Electricity pylons at Eskom's Koeberg nuclear power plant on January 9 2015 in Cape Town.

ANALYSIS

Remember the bad old days when the power supply was so tight that the mines were asked to halt production?

Now South Africa has gone from being an electricity-starved country to one that has 5 600 megawatts (MW) of excess during peak demand hours.

The change has been so extreme that Eskom is reportedly considering offering some industrial customers special pricing arrangements to stimulate demand, though it has been bruised by these deals before.

The power utility said last month the reversal was thanks to additional capacity being brought on line and improved performance because of maintenance and efficiency gains.

But the turnaround in the supply crisis has also coincided with two other major events, namely the steep tariff increases of recent years that Eskom has said it needs to bring new power stations on line and cover its costs, and a deep downturn in commodity prices and global economic growth. The decline in demand, in particular, has also called into question the need for 9 600MW of new nuclear energy.

Eskom spokesperson Khulu Phasiwe confirmed reports about the special pricing proposal but said it is currently limited to one company only, Silicon Smelters, and the proposal is limited to two years.

Eskom is waiting for a decision by the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) on a way forward, he said.

Moneyweb reported this week that Nersa would not grant the application without a regulatory framework in place, but “kept the door open” for the regulator to approve the application later this month, provided that the principles guiding a decision are properly set out.

Spokesperson Charles Hlebela said that the Silicon Smelters application was not supported by Nersa’s Electricity Subcommittee. The committee instead requested that a framework for dealing with such requests be developed to ensure that all such requests may be considered within defined parameters and on a transparent, consistent basis across all industries.

Some industry users have greeted the idea with caution, though others have welcomed it.

In the past when Eskom had excess supply, it followed a similar policy with the sale of cheap electricity to South32, formerly BHP Billiton, and its large aluminium smelters, Hillside and Bayside in Richards Bay, and Mozal in Mozambique. But the contracts hurt the utility financially and, during load-shedding, public anger was directed at the smelters because of their drain on power.

But the aluminium industry has been hit hard in recent years and illustrates the loss of major industrial electricity demand, which may be very difficult to restore. One of of South Africa’s only two primary aluminium smelters, Bayside, shut down in 2015.

The secondary aluminium industry has also seen dramatic declines. The number of secondary smelters has halved from 10 in 2009, according to Mark Krieg, the executive director of the Aluminium Federation of South Africa.

He did not have estimates for electricity use by the industry but the making of aluminium products declined from about 40 kilotons in 2008-2009 to 19kt by 2013, and it is fair to say that energy use halved as well, he said. These products included alloy billets for export and local foundries, deoxidants for the steel industry, aluminium powder for explosives and flocculants, and personal hygiene products.

The global shortage and resultant high price of aluminium scrap, which makes up for 75% of the secondary industry’s costs, has been the major challenge for the sector, said Krieg.

“Electricity price increases, of course, adds a further cost burden and, with reduced volumes, local secondary smelters are no longer globally competitive,” he said.

More broadly, foundry numbers in South Africa have been on the decline since 2000, according to John Davies, the chief executive of the South Africa Institute of Foundrymen.

About 70 foundries have closed since 2000, with about 170 still in operation. This has been for a number of different reasons, aside from electricity prices, which began to rise steeply in 2010, but the main one was a drop in orders, Davies said.

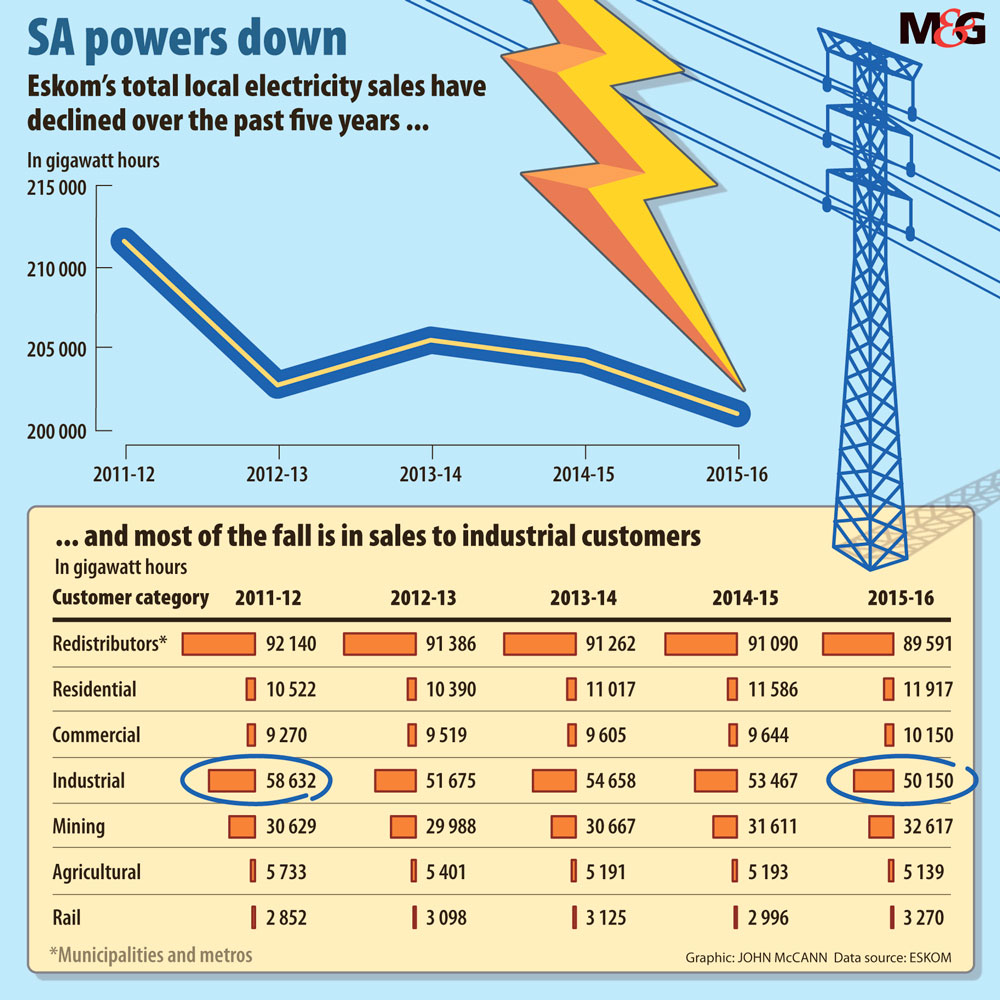

This is reflected by Eskom’s electricity sales, which has shrunk from 224 785 gigawatt hours in 2011-2012 to 214 487GWh in 2015-2016.

Davies and Krieg welcomed any measures to aid the industry.

With more increases in generating capacity on the horizon as Medupi brings an additional four units on line, and with Kusile still expected to be commissioned, “there will be even more electricity generated”, said Krieg. “Users of electricity are needed.”

But other large users were more cautious, notably the Energy Intensive Users Group (EIUG), whose members represent some of the largest energy consumers in the country, including South32.

“The subsidisation of industry is neither good for our competiveness or our fiscus,” its spokesperson, Shaun Nel, said. “Furthermore, special pricing arrangements might be seen as anticompetitive. We would rather the focus be on reviewing the electricity supply sector to make our electricity costs competitive.”

Eskom has since renegotiated the agreement for Mozal and only Hillside still appears to retain a special pricing arrangement. But the contract is subject to a legal impasse between South32 and Eskom, and it still remains a liability on the utility’s books. According to its 2016 interim results, Eskom recorded a R7-billion liability because of the contract.

The decline in demand and a capacity surplus questions the rational for the construction of a mega-fleet of nuclear power stations.

But, Phasiwe said, with Eskom’s aging power stations reaching their lifespan in the coming decade, Eskom has to plan to replace this base load capacity to avoid delays and cost overruns.

But the EUIG believes that “realistic cost assumptions and demand forecasts must be used in rational planning” to decide the future energy mix. Current indications are that nuclear will not be part of a lowest-cost energy mix, Nel said. “We need to learn the lessons from that period — South Africa needs to focus on investing in the least-cost options to provide electricity.”

Dave Mertens, a spokesperson for the High Energy Users Group, which represents several industrial users in the Nelson Mandela Bay Metro, said any attempts by Eskom to stimulate industrial demand must be done in line with the existing electricity regulation.

This means tariffs must “be cost-reflective, they cannot discriminate between customer categories and there cannot be subsidisation outside of that [regulatory] framework”, Mertens said.

The huge price increases that led to reduced consumption, particularly by mining and industry, has seen Eskom increase prices even more to combat the drop in sales, he said. This has contributed to a vicious cycle that needs to be broken.

In a bid to combat the impact of these prices on their business, the group has successfully challenged a recent tariff clawback that Nersa granted Eskom through a mechanism known as the regulatory clearing account .

Eskom and Nersa are both challenging the ruling, which was handed down in the high court late last year.

It is also not clear how easily South Africa can regain the industrial capacity it has lost in recent years. Reopening a business is notoriously difficult, said Krieg. Customers have been forced to find alternative suppliers, and may lack confidence in a company that has let them down.

Rapidly developing technology also means reopening a plant requires refurbishment and the upgrading of equipment, processes and systems to be competitive. But skilled workers will have gone elsewhere.

Neither South 32 nor Nersa responded to requests for comment.