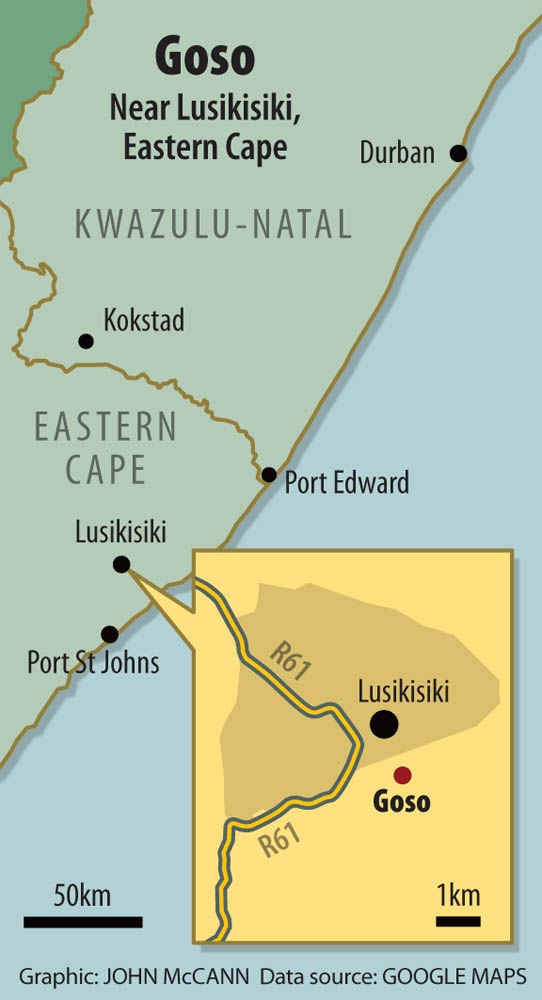

The Mayixhale home in Goso, on the outskirts of Lusikisiki, is only accessible by a rough gravel road. It lies above a small valley that serves as the family's garden and graveyard.

Goso, to use ANC secretary general Gwede Mantashe's description of nearby Port St Johns, is "untamed". This Eastern Cape village has schools and a clinic, but its gravel roads are hard to navigate.

In the Mayixhales's garden, there are sizable patches of sweet potatoes, taro (amadumbe) and a sprinkling of beans on a slope that runs towards a stream. The family still depends on the stream for water, as was the case when the Mail & Guardian first visited here about 10 years ago. Except for the installation of a prepaid electricity meter, the two-roomed house – painted a pale pink – has not changed since then.

There have been some new acquisitions, though. A stove and a flat-screen television fill up the living room-cum-kitchen area, near the door that opens out on to the yard. The Xhosa prayers beseeching God to wipe away all tears are still stuck to the living room walls.

Zandile Mayixhale, who now fills the big shoes left by the family's late matriarch, Bonani, says cooking on the stove depletes the prepaid electricity too quickly. That is why out in the earthen yard, diagonally opposite the two-roomed house, a corrugated-iron cooking structure still exists. Not far from the house, referred to as a "flat" in the Eastern Cape, a well-worn, legless cast-iron pot lies on ash-covered corrugated iron sheets, propped up by bricks.

Poor health

Bonani died from tuberculosis in 2010, before her house was electrified. She also missed experiencing the new pit toilet, a block brick cubicle that Zandile says will soon be full.

Coming, as we do, unannounced, with health worker Nomzwakazi Gogo again pointing out the way, Zandile is initially taken aback, but remembers speaking to the M&G on the eve of the last election, in 2009. She has a chocolate complexion and resembles her late mother – even though her features are obscured by an ochre-coloured face cream.

Her late mother, who now lies buried near the garden, had 10 children: seven daughters and three sons. Only half of her progeny (four daughters and one son) are still alive, dispersed across various cities and villages.

Zandile Mayixhale lives with her niece, Esihle, who is eligible to vote but did not register.

Zandile lives with her late sister Ntombenhle's daughter, Sinethemba. Sinethemba's schooling was interrupted when she fell pregnant with Babalo, who is few months old. Zandile's niece Esihle (19), who was orphaned when her mother died from an HIV-related illness, walks in with Zandile's two-year-old son, whom she was helping to get inoculated at a nearby clinic. Esihle's younger sister, Sisonke, is still in primary school. There are now nine people living in the house, under the care of Zandile and her sister Lizeka. Some are their siblings' children, others their own. Lizeka works for a retail store in Lusikisiki.

Zandile, meanwhile, receives a grant for three of her own children and a foster-care grant for the child of one of her sisters. She has not been able to find work since the nearby Magwa Tea Estate ran into financial problems last year and stopped paying its seasonal workers. "Besides the grant money, I can't say how else the government has helped me," she says. "The jobs that do come, from projects or whatever, you find that they have already hired the people by the time you hear about them."

RDP housing

She says the same thing applies to the RDP houses. "The councillor said they would choose who is eligible for housing, so I guess they will just choose who they want." Mayixhale has only recently registered for a house, but says she was told that only a select few in the ward will get housing because they are a "big" family.

Crammed into three beds – one in the lounge and two more in the bedroom – the family still manages to provide three meals a day. This is despite what she says are diminishing yields in the garden. "The mealies were fine, but it's not a lot anymore," she says, standing next to the desiccated post-harvest stalks.

Zanele and her fellow villagers cannot afford electricity, so they resort to other means

to keep body and soul together. (Photos: Delwyn Verasamy)

The diminutive Esihle, in jeans with her hair tightly plaited, should be in school uniform. She says the teachers bunk school after the term examinations; she saw a few "loitering" in town earlier in the day. Despite this, she aims to finish high school. The walk to Qikela High School takes between 40 minutes and an hour, depending on the route and the weather conditions.

Esihle says there used to be government-sponsored buses when she was at school in Flagstaff, but when this service was cut, she had to pay R260 a month for transport.

Some years after her mother died, Esihle started receiving a foster child grant, but the grant stopped when she turned 18.

Young mothers

Sinethemba, who quit school in grade 10 because of the pregnancy, does not receive a child income grant because she has no identity document. She was recently orphaned and her mother's funeral was held in the family graveyard.

Mayixhale says pregnancy also prevented her from finishing high school – the closest a family member who got to matric was Lizeka, who has dropped out with two subjects to finish. "In my case no one could look after my child for me, so I had to quit school."

In the sweltering heat, there is not much activity in the house. Zandile takes an afternoon nap while listening to a church service on the radio. Sinethemba tends to her baby, fanning her with a brochure.

Sinethemba and Esihle are of voting age. Esihle says she will not be voting because she has not registered, whereas Sinethemba hasn't made up her mind about politics.

When we last visited the Mayixhale household in 2009, Bonani, the late matriarch, said she would vote ANC because the councillor had said so.

Zandile, her daughter, was quoted as saying: "In 2004 we voted, but today we have no electricity. They promised us, but there is still no electricity. They are lying just to get our votes. I don't want to vote for just anyone now; I want to use my common sense."

Five years later, now with electricity but not much else, Mayixhale's position on voting, like her circumstances, does not seem to have moved on much.

"I may or may not go, depending on how I feel, because up to now, voting has not given me much in the form of tangible results. If I do bother, I may just vote for someone else."