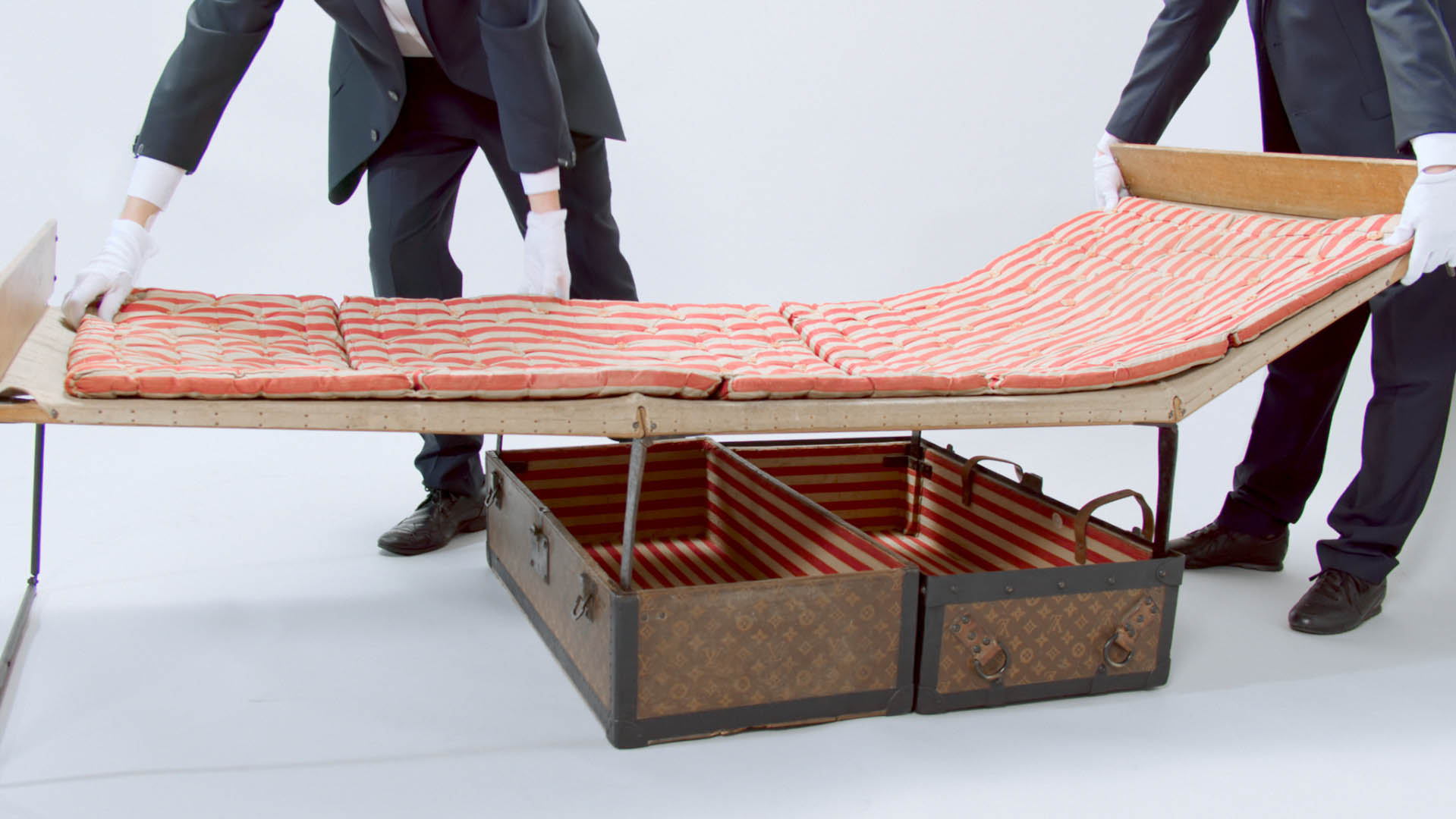

History unfolds: Stills from Bianca Baldi's video installation Zero Latitude that features the bed made from French explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza.

Colonialism, that vast European enterprise that involved shipbuilding, mapping, deal-making, mosquito swatting and guile, was backbreaking work. At least this is the impression one gets revisiting the biography of Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza, the Italian-French dandy whose biography animates Johannesburg-born artist Bianca Baldi’s video installation Zero Latitude.

One of four South African artists invited to show work on curator Juan Gaitan’s main group exhibition at the recent 8th Berlin Biennale, Baldi’s installation takes shape around a particular historical artefact: a custom-made portable explorer’s bed produced by Louis Vuitton, the moustached artisan-entrepreneur and box maker who lent his name to the monogrammed Parisian luggage goods brand.

A decade before the conclusion of the Berlin Conference (1884-85), which legalistically authorised the wholesale partitioning of political territory in sub-Saharan Africa, De Brazza, an Italian-born aristocrat with naval ambitions, was naturalised as a French citizen. In 1875, after graduating from a French naval academy, De Brazza embarked on a three-year trip to explore Gabon’s coastline and the Ogooué River. His luggage for the journey included a specially made Vuitton trunk that contained a collapsible bed frame, a hair mattress, two wool blankets and four sheets.

Although somewhat romanticised in French biographies, De Brazza was an instrumental agent of the European colonisation of Africa. According to the cultural historian Edward Berenson, De Brazza was a “godsend” to the beleaguered pro-colonial movement, which until then had faced fierce resistance among French citizens to expansion outside the borders of the country.

His mercenary adventure up the Ogooué River was purposeful and focused on discovering the source of the Congo River, a storied waterway that had long been a place of projective fantasy for sailors, explorers, artists and storytellers.

“The reason several centuries’ worth of visitors failed to explore the Congo’s source was that they couldn’t sail upstream,” writes journalist Adam Hochschild in King Leopold’s Ghost (1998). “Anyone who tried found that the river turned into a gorge, at the head of which were impassable rapids.” Although the Ogooué River did not connect with the Congo River, as De Brazza discovered in July 1877, he was able to find, map and even wage war on the banks of the upper Congo River. The narrative of this epic journey, undertaken with a group of nearly two dozen men, most of them Senegalese colonial troops, made De Brazza a celebrity in France.

With his dark eyes, Roman nose and slightly dishevelled aristocratic looks, he was a gift to the penny press. Felix Nadar, the well-known Parisian portraitist, made a series of studio photographs of De Brazza.

Baldi searched out these photographs in a Parisian archive as part of her research for Zero Latitude. Her walk-through installation, which shows two curators at Quai Branly Museum in Paris opening the Vuitton-made Explorator trunk, alludes to these portraits in a large wallpaper backdrop.

Baldi, who studied fine art in Cape Town and now lives in Frankfurt, is quick to concede that her walk-through installation is not a factual display with a “clear trajectory”. The installation does not include the original Explorator trunk, which she received permission to show, nor does it explicitly figure De Brazza. The setting, French Congo (now the Republic of the Congo), which she has never visited, is also held at arm’s length.

“There’s a tension between the real place and the imaginary one and, through making one connection, you come across others — such as the archetypical character of the explorer, De Brazza, his cultural and consumable baggage, as well as the histories of the Congo River,” Baldi recently told curator Clare Butcher.

The outcome is an imaginative conflation of history in which the image of the collapsible bed is presented as both a sculptural prototype, all gee-whizz in its strangeness, as well as a tangible relic of European imperial ambition. In certain respects, Baldi’s bricoleur’s approach to connecting seemingly disconnected historical facts is not that dissimilar in orientation from photographer Santu Mofokeng.

A garrulous conversationalist recently suffering from a bout of voicelessness caused by clotting in his blood, Mofokeng also had work on the Berlin Biennale. Although younger artists Kemang wa Lehulere and artist collective Centre for Historical Reenactments might have occupied a more vanguard position with their presentations, Mofokeng was undoubtedly the most celebrated out of the quartet of South Africans showing work, certainly in Germany. Last year he was invited to show work with Chinese provocateur Ai Weiwei, French film director Romuald Karmakar and Indian photographer Dayanita Singh in the German Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale.

He presented new landscape studies of ancestral graves endangered by mining in Mpumalanga alongside portraits of black families made between 1890 and 1950, which he unearthed during extensive field trips across the country in the early 1990s.

Known as The Black Photo Album/ Look at Me: 1890–1950, the latter project was first exhibited as a slide-show at the 1997 Johannesburg Biennale. Last year Gerhard Steidl, the Göttingen-based photobook publisher widely known for his singular devotion to excellence in book production, released a stunning print version of the project, which is grounded in visual anthropology but leavened by the artist’s ongoing quest to photograph the impossible — ephemeral things such as faith, spirituality and the lingering shadow of ancestors.

Anthropology, the scientific study of us — our kind rather than our humanity — is a useful tool for artists of all stripes. Speaking on a panel at the 2012 Frankfurt Book Fair, David van Reybrouck, a Flemish-speaking Belgian journalist and playwright, remarked how most colonial and post-independent histories of Africa have been written from an elitist perspective.

Protagonists, whether coloniser or oppressed, are typically always privileged.

“Africa is more than its elites,” insisted Van Reybrouck, whose award-winning book Congo: A History (2010) draws on testimonies of 500 mostly ordinary people.

During his talk Van Reybrouck stated that there is a need to widen the scope of history writing. The challenge for anyone interested in probing the Congo Basin’s tragic story — although the logic can be applied more widely — is to eschew “glorious history” and write an “anthropological history”. This is exactly what Baldi and Mofokeng are doing.