Paul Simon with Bakithi Kumalo at the Montreaux Jazz Festival in 2008

The year 2016 seems to be slouching to some kind of morbid end. Commentators with a claim to progressive persuasions everywhere are making Orwellian prognoses for the world on the back of a spectacularly divisive election win by Donald Trump in the United States. It is not unlike the year 1986. Only then the gaze of the world and the US were trained on a South Africa reeling from a dystopian condition.

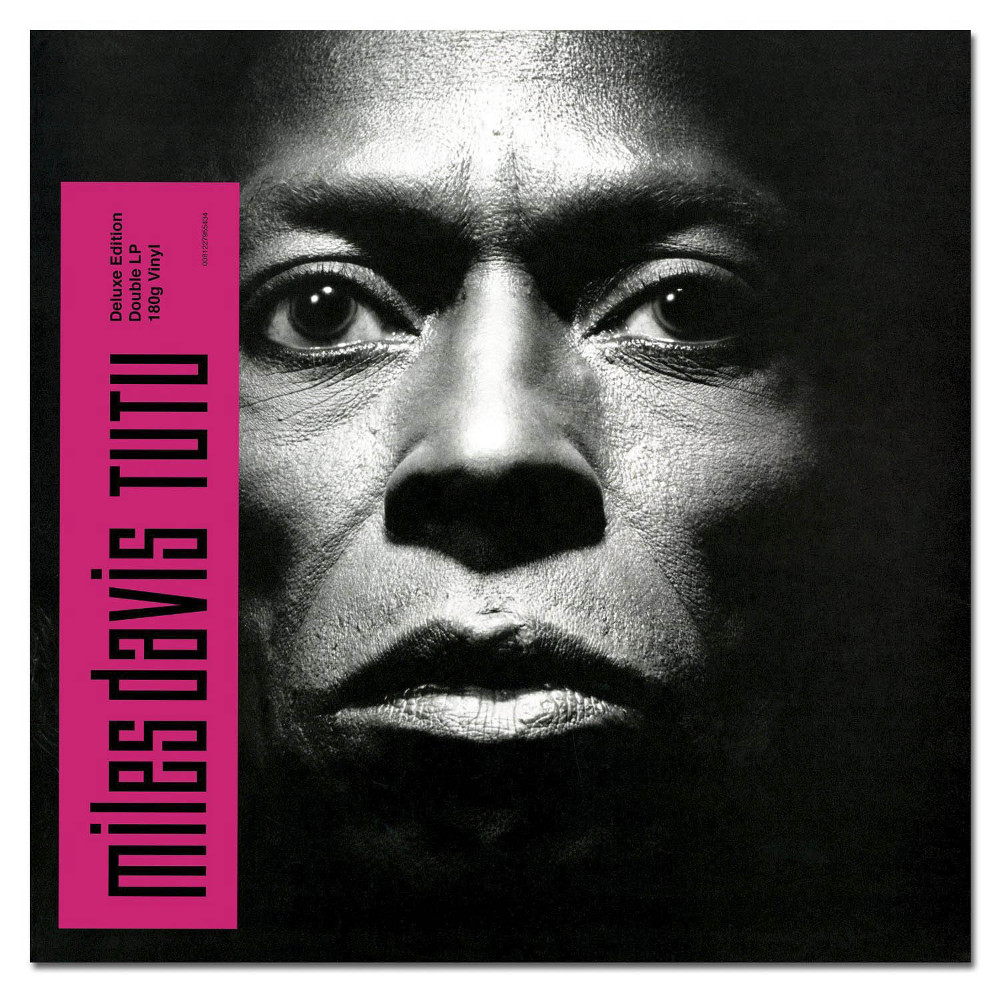

Two historic musical records were released that year, giving voice to a nervous condition. Miles Davis released the last of his epoch-marking masterworks, Tutu. Davis’s Tutu was a grand musical ode to the people of South Africa and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who had just been installed at St George’s Cathedral, Cape Town. He became the first black person to head the Anglican Church in South Africa.

The other was Graceland by Paul Simon, a collaborative breakthrough that angered the freedom movement as much as it helped to propel its mission to end oppression in South Africa.

Graceland was an unlikely masterpiece, co-created by the American singer-songwriter on a creative gamble. To begin with, he visited the land of apartheid in defiance of the US-sanctioned cultural boycott in 1985. The ANC and artists against apartheid were outraged. Simon was seen by some to be legitimising a discredited state. Simon was desperate to revive his waning musical career. He’d been battling depression following a divorce and the failure of a previous record. Then his creative impulse was whetted by a bootleg cassette tape of South African music.

The music he made with an army of South African musicians would not only launch their global careers but also would call the world’s attention to a dying apartheid.

Hit songs such as Diamonds on the Soles of her Shoes and Homeless helped to launch Ladysmith Black Mambazo, now a global musical phenomenon. Bakithi Kumalo’s bass guitar wizardry on You Can Call Me Al gave him an international career too. He would move to New York on the back of the success of the Graceland tour.

Part of the breakthrough of Graceland was that Simon toured with South African musicians performing their own original music alongside their collaborative work. Ray Phiri and Stimela, Tau Ea Matsekha, the Gaza Sisters and the Boyoyo Boys were some of the great South African musicians who blew the lid off apartheid isolation on the back of the album.

Propulsive percussive textures of Tsonga music, the polyrhythmic charge of mbaqanga and the quasi-tonal harmonic language of isicathamiya became a healing tonic to the world on the brink. By July 1987, Graceland had sold more than six million copies worldwide — the highest sales release at the time since Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

Davis, the prince of darkness, had South Africa on his mind too. The genius trumpeter had recently returned to playing music after his legendary five years of silence. He was recovering from the effects of heavy drug use, fast living and a hip replacement operation.

Jazz music was struggling for relevance in world of changing tastes. Davis was on a hunt for an existential breakthrough — just like oppressed South Africans who were getting even bolder in their pursuit of freedom. It was the year after the state of emergency and PW Botha’s Rubicon speech.

Political lobby platforms organised by African-American politicians and civil society bodies, such as the Congressional Black Caucus, were also pushing hard against the evil-enabling financial relationship between the US and apartheid South Africa. They won the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act, which became public law on October 2 1986.

Davis was awake to these developments. The tone and texture of his music would, as always, reflect the times. This he achieved not only in theme but also in style and form.

Unlike his earlier masterpieces, which were created live with a band, Tutu was created using the latest technological toys by producer and bassist Marcus Miller. Then only 27 years old,

Miller’s heavy use of synthesisers, sequencers and drum machines upset a lot of jazz purists. It sounded nothing like what many loved about the aging trumpeter’s classics.

Miller says, in the bio-doccie directed by Mike Dibb: “Tutu forced people to take sides. I had people come up to me to say: ‘Man, I loved that album. It changed my life.’ Other people would say: ‘Man, you ruined Miles Davis’s career!’ It was fantastic to me because that’s how it was supposed to be.”

It was divisive: loved by many for its embrace of change and hated by just as many for not being like what was known and expected.

But Davis’s genius trumped the naysayers — Tutu and its subject were a triumph.