each other trying to get to the exit door.”

This is probably what happened on Monday morning when the rand hit its historic low. “On Monday, in very illiquid conditions, Asian traders put in an order to buy some dollars and it took the rand up from 13 to 13.40 to 13.70, and then 14.07. The next trade was at 13.67,” said Keenan.

Although detailed information on what happened is not available, Butler said some assumptions can be made based on what was available during that time zone, and what tools a trader would have had at their disposal. He offers an example of how the rand’s momentary slide could have happened.

Keenan argued that more than one trade was required to establish a new exchange rate.

“The traders I speak to are not treating 14.07 as the high. They think it was basically a miss-hit in the market, based on the fact that it only traded there once. So I would not agree with reports that we reached an all-time high. The all-time peak remains 13.84 back in 2001.”

Even the South African Reserve Bank (Sarb), usually tight-lipped on currency concerns, put out a statement on Monday to register its unease about excessive volatility, but reiterated that it is committed to the exchange rate of the rand being set by market forces.

It did, however, indicate that it would be willing to become involved in some ways.

“In the event of developments that threaten the orderly functioning of markets or that may have financial stability implications, the Sarb may consider becoming involved in foreign exchange markets to ensure orderly market conditions,” the bank said. Keenan said he thought the Reserve Bank’s statement had been taken out of context in media reports. “I don’t believe they are going to intervene. In 1998 they tried to do it. And it hurt a lot.” However, “I would have thought there would be some sort of mechanism in place to have stopped this [the miss-hit] from happening. In Wall Street, if the market moves more than 8% on the day, trading stops to assess the reasons for it. So there are circuit breakers in the system.”

Keenan said the Reserve Bank could get involved by providing liquidity during illiquid periods. “They could leave an order in the system, on actively traded platforms, so when the rand gets to a certain level, they will buy some dollars.”

Said Butler: “By the Reserve Bank saying that [it would get involved] is probably verbal intervention as it is. I’m hoping that’s as far as it goes. If they started messing with the exchange rate there will be a lot of unhappy international investors.”

The central bank could instead work with others around the world to “whittle out some of the HFT noise”, he said.

And it’s R14 to the dollar in an eye-blink

No one knows what really went down in the moments when the rand breached 14 to the dollar on Monday morning.

But Warrick Butler, head of rand and emerging markets trading at Standard Bank, said that experience tells him it may have happened something like this:

- A Japanese trader must buy about $150-million to $200-million in exchange for rands – a fairly big order during this trading time zone – in a five-minute fixing window and they would have an array of electronic currency networks or aggregator systems he or she can use to execute this transaction.

- In the five minutes before the fixing price, the trader lines up all the liquidity at their disposal and starts to accumulate dollars to fill the total transaction value. On a normal day this will not be an easy job, says Butler, and in Asia it is almost mission impossible.

- Some of the counterparties that the trader has bought dollars off are the high-frequency trading systems – automated trading systems used by large investment banks.

- They get paid and immediately they put in a bid through other systems to try to buy those dollars back.

- But now there are a few high-frequency traders that are sitting in the same position. Suddenly their bid is no longer the best bid in the market and they start an electronic bidding war through the various portals.

- The Japanese trader may still be left with a residual position that they were not able to cover in time. They, too, are left fighting the machines for any available dollars left in the market.

- Offers (the supply of dollars) dry up and bids to exit the respective positions keep being laid one in front of the other – and R14 to the dollar trades in the blink of an eye.