September 1966. The body of Dr H.F. Verwoerd

On September 6 1966, parliamentary messenger Demitrio Tsafendas stabbed South African prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd to death in Parliament, in front of many witnesses. Before he could be put on trial, Tsafendas’s sanity had to be ascertained as early encounters with officials had placed a question mark over his mental capability.

Tsafendas was defended by advocate Wilfrid Cooper, and the ultimate judgment was that Tsafendas was insane and unfit to stand trial. He therefore avoided the death penalty that would surely have followed a proper trial. He was detained by the state on death row in Pretoria Central Prison until 1994, when he was moved to a mental home. He died in 1999.

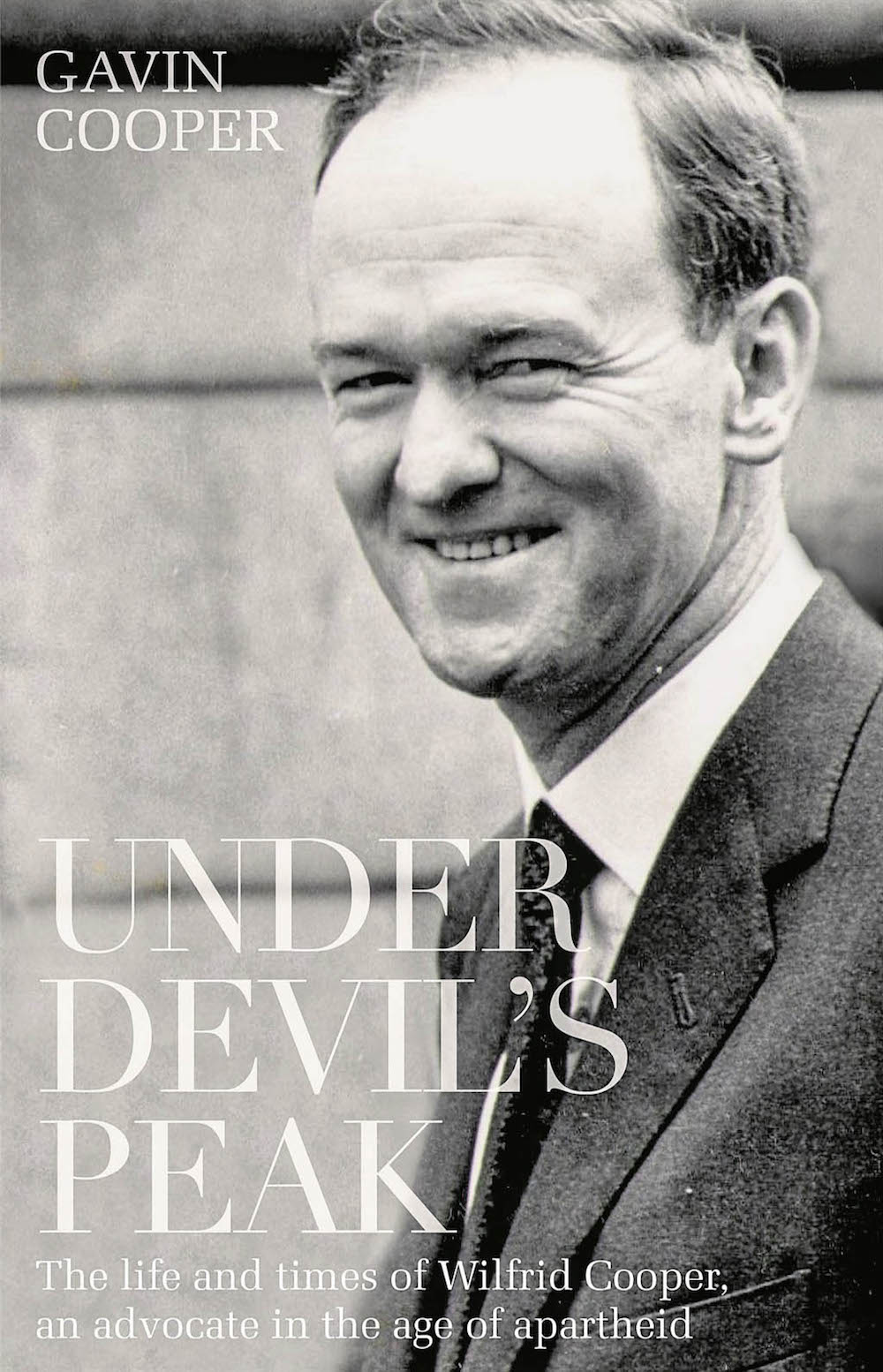

This edited excerpt is taken from Under Devil’s Peak by Wilfred Cooper’s son Gavin. Besides dealing with Cooper’s career, which involved defending political prisoners and inquests into deaths in detention, the book considers what was called “the trial of the century” in South Africa, as well as the question of whether Tsafendas really was mad – and later responses to the enigma of the assassin.

Wilfrid Cooper believed that, although Demitrio Tsafendas did not intend it and nor would he have foreseen it, the assassination of Hendrik Verwoerd was of immense political importance for South Africa. It was equal, he believed, in its consequences to the assassination of John F Kennedy for the United States.

Wilfrid Cooper believed that, although Demitrio Tsafendas did not intend it and nor would he have foreseen it, the assassination of Hendrik Verwoerd was of immense political importance for South Africa. It was equal, he believed, in its consequences to the assassination of John F Kennedy for the United States.

The man who had championed with granite-like conviction and invincible self-righteousness the vision of grand apartheid was dead. With him went the rigid belief that South Africa could be unscrambled into separate ethnic states, and even though Verwoerd’s successors tried to hold back the tide of change, in the end they were forced to adapt and then give way.

Verwoerd’s assassination was a defining event for the generation of which I was part: ever afterwards we could remember where we had been when we heard the news that Verwoerd had been killed. His grandiose funeral drew an estimated quarter of a million people, who lined the streets of Pretoria to view the cortège, an event only surpassed by the funeral of Nelson Mandela in December 2013.

The three weeks leading up to the trial had involved Wilfrid and his team in a monumental amount of work in defending their client. When it ended in their favour, they were elated that, despite public pressure, justice had been done and their client would not stand trial to face the death penalty.

In 1996, when interviewed by the Cape Times for his 70th birthday, Wilfrid recalled of Tsafendas: “He was a messenger in the Houses of Parliament and was indigent. It was apparent to me he was insane; he was also highly religious, intelligent and articulate. The killing of Verwoerd was a symbolic killing, like St George slaying the dragon. It was not political. Tsafendas was rejected from the word go. During his adolescence he developed a tapeworm and this became his “dragon” – he was ruled by it. I believe he realised that he had travelled everywhere but went nowhere. And there was Verwoerd, the highest in the land, in contrast to his simple position.”

In October 2013, close to the 47th anniversary of the hearing into Tsafendas’s sanity, a member of the Eastern Cape provincial legislature, Christian Martin, wrote to the National Heritage Council requesting that the graves of Tsafendas and Verwoerd be declared heritage sites. “Dimitri [sic] Tsafendas and Hendrik Verwoerd changed the course of post-war South African history more than any others, when Tsafendas stabbed to death the ‘architect of apartheid’,” he wrote.

It was Martin’s opinion that homage should be bestowed on Tsafendas, a hero and martyr for the cause of the South African people. The heritage council ejected the request, stating that “it is important to realise that history and heritage are not the same thing”.

In life Tsafendas was seen as neither black nor white; Judge Andries Beyers saw him as a “meaningless creature”. He was not recognised as being a freedom fighter because his actions were deemed personal and not political, and the court found him to be mad. Helen Suzman said of the murder of Verwoerd: “I thought we were rid of one of the worst scourges we had.” She had no doubt that Verwoerd’s death profoundly affected the course of South African history and set it on a path to democratic elections in 1994.

In life Tsafendas was seen as neither black nor white; Judge Andries Beyers saw him as a “meaningless creature”. He was not recognised as being a freedom fighter because his actions were deemed personal and not political, and the court found him to be mad. Helen Suzman said of the murder of Verwoerd: “I thought we were rid of one of the worst scourges we had.” She had no doubt that Verwoerd’s death profoundly affected the course of South African history and set it on a path to democratic elections in 1994.

But besides Martin’s attempt to memorialise Tsafendas, there appears to have been little effort made by the current government to remember him, and the major post-apartheid histories of the ANC barely mention him in passing. Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom has only one reference to Tsafendas, as “the obscure white parliamentary messenger who stabbed Verwoerd to death, and we wondered at his motives”. In the Thabo Mbekiinspired The Road to Democracy series, a history commissioned to address “the paucity of historical records chronicling the arduous and complex road to South Africa’s peaceful political settlement”, there is scant reference to Tsafendas; it merely refers to Verwoerd’s assassination by “an official messenger, Dimitriou [sic] Tsafendas”.

A review of the fate of Tsafendas does, to my mind, invite the question why it is that the actions of the slayer of the architect of apartheid, who was incarcerated for decades in a manner that can only be seen as a gross violation of human rights, were never investigated in detail by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Why was Tsafendas relegated to a mere contextual reference? Was it that the TRC took heed of Chief Justice MM Corbett’s words? Corbett said: “Tsafendas was brought to trial, and on overwhelming medical evidence declared by the court to be mentally disordered and therefore unfit to plead. The suggestion that the case should be ‘reviewed and investigated’ is, with respect, pointless and absurd. To view him as a ‘victim of apartheid’ is, in my opinion, bizarre.”

Did they wish to avoid having to investigate what is common currency, that he was insane? Or was it that they wished to avoid a Gordian knot: that Verwoerd was possibly the victim of a political murder, the act being camouflaged by the plea – and convincing behaviour – of insanity?

In my research into my father’s life, and particularly into this key individual in both his career and the historical trajectory of South Africa, I have found the contemporary perspective on Tsafendas to be nothing less than an enigma. I was perplexed when I read in two works by an eminent history professor that his name was inscribed on the Wall of Names at Freedom Park outside Pretoria – and then found this to be apparently untrue.

The wall was erected under the Mbeki presidency as a poignant tribute to the many lives lost in various global conflicts in which South Africans have fought, including the liberation struggle; to me it would make sense to include Tsafendas in this roll call.

When visiting the Wall of Names prior to the publication of Under Devil’s Peak, my wife and I spent more than an hour searching in vain for the name of Tsafendas. The chief curator of the park, Victor Netshiavha, confirmed his absence, though he couldn’t immediately check his database because of a system failure.

Several days later I received an email from the park’s research manager, Tlou Makhura: “Our records indicate that the name Dimitrio [sic] Tsafendas was submitted to Freedom Park, together with 44 others, on a list titled Deaths in Pretoria Central Prison [in] September 2011. The name, together with 44 others, was verified by the names verification committee at a workshop held on September 28 2011.

“The [committee] resolved that the name, together with 44 others, did not have enough biographical information to enable the process of verification and approval for inscription on the Wall of Names at Freedom Park. The entire list of 45 names, including the name of Dimitrio Tsafendas, was deferred to subsequent names verification workshops, with the proviso that further research to provide fuller biographies of the 45 names be conducted before the resubmission of the list.”

So it seems there are others who consider it appropriate that the name of Verwoerd’s assassin take its place, carved in stone, alongside those of Steve Biko, Mapetla Mohapi, Imam Haron and the many others who gave their lives in the low-intensity war that was the struggle against apartheid. That he is considered someone who died “in Pretoria Central Prison”, when he in fact died while institutionalised at Sterkfontein mental hospital, and that the committee considers the biographical information available on him lacking, are two further curiosities to add to the enigmatic, history-changing life of Demitrio Tsafendas.

Though his status in contemporary history remains in limbo, what is certain is that he assassinated the architect of apartheid, the only South African prime minister to have died in such a manner.

For the final words on the matter here, I defer to journalist David Beresford, who wrote extensively on Tsafendas and sadly died the month before the publication of this book: “During that 1966 hearing on the sanity of Tsafendas there was a particularly piquant exchange between his counsel and Mr Justice [Andries] Beyers. The judge president asked: ‘Did the accused tell you that history will judge whether he was right in killing the deceased?’ [Psychiatrist] Dr [Harold] Cooper SC replied: ‘I do remember him saying something to the effect that history will prove whether he is right or wrong.’

“A madman, or a man with a mission? Perhaps Mary Shelley came closest to summing up the life of Tsafendas, with the words she put in the mouth of Frankenstein’s monster: ‘Am I to be thought the only criminal, when all humankind sinned against me?’”

Gavin Cooper is a businessperson. Under Devil’s Peak is published by Mercury and distributed by Jacana. See Burnet Media for more information.