Generally

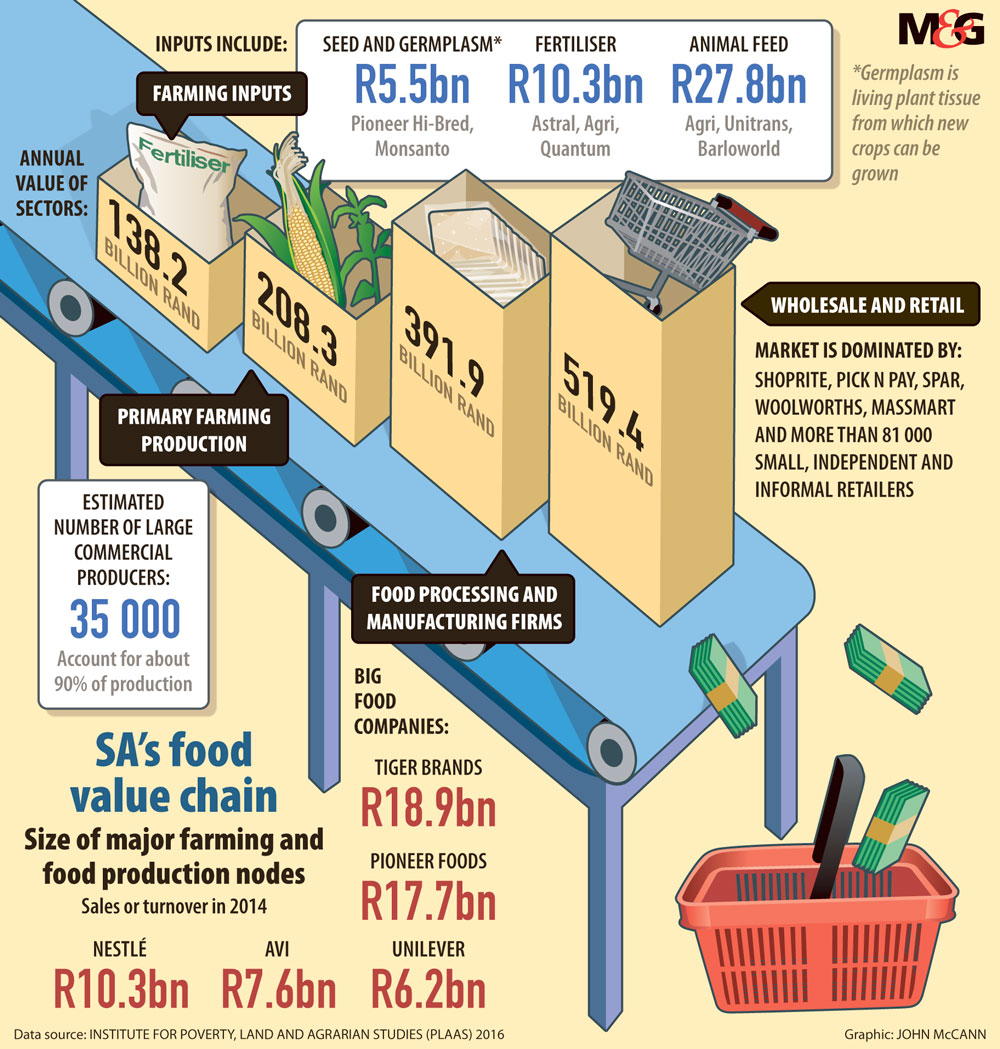

In South Africa’s food value chain, oligopolies exist in almost every link. From seed to store, just a handful of players control much of each market.

This is the last thing on the minds of most people when they fill their shopping baskets but it could be hitting them where it hurts most — in the wallet.

Concentration in a sector is presumed to lead to higher prices. The Competition Commission found the dominance of just a handful of players in the bread and cereals industry led to collusive behaviour, which pushed up the price of these goods.

In a 2016 report, the World Bank estimated that prices in South Africa for certain commodities were 20% to 40% higher as a result of cartels.

Counterarguments by Big Food are that a few dominant players in each link of the food value chain is the result of intense competition, and their economies of scale enable them to sources goods at the lowest possible price and pass it on to the consumer.

Intense regulation of the sector under apartheid saw some industry players flourish. Although the industry was deregulated post-1994, these players sustained their dominance and it was difficult for smaller competitors to enter the market.

Neva Makgetla, a senior economist at the economic research body Trade and Industrial Policy Studies, says Big Food is a highly concentrated sector and has not brought down real food prices, which have consistently risen at a rate greater than inflation over the past 20 years. “Basic economic theory suggests that the one has something to do with the other,” she said.

The Agricultural Business Chamber (Agbiz), whose members include major companies in the food value chain such as Monsanto and Tiger Brands, says, although there may be concentration in some parts of the value chain, essentially the South African agri-food system is an open and competitive market.

“The current food system without a doubt works for the greater good of society and results in lower food prices for consumers,” said John Purchase, the chief executive of Agbiz. “On a comparable basis, our food prices are of the lowest in the world and attest to the competitiveness of most of our value chains.”

Purchase said studies such as The Economist’s global food security index confirmed this. South Africa ranked 53 out of 117 countries in the affordability category of the index in 2016.

Purchase said concentration throughout the food industry is a result of businesses being forced to achieve extreme efficiency or be forced out.

“To be competitive in this global space, scale of economy, capital intensive technology and skills are critical success factors for all the businesses in the respective value chains, and this necessarily leads to concentration.”

This is also true for the global value chain, he said.

Generally, South African agribusinesses are small compared with some of the agribusiness giants that are increasingly investing in South Africa. “This is part of the globalisation process and [it] drives efficiencies that in the end benefit the consumer,” Purchase said.

Andries du Toit, a professor and director of the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (Plaas), said the effect of concentration on commodities should be assessed on a case-by-case basis. “My impression is that, when it comes to certain kinds of staples such as maize meal, chicken, et cetera, it does seem to be the case that our food system and producers are able to produce cost-effective products.

“But when it comes to fresh produce, small farmers and informal traders are often able to bring a product into poor settlements more cheaply,” Du Toit said.

Rising food prices hit the poor hardest. The annual food price barometer of the Pietermaritzburg Agency for Community Social Action, which follows the food basket inflation of low-income households, showed prices rose 15.1% from September 2015 to September 2016, admittedly aggravated by the effects of the drought.

General food price inflation, as reported by Statistics South Africa was 11.3% in September last year.

Tracey Ledger, the author of An Empty Plate, argues there are at least two important ways the current concentration of power in the sector is not working in South Africa’s interest.

Measures such as exclusive lease agreements have ensured the growth a few players in the food retail sector and has barred smaller players or forced them to pay higher rent — a matter the Competition Commission is investigating.

Then there is the way suppliers are treated, Ledger said. The share of the retail price of food that goes to farmers is declining and so increasingly the smaller farmers can’t survive. This is a key problem because agriculture is one way of creating growth in rural areas, Ledger said.

Some basic goods also have significant mark-ups from when they leave the farm gate until they reach the supermarket shelf, Ledger said.

For example, in 2015 one litre of fresh full-cream milk would cost R4.30 at the farm but retails for R12.19. Fresh chicken leaves the farm at R22/kg but retails 55% higher at R39.96 in the store. Fresh tomatoes are sold by the farmer for R5/kg but retail for R17.45.

The question of food quality is also important.

“There is an idea we are benefiting from the system because we all get access to cheap food. But we don’t,” said Ledger.

Studies show at least 80% of families cannot afford to buy adequately nutritional food and 25% of children suffer from chronic malnutrition, said Ledger. “Clearly, our food system doesn’t work for us.”

Between the agriculture business, manufacturers, retail chains and social grants, the system is fairly effective in providing the population with a diet that contains adequate calorie intake but is poor in terms of quality, Du Toit said. “It works to promote ultra-processed products, which are high in added sugars, fats and sodium. These are energy dense but nutrient poor. We have concurrently seen rapidly rising figures for diabetes and obesity as the consequence of a poor quality diet,” he said.

Ledger said: “The fact of the matter is that the role of a private company is to maximise profits for its shareholder … it is not the retailer’s job to ensure everyone has access to adequate nutrition.”

In deregulating the food industry post-apartheid, Ledger said the 1996 Marketing of Agricultural Products Act in effect removed the government’s power to intervene in agricultural markets to improve food security and nutrition. Still, section 27 of the Constitution makes clear access to basic nutrition every child’s right.

“Government does nothing to act on this … It is an astonishing omission,” Ledger said.

One consequence of fewer players in an industry is that jobs are squeezed out, Du Toit said. “In some ways, the presence of supermarkets has helped informal food service vendors in the former townships so one shouldn’t oversimplify issues. [But] it is clear our agricultural sectors are shedding jobs. Supermarkets are price makers and farmers are price takers. Small farmers are finding it difficult to survive in this difficult environment.”

Jobs in commercial agriculture dropped from 1.3-million in the 1980s to between 700 000 and 900 000 in 2016.

Du Toit said there are a number of good reasons to support smallholder farmers, not least because agriculture in rural areas acts as a social safety net for the poorest of the poor.

“In an economy with little prospect of employment in the urban areas to replace those lost on farms, highly concentrate food systems in a way manufacture poverty as it pushes people off the land and leaves them with no alternative. It creates conditions for serious political instability,” Du Toit warned.

Breaking up the food industry is as difficult as it is disruptive, said Makgetla. “It makes sense in some cases but we need to be aware of the cost.”

Purchase said it is necessary for smaller players, including smallholder and new entrant farmers, to access the commercial value chains. This will only be possible with a well-directed support programme, and preferably in partnership with the private sector, he said. Generally, there are support measures that can be introduced, “and, currently, there are already a number being implemented through various measures, and very successfully at that”.

Makgetla said current interventions were working but were not on a large enough scale. “People have been waiting 20 years for change, and the current rate is too slow.” The frustration gives rise to populism, she said.

Quick fixes might include interventions such as setting up shelves in supermarkets to be supplied with seasonal produce by local producers, with less stringent standards on quality and packaging, or providing space for food stalls outside of supermarkets.

But to be effective on a larger scale will require a holistic approach to address supply-side constraints and market access. Much will need to be done.

“We tend to give people money but the market institutions they need just don’t exist. We should be setting up institutions and support systems to a big enough scale that they make a difference and help small farmers, processors, retail outlets and food services,” she said.

Such institutions could come in the form of marketing co-ops, contracting schemes, incubators and state agencies, among others.

Directly addressing factors that drive high prices could be another consideration. “You would benchmark food prices to see what is driving up the prices, which might be input costs, logistics or monopoly power, and look at how to fix them,” Makgetla said.