Limpopo’s more wealthy schools will be forced to increase tuition fees drastically next year following a decision by the provincial education department not to supply textbooks any longer.

Principals of quintile four and five (fee-paying) schools, including former Model C institutions, were informed in a letter by Ndiambani Mutheiwana, acting head of the Limpopo education department, on May 26 that they could only use 40% of the funds they receive from the department to buy stationery and textbooks.

One Limpopo principal, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals, said his school’s fees would have to go up by almost 50% next year to cover the cost of buying textbooks. “We will have no option but to increase school fees if the department insists that quintile four and five schools must buy textbooks. We are bound to spend over R2-million — which we don’t have in our coffers — for next year on textbooks.”

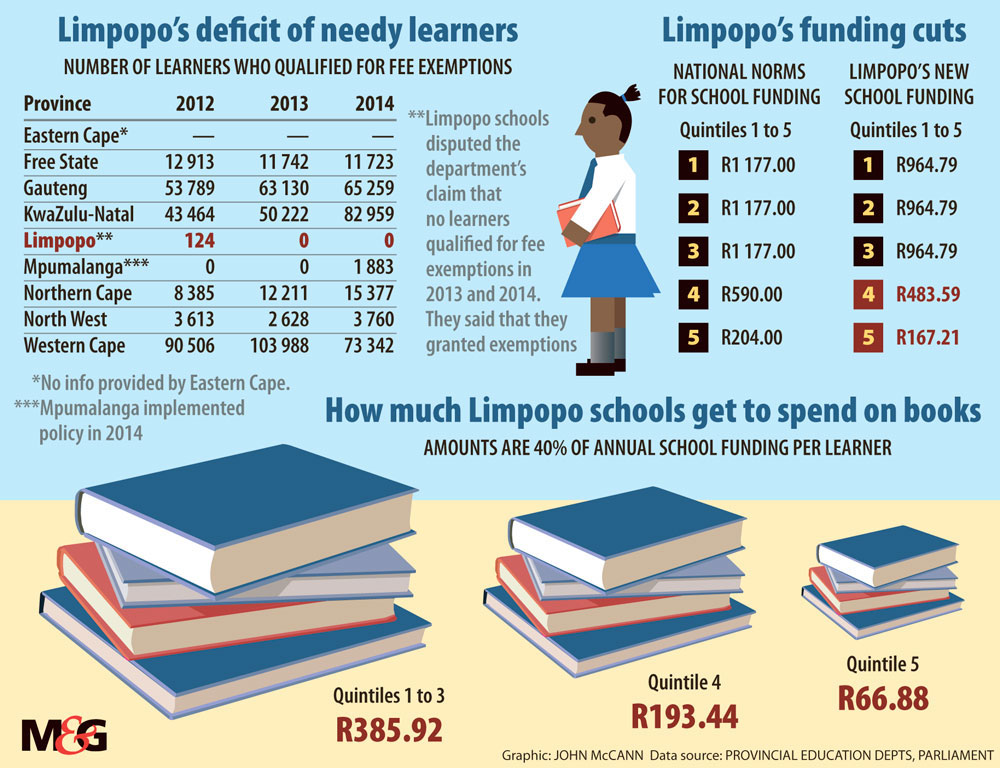

Quintile four and five schools charge fees, whereas quintile one, two and three schools do not. Quintile one refers to the “poorest” schools and quintile five schools are the “least poor”. According to the national norms for this year, provincial education departments were expected to allocate R1 177 for every child attending a quintile one, two or three school — the poorer schools. The amount allocated per learner drops to R590 for a quintile four school and R204 for a quintile five school.

But not all provincial education departments adhere to the national norms. Limpopo’s education MEC, Ishmael Kgetjepe, announced during his budget speech in April that quintile four schools would receive an allocation of only R483.59 for each child instead of R590, and quintile five schools would get R167.21 instead of R204.

This means a quintile four school would be able to spend only R193.44 (40% of R483) per learner from the state’s allocation on textbooks, and a quintile five school would be allotted a miserly R66.88 per learner for this purpose.

In contrast, the department earmarked R596‑million to buy stationery and textbooks for learners in no-fee schools.

“I can’t feel happy because this [the nonsupply of textbooks] is going to have a very negative impact on our school. It’s the department’s responsibility to supply LTSM [learner-teacher support materials] to schools, not the responsibility of schools,” said the Limpopo principal.

The department did not realise that his school has had to write off about R200 000 in school fees this year as a result of exemptions granted to disadvantaged learners, he said.

Unlike other provinces, schools in Limpopo that grant fee exemptions have not received any compensation from the department, he said. “The department thinks quintile four and five schools are collecting more money from parents; that’s why they took the decision that we should buy textbooks for ourselves. But our school is not charging a high fee.”

Another headmaster said his school fees would go up by 15%, adding: “If I have to buy seven textbooks per learner at a cost of R150 per textbook, it will cost the school more than R1.1‑million. Quintile four and five schools that don’t have the money will really be in trouble.” His school granted fee exemptions totalling R3.3‑million this year to about 245 learners, he said, adding that he expected a further 100 parents to apply for fee exemptions next year if fees were hiked substantially.

Limpopo education spokesperson Naledzani Rasila said he was not aware of the department’s decision to stop supplying textbooks to quintile four and five schools.

“What I know is we started distributing books to all schools in the different quintiles towards the end of last year. I am not aware of any schools that didn’t receive it.”

The province made headlines in 2012 after learners went without textbooks for the first seven months of the year.

Meanwhile, principals at some schools in Eastern Cape, including no-fee schools, said this week that their learners were still using photostat copies of textbooks because books had not yet been delivered, despite orders being placed last year.

The principal of a school in King William’s Town said its budget was being depleted because teachers were forced to use reams of paper to make copies of literature setworks for schoolchildren to use.

“Teachers make a batch, which they take to their different classes. The child doesn’t go home with a textbook in some subjects.”

Edmund van Vuuren, the Democratic Alliance’s education spokesperson in the Eastern Cape, forwarded a list of 1 725 textbooks that were outstanding in 23 subjects in grades eight, nine and 10 at Jeffreys Bay Comprehensive High School to the province’s education MEC, Mandla Makupula, in April.

Van Vuuren confirmed that learners were still sharing textbooks, adding: “Children cannot take books home because, in a lot of instances, teachers keep them in the cupboards because of the shortage of books. We can’t be surprised when our results are not what it should be.”

The Eastern Cape education department failed to respond to questions.

All 785 of the fee-paying schools in the Western Cape that ordered textbooks in June last year, for this year, received them in November.

Last Friday was the cut-off date for schools in the province to order textbooks for next year. Western Cape education spokesperson Paddy Attwell said the deadline for ordering textbooks had been brought “progressively forward” over the past three years.

He said schools could order textbooks using the department’s online ordering system and had to pay for them from the allocation they received from the department.

“We can’t afford to buy new books every year for every subject and grade. It’s essential that learners and parents co-operate with schools to ensure the success of their textbook retrieval programmes.” The department spent R605‑million between April 2011 and March 2014 to provide eight illion textbooks and reading books. He said schools now had to maintain these stocks by “topping up” to meet increasing demand and to replace lost and damaged books.

Unlike Limpopo, which stipulates that only 40% of its allocation to schools must be used for textbooks, Gauteng schools can use half of their allocation for this purpose.

The Gauteng education department insisted that the funds it gave to fee-paying schools for textbooks were sufficient. “These schools are fee-paying and, as a result, they can sustain themselves. Allocation is just supplementary to these schools.”

This despite the fact that 65 259 pupils attending fee-paying schools in the province in 2014 qualified for fee exemptions, resulting in a chunk of income being lost.

Fee-paying schools in KwaZulu- Natal can use 60% of the funds from the department to buy textbooks.

This means that a quintile four school could spend R313.20 per learner on textbooks this year and a quintile five school R107.40.

The provincial education department said limited finances determined the allocations. “The issue at hand is not whether the department believes that the allocation is sufficient. National policies are clear on this matter.

Quintile four and five schools are fee-paying and they are empowered to raise additional funds. These schools therefore have additional financial resources that can be utilised for purposes of LTSM [learner-teacher support material] procurement as and when necessary.” At least 1 031 fee-paying schools in KwaZulu-Natal, including 713 that are responsible for buying textbooks themselves, will be purchasing them for next year through a central procurement process that is managed by the department.

North West’s education department said its 34 fee-paying schools had received their full quota of LTSM for this year, but that it did not buy textbooks for each learner every year: “We only buy textbooks on a top-up basis. Additional textbooks are only procured to address shortages caused by increased enrolment or lost or damaged books.” — Prega Govender