Lessons on lost knowledge

To re-examine the format of art exhibition reviews, we asked University of the Witwatersrand school of arts education lecturer Rangoato Hlasane and three of his postgraduate education students to discuss Mawande ka Zenzile’s exhibition, Mawande ka Zenzile, within the framework of their curriculum.

Hlasane challenged the students – Matshediso Matla, Bianca Stevens and Bianca Jacquet – with a comment by Walter Mignolo, who has published extensively on semiotics and literary theory, on the limits of and opportunities presented by the notion of “artists’’ and “art works’’ regarding decolonisation:

“First, you start from etymology. What does ‘art’ mean? It means ‘skill’. It was a translation from the Greek ‘poiesis’ to the Latin ‘ars’. So a shoemaker and a carpenter are artists and poets, in the sense that they are ‘makers’. The question is, when does poiesis become ‘poetics’ and ‘art’ become ‘artistic’ (for example, artistic work of art)? Poeisis needs a particular executioner, the poet that is able to, instead of making a shoe or building a house, ‘make’ a narrative that captures the senses and emotions of a lot of people.”

Hlasane asked the students: “When we enter this space constructed by ka Zenzile, which modes of working, material and languages do we encounter? What are the histories of these modes and languages and material culture/s?’’

Iingcuka ezambethe ifele legusha

My mother and my grandmother

Matshediso Matla

Ka Zenzile’s work evokes nostalgic memories – lessons on the use of cow dung with my grandmother to cover holes in the mud house. On the farm, most mud houses relied on cow dung as one of the key building materials. Cow dung is used to break conventions of the Western use of paint on canvas and to oppose the Western stereotypes of what constitutes art materials.

How do we define modes of art? Who has the “right” to define those modes? Whose histories of art are made visible?

Heritage of a Noble Man, the maize-grinding stones in the exhibition, resonates with the knowledge of my upbringing and my family histories: “tshilo le lwala” symbolised by the two stones, and “impepho” (Helichrysum species burnt as incense)used to communicate with the ancestors.

The fact that the work is presented in broken pieces represents our cultural knowledge that has been lost, ruined or forgotten because of the Western experience imposed by our education systems, especially the institution of higher learning, which ignores our knowledge, our heritage and our cultures.

Most of what is taught to us in tertiary institutions are Western forms of art that claim the status of high art. This status assumes a superior position to our “African” art. The curriculum decides what can be perceived as art.

Ka Zenzile’s work speaks volumes in relation to what is happening in higher institutions today.

Reading Heritage of a Noble Man, the broken stone and scattered yellow dried maize symbolise absence. Yellow maize is used during extreme drought.

Drought can signify the yearning of life (rain) and cultural freedom. It can question gender roles because the objects used were/are mainly used by women, not men.

But the title speaks of a noble man, someone with high moral principles. The fact that the artwork appears in the picture as complete stone, but in reality at the gallery appears broken can be read as: “our” heritage is kept in books and research outputs that were not done by “us”, but in reality it is ruined by the “noble” man.

It is not there

Bianca Stevens

He picked up the knot that had been

tied 81 times

It carries information and histories

and reflections on experiencesIn the mind the mind is the boat

I take it with me wherever I go carrying cargo

Taken to another country to work for the greater good you will be valuable a true gem for his work

Gets nothing, what? I said he gets nothing with the sorry he gets.

The boat must be built!

He still cannot untie the knot

He is not like his father

Four times you say Sor … Sor … Sor … Sorry

Black man sit down white man sit down white man is standing

… this is imperial power sit down,

Black man stand up

Both are standing power is equal

No!

I am not your slave

I’m sorry

Not for the things,

… I said

Not good enough

I said I am sorry

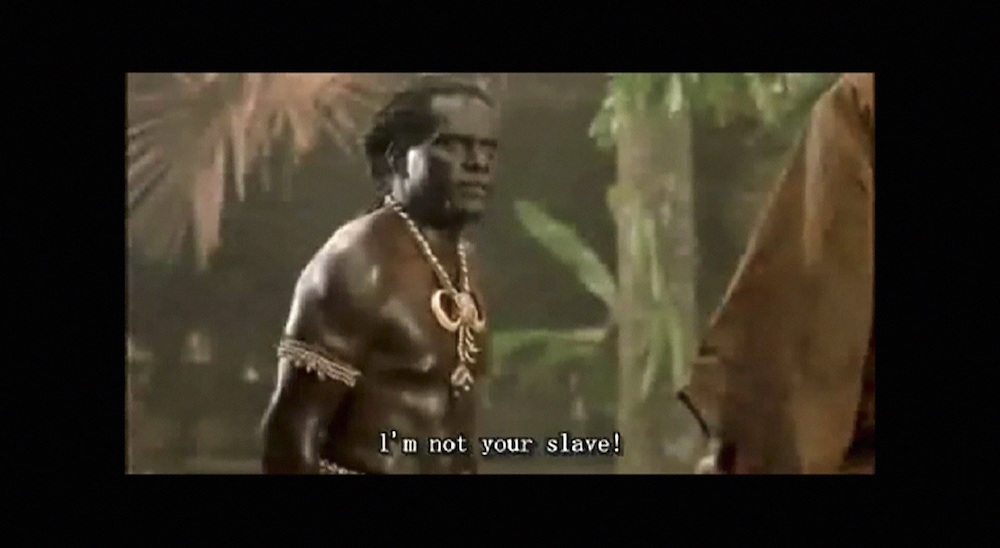

Ka Zenzile’s video, Imbongi yo-mntonyama, depicts a black male and a white male on an island. There is a powerful moment in the video where the black male stands up to tell the white male that he is not his slave. He repeats this 81 times. The white male says “sorry” four times.

The repetition is used for emphasis, almost as if conditioning the black male to claim back his identity. He starts off saying “I am not your slave” at a moderate speed, then it builds up faster. The faster it goes the squeakier it gets, imitating the tone of a young boy. The squeakiness in his tone and the repetition stresses his refusal to inherit the slave mentality.

Conversely, the white man’s “apology” is not good enough because no amount of words can take back the legacy and impact of slavery imposed on black people.

Imbongi yomntomnyama

Memories of youth

Bianca Jacquet

The work that caught my attention almost immediately was one of a little boy sitting on a pedestal. The pedestal is painted black, questioning the gallery/museum/university histories. The boy (who is painted black) wears a school uniform. The uniform appears to be new, whereas his school shoes appear well worn, synonymous with an experience, intergenerational inheritance and of struggle. He also has a hessian bag/material around his head, with a rope tying the bag/material down. He has one hand in the air, reaching out. In his lap is a revolver. The title Iingcuka ezambethe ifele legusha alludes to youth.

The pedestal could be referencing (Western) histories of education and knowledge.

Education professor Michael Young challenges the notions of knowledge of the powerful versus powerful knowledge, and who decides on which/whose knowledge and experience is important.

This alludes to another work in the exhibition Call a Spade, a Spade. Here the notion of elders reprimanding and infantilising youth entered the conversation.

Is the opinion/knowledge even experience of the elders’ more or less important than that of the youth? The outstretched arm is a pleading for help from the viewer. Who is this viewer?

This work references two other works at least: the three hanged men on the ground floor as well as in self-defence (which the boy has his back turned to). It depicts a boy in uniform lying on the ground pointing a gun at a man who is standing over him. The painting is mostly blacked out and can only be made out vaguely.

Next Chapter and Iingcuka eza-mbethe ifele legusha could be read together: one as a “memory” of the event (a murder) and the other as the child on trial for a murder (hence the sentencing sack cloth?)

Mawande ka Zenzile is on at the Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg.