The Council for Medical Schemes estimates that fraud, abuse or waste accounts for about 15% of the R160-billion in claims that medical aids pay out annually. (Gallo)

Widespread strikes in the agricultural sector in 2012 culminated in a victory – a substantial hike in the minimum wage for farmworkers from R70 to R105 a day. But the jubilation was short-lived and, four years later, many feel they have been hoodwinked.

On many farms there was a trade-off. With every extra rand paid over, the number of boxes a farmworker was expected to fill with fruit increased. In many cases, input costs – such as housing on the farm, water, electricity and transport – have been passed on to the farmworkers. They say the gains from the wage hike were largely negated.

Now that a national minimum wage of R3 500 a month (or R175 a day) has been proposed, they fear the same pattern will be repeated.

“Hours weren’t cut but there was an increased expectation on productivity. A lot of benefits were taken away,” said Hilton Witbooi, general secretary of the Building and Allied Workers’ Union of South Africa (Bawusa). “We want to see all these issues covered in one agreement.”

But, said Witbooi, Bawusa was not included in discussions over a minimum wage. “The problem I have is that the federations are sitting there but are not covering the areas where we are. They are not speaking for us.”

He said he thought the current level (R2 780 a month, or R128 a day) is not enough. “It’s about time workers receive a decent salary.”

The idea is that the minimum wage of R3 500 a month, or R20 an hour, will be phased in over two years.

Unlike other employees, agricultural workers, it is proposed, will be paid 90% of this over two years. Domestic workers to be paid 75% of the R3 500 and the phase-in period will be three years.

Representing labour in the national minimum wage deliberation are the large federations – Cosatu, the Federation of Trade Unions of South Africa (Fedusa) and the National Council of Trade Unions (Nactu).

Cosatu’s last workers’ survey, in 2012, showed 20% of Cosatu-affiliated union members earned R2 500 a month and about 55% of their members earned more than R5 000 a month.

Nactu couldn’t provide statistics on what proportion of the workers its unions represented earned less than the mooted minimum.

Dennis George, the Fedusa general secretary, said the federation didn’t keep these statistics, but most of the federation’s members are part of bargaining councils and so their wages are higher than R3 500. “Those people [earning less] are basically voiceless,” said George. “You can see that from people who make pronouncements on their behalf.”

Some say they were not consulted at all and others believe that the input they provided was not adequately considered.

Myrtle Witbooi, the general secretary of the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers’ Union (Sadsawu), which represents 30 000 domestic workers and is a Cosatu affiliate, said the union had been asked for input but she believed that not much of it was taken into account.

She said the union had specifically requested that a national minimum wage should apply to its members. “We said to Cosatu, ‘We don’t want you to think for us,’ so we are shocked at the exclusion of some inputs from the agreement.

“The question is: Why are domestic workers so different? If we go to the shops, do we get charged differently because we are domestic workers? It is simply discrimination,” Witbooi said. “We have gone to several branches and the workers feel they deserve the same wage, or even much more.”

She said Sadsawu would appeal for more discussion on the matter, with demonstrations possibly on the cards.

Some officials are pleased with the progress in determining a national minimum wage but others would like to see much more put on the table.

Nosey Pieterse, the chief negotiator for the Rural, Agriculture and Allied Workers’ Union, led the strike in the table-grape growing area of De Doorns in 2012. “We were not directly involved in the negotiations [but] we have, however, submitted to the deputy president and we believe it has been considered.”

He believed the minimum should be higher. “When we went on strike in 2012, we had a very clear demand of R150 a day. But even if two farmworkers in the same household earn R150 a day, it is not sufficient to buy food that will provide the nutrients which are essential for a family.”

“So, when you look at a minimum wage, you need to look at it in that context.

“We actually need to talk about R250 a day, which would give you about R5 200 a month. So the suggestion of between R4 000 and R5 000 [as mooted by large organised labour], it would have been better.”

A spokesperson for the South African Cleaners, Security and Allied Workers’ Union, representing 16 000 members, said the minimum was too low. “We think it should have been at least R5 500. All the sectors must have provident funds on top of that and bonuses,” he said.

“We are writing to Nedlac [National Economic Development and Labour Council] and the department of labour as we speak and submitting responses to them now.”

The National Domestic Security, Agriculture and Allied Workers’ Union was also not represented in the negotiations but its general secretary, Emelon Khumalo, said he was pleased with the outcome so far because most Ndosawu members, being largely in the forestry and farming sectors, earned less than R3 500 a month.

“It is good, at least for a start. It has been difficult for us to get that [R3 500] and employers intimidate us, claiming that we would be retrenched if we go higher.”

If labour rejected the proposed R3 500 level, they would not be speaking for Ndosawu, he said: “We feel very strongly that, for us, it is a start.”

The threat of job losses would always be of concern, he said, but to have labour and the government behind a wage hike made Ndosawu feel more comfortable.

Business largely resigned to an increase

A proposed R3 500 for a national minimum wage has ruffled a few of labour’s feathers for being too low, but it has elicited a surprisingly muted response from business, considering many argued nothing more than R2 200 should be considered.

Gerhard Papenfus, the chief executive of the National Employers’ Association of South Africa, said his association was against a minimum wage, but now the debate was over and the decision to implement one had been taken. “In principle, a level of R3 500 is reasonably reasonable,” he said. “We still believe very vulnerable workers may lose their jobs. And it’s definitely not going to eradicate inequality,” adding that those who can get by with a smaller workforce will do so.

For those who can’t, the consumer will see the added cost in the price of goods, he said “If we can get confidence in the economy and confidence in our future, we will be able to deal with the rest.”

The African Farmers’ Association of South Africa welcomed the proposed minimum, but has called for assistance for smallholder farmers.

The association’s secretary general, Aggrey Mahanjana, said the wage was nowhere close to covering the basic cost of living, now estimated at more than R5 500 a month for a family of four, but the association “was not naive to the fact” that the majority of smallholder farmers could not afford the proposed minimum. He and the association have called on the government to provide smallholder farmers with a farmworker salary subsidy.

Business Unity South Africa released a cautious statement, saying it would consult its members and study the report, and consider its shared interests as a country in addressing poverty and inequality, without compromising employment given tough economic conditions. But it noted: “It is important to remember that the minimum wage initiative is one mechanism among several to reduce poverty and inequality, and that employment is the best mechanism address this.”

Some stats have defied predictions of job losses

Economic modelling by the treasury suggests that a national minimum wage of more than R3 000 a month will cause 715 000 job losses and see a 2.1% decline in gross domestic product.

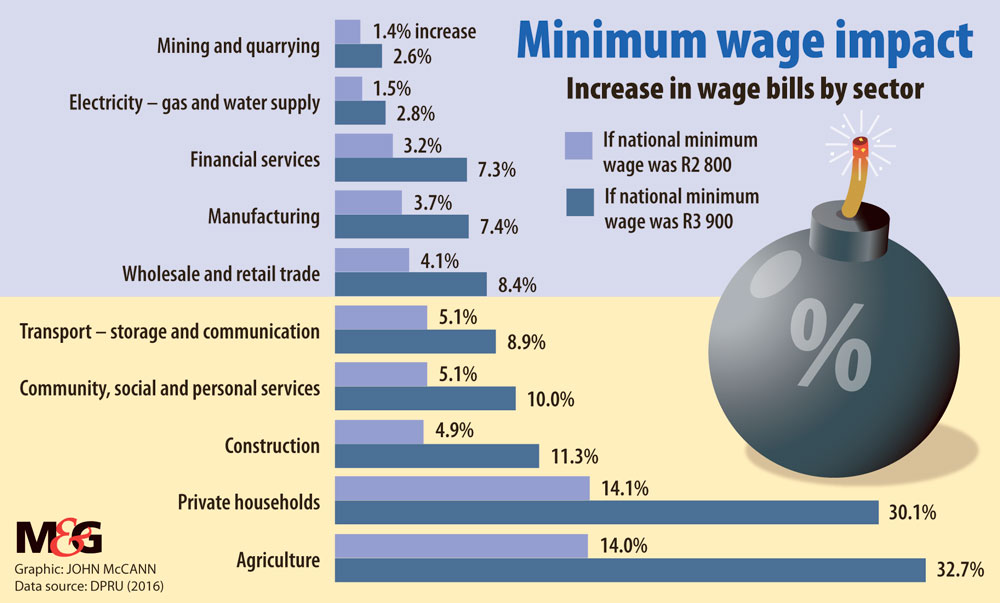

According to a 2016 paper, Setting Minimum Wages in South Africa, written by University of Cape Town academics Nicoli Nattrass, a professor in economics in the Centre for Social Science Research, and Jeremy Seekings, a professor of political studies and sociology, evidence suggests some sectors will be more affected by a hike in minimum wages than others.

They write that studies show the effect of minimum wages on employment is mostly modest when set at low levels. But job destruction occurs when minimums are raised dramatically, especially among less skilled workers in tradable sectors – those exposed to inter-national competition.

Those in “nontraded” sectors, notably domestic work and retail, are more adaptable to an increase.

Nattrass and Seeking refer to 2005 research showing that the introduction of a minimum wage in 2002 caused a drop in the hours worked by domestic workers but the increase in pay more than compensated for this and wage income increased.

“However, it is worth noting that there may be substantial noncompliance (reported levels of 39%) with regard to the payment of minimum wages to domestic workers, so it is likely that ineffective regulation also helped protect against job losses.”

In traded sectors, such as agriculture, it is different and the introduction of a minimum wage in 2002, researchers say, accounted for 200 000 subsequent job losses. Total earnings for these workers did not improve because higher wages were offset by reduced working hours. Noncompliance was also high in this sector at 53%, and probably cushioned job losses.

“According to national treasury, a national minimum wage of R1 886 would affect 45% of unskilled workers and 43% of farmworkers and 52% of domestic workers. Using a slightly different definition of a full-time worker, [Arden] Finn [a researcher at the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit] calculates that a wage of R3 000 would affect over 80% of agricultural and domestic workers,” Nattrass and Seekings write.

Nosey Pieterse, the chief negotiator for the Rural, Agriculture and Allied Workers Union, says the same argument about job losses was made when agricultural workers received a hike in 2013 but more than two years later employment has increased.

“They argue they will resort to mechanisation, like a sword hanging over our heads – but they are doing it, it is continuing, and we have been growing with mechanisation.”

According to Statistics South Africa data, employment in the agricultural sector has grown, along with the total labour force, despite a substantial hike in the minimum wage, which was thought would lead to job losses. In the third quarter of 2011, agricultural jobs tallied 624 000. In the third quarter of 2016, they had grown to 881 000. The number of domestic workers was one million, up from 880 000 in the third quarter of 2011.

On the whole, workers who will be affected by the agreement don’t believe that short-time is a real risk.

Hilton Witbooi, the general secretary of the Building and Allied Workers’ Union of South Africa, said an increase will instead place higher demands on productivity, which is not entirely unreasonable, but then the minimum must be set substantially higher than proposed to compensate for it.