Jean Kufil Lukila

A group of 25 Nigerians ended their two-week hunger strike at the Lindela Repatriation Centre after a brutal attack on them allegedly by security guards who were apparently trying to force them to eat. The guards work for Bosasa Operations, the company charged with running the centre.

READ MORE ON LINDELA

Five members of the group claimed that 10 guards shot at them with rubber bullets and beat them with batons.

As part of an investigation into Lindela, the Mail & Guardian went undercover and visited the high- security facility in Krugersdorp on the West Rand last week where the men told us they ended their hunger strike after the attack.

The men showed us wounds they claim were sustained in the alleged attack that took place two weeks before our visit. We met in the facility’s visitors’ room.

“I was not being treated for injuries despite that the centre has a clinic inside,” said one of the men, who did not want to be identified out of fear for retribution.

The man was in the company of four other detainees who constantly interrupted him as he spoke, anxious to voice how they were allegedly brutalised by the security guards. They repeatedly claimed they were beaten with batons and shot at with rubber bullets at close range. The faces of the four were still swollen.

“They shot us at close range with rubber bullets,” said one of the men. “The security guards wanted to stop the hunger strike and used the rubber bullets to shoot at us to make us eat.”

Let the world know

Taiwo Olagunju, said: “Brother, I hear that you are a journalist. Please, we would like the whole world to know how we are suffering inside here. Some of our fellow detainees were shot in the head. They are inside there and still have open wounds in their heads.”

Olagunju didn’t have visible wounds but complained of pain where he had been hit with a baton.

The alleged attack comes in the wake of a strongly worded judgment in the high court in Johannesburg and associated recommendations by the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) that would give it access to and oversight of Lindela.

In August the Johannesburg high court ruled that the detention of a number of inmates had been illegal.

Illegal immigrants may be held for no more than four months, but that rule is regularly flouted at Lindela.

Halfway house

Lindela was founded in 1996 as a halfway house before illegal immigrants get repatriated to their home countries. It has been embroiled in controversy since its inception. The centre was initially owned by a consortium of ANC Women’s League leaders. In 2000 the politically connected Bosasa took over the running of Lindela on behalf of the department of home affairs. The contract is worth R90-million, although exact details of the commercial arrangement have long been kept secret.

The five detainees told the M&G that they went on a hunger strike to draw attention to the conditions in the facility. They allege that most of the detainees at Lindela, especially those from Nigeria, have been illegally kept there for more than 120 days. Their other complaints include no access to legal representation, overcrowding, bad food and poor treatment by the centre’s staff.

Jean Kufil Lukila (44) was arrested in 2011. His asylum-seeker permit had expired and he was held for 162 days at Lindela. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

Their version of events was not corroborated by other witnesses, but a number of reports, court cases, investigations and independent verification by credible human rights organisations and lawyers, over more than a decade, paint a picture of abuse, torture and the trampling of detainees’ rights.

Bosasa spokesperson Papa Leshabane said he would not respond to allegations of security guards shooting and beating detainees until he had viewed CCTV footage of the alleged incident. He referred questions about the hunger strike to the department of home affairs. Despite repeated requests for comment the department of home affairs did not respond.

During our visit a Malawian detainee announced that he and many of his compatriots had also started a hunger strike.

Detainee numbers

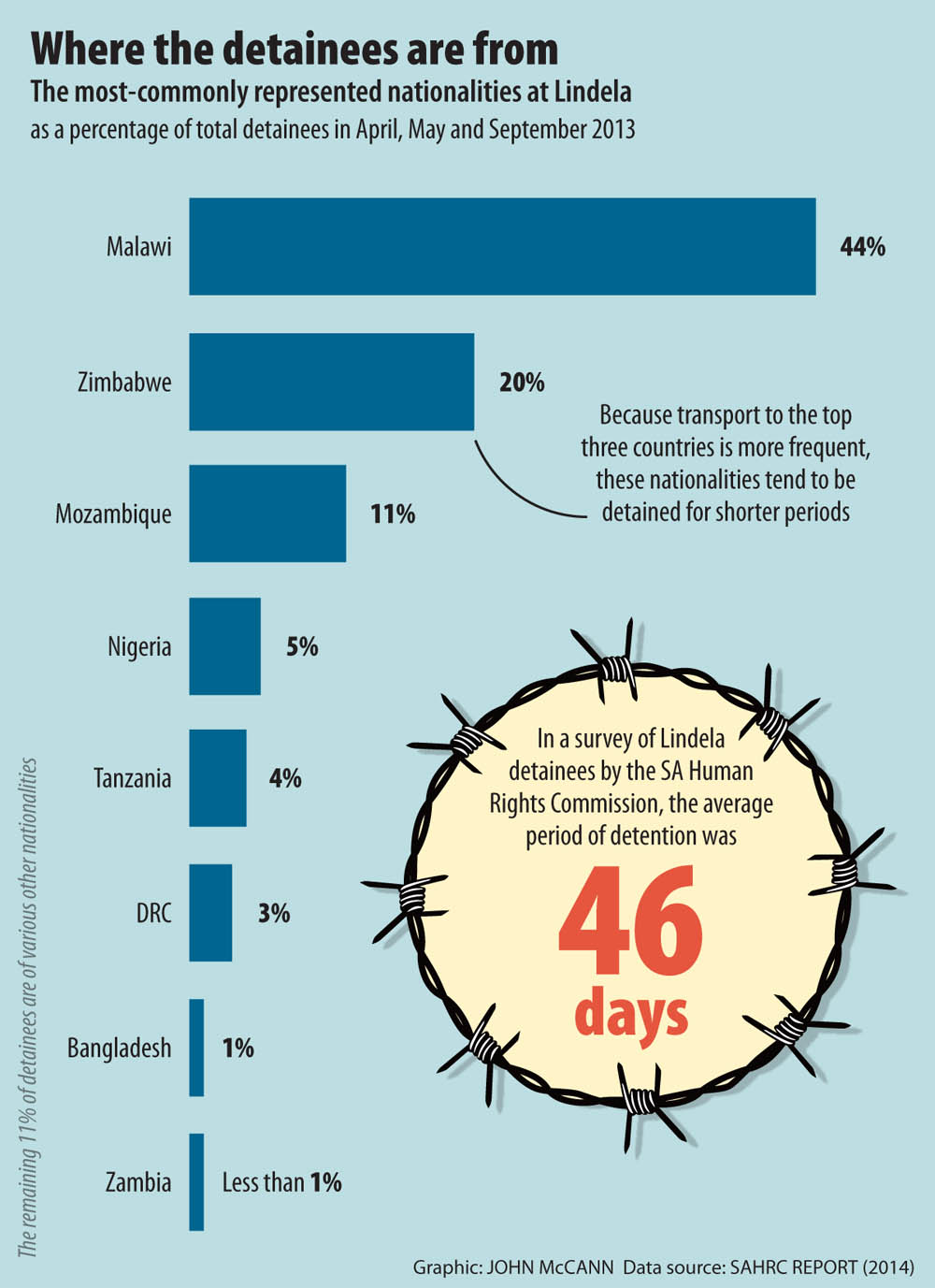

Lindela can accommodate up to 4 000 detainees. At the moment there is an unconfirmed number of between 2 000 and 3 000 people, many of them Malawians.

Another Malawian, Hope Ngoma (31), corroborated the claim, saying that about 1 400 Malawian detainees embarked on the hunger strike on Wednesday, October 1.

“I don’t know how long it will take but they are adamant to continue with it until their demands [to be] deported are met,” he said.

Detainees are served two meals a day – breakfast at 8am and supper anytime between 2pm and 6pm.

A Malawian woman, who had come to visit her husband, said she wanted to buy a plane ticket for him but was told he was on the next list of those who would be deported “soon”.

“Life can’t be good with your partner in jail. I have a little daughter who is going to school.

“It is difficult to make ends meet with only my salary,” she said, just before the M&G was told our visiting time was up.

Allegations of violence

A number of former detainees made allegations of violence against Lindela inmates.

Blaise Lotele (39), who was held at the centre in 2012 after his asylum-seeker permit had expired, said the abuse of detainees was not new.

Lotele is a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). He recalled that a fellow Congolese died at the centre after he fell sick, coughing terribly and vomiting blood.

Blaise Lotele (39), who was detained in 2012 after his permit had expired, says the abuse of detainees is nothing new. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

He said the man was not given proper medical attention.

“I was beaten once before I told them [the security officers] that I am a pastor,” Lotele said. “Every time when they come to beat up detainees, they would first ask me to get out.

“There was a big man who beat me seriously.”

Documents

A Malawian, who lives in Roodepoort, said he was detained at the facility in 2003 for 145 days, after he was arrested for not having his documents in order.

“Back then things were worse,” said the man, who did not want to be identified. “It is not nice inside there. I spent more than three months there. On the day I was deported I was hit on the cheek by a big security guard who told me never to come back again.”

He alleged the security guards would attack the detainees whenever they complained about the poor conditions in Lindela.

“The guards would fire rubber bullets at the detainees in the detention [centre],” he said.

Another former Lindela detainee, Jean Kufil Lukila (44) from the DRC, was arrested on October 17 2011. His asylum-seeker permit had expired and he was held for 162 days in Lindela.

“There were too many people in one room and people fell sick,” he told the M&G at the Johannesburg office of the African Diaspora Forum, an organisation representing the rights of migrants.

“When they go to the clinic they give them only Panado tablets.”

No ‘proper medication’

He also recalled the incident when “a Congolese died because he vomited blood and was not given the proper medication”.

It seems there is a change of heart in the home affairs department. It had initially said it wanted to appeal against the high court judgment.

But, said the provincial manager at the SAHRC, advocate Chantal Kisoon: “I think there is willingness on the part of the new minister to comply with the judgment.”

Malusi Gigaba took over as home affairs minister from Naledi Pandor in May.

Kisoon said the commission would visit Lindela next week and release a statement on the situation at the centre.

Legal recourse denied

Legal Resource Centre attorney Naseem Fakir, who has been working on cases involving Lindela detainees since 2007, said people were often denied the right to seek legal recourse.

Fakir recalled a case involving 40 detainees who were released before the case could be heard in the Johannesburg high court. The home affairs department could not account for about eight of them.

“In 2012 this office alone had 50 people who were unlawfully detained at Lindela [and] released by way of court application,” she said. “That was before the next application to release the 40 foreigners.”

The application for the 40 was made in October 2012.

Last month the SAHRC completed a report on its two-year investigation into healthcare at Lindela. It found that there was a “lack of measures to ensure continuity of treatment with respect to chronic medication, particularly with regard to TB and HIV treatment, among other findings”.

The report recommended that the home affairs department “should provide the commission with a comprehensive report outlining the challenges it has identified and steps it will take to remedy such barriers to the realisation of the right to healthcare”, among other things.

‘Not enough proof’

Fakir said: “In 1996 there was a court order that the department should do a monitoring of Lindela, but ironically we complained about the same thing in 2012.”

She said the department’s lawyers told the court “that we don’t have enough proof that people are held in Lindela for longer time”.

“It is difficult for the detainees at the centre … They are not told that a warrant from the magistrate has to be obtained for their detention.”

Rapula Moatshe is the Mail & Guardian‘s Eugene Saldanha fellow for social justice reporting.

South Africa stumbling on refugees’ human rights

South Africa is slipping on certain human rights issues, which is sad, given the country’s rich legacy, Amnesty International secretary general Salil Shetty told the M&G this week.

Speaking from Amnesty’s new regional offices in Johannesburg, Shetty said: “South Africa, given where it comes from, had a very progressive refugee protection mechanism and policies. What we’re seeing in recent times is an erosion of that.”

Shetty decried the dishonouring of the non-refoulement principle in particular, which says a country should not send a person back to their country of origin if they are at risk of harm. “The situation in Somalia in terms of human rights – we know is not the best for the South African government to send Somalis back. ”

Although it was understandable that governments needed to protect their borders, there were “rules of the game”, said Shetty, referring to international refugee law and United Nations protocols. “I’m told in the case of South Africa right now the rejection rate for asylum seekers is above 90%. If you’re accepting less than 10% of the people who are applying, it comes into question whether there are due processes being followed.”

Shetty was careful to emphasise that this was a global problem. “I’m saying this to you because normally when we are critical of governments in the developing world, they always say you know this is a Western agenda, so Amnesty is clear that this is actually a generic problem.”

South Africa has made important progress, Shetty emphasised, but said these were issues that all countries in the developed and developing world had to improve upon.

Ultimately the solution is for regional powers to be more influential – preventing situations that result in illegal migrants flooding their borders in the first place.

“We need to make sure in the first instance that the countries where they are coming from are supported, because we don’t want them to have to leave their countries. What has South Africa done about the Zimbabwe situation? The challenge coming from South Africa has been muted … it’s about addressing the causes rather than dealing with the consequences.” – Verashni Pillay

The cost of detaining immigrants

The costs for deporting illegal immigrants has increased from R165 894 000 in 2010 to R199 850 936 last year, according to a written reply by Home Affairs Minister Malusi Gigaba to a parliamentary question by the Democratic Alliance in July.

Dr Roni Amit of Wits University’s African Centre for Migration and Society said it was difficult to specify the exact number of illegal immigrants in the country, but estimated that there are between 1.6-million and two million documented and undocumented immigrants, and from that number it is not known how many are undocumented.

She does not know how many migrants are arrested daily, but according to the detainees the M&G spoke to at Lindela Repatriation Centre, at least 150 foreigners are transported to the centre every day.

Research authored by Darshan Vigneswaran and Marguerite Duponchel into immigration policing in 2009 suggested the number of deportations was 312 733 between 2007 and 2008 — six times more than those between 1989 and 1990.

The amount paid by home affairs to Bosasa Operations, the contractor that operates Lindela, is R65 a detainee a day, according to the research.

The 2009 research found that the Gauteng police spent more than R362.5-million a year on detecting, detaining and transferring illegal migrants to Lindela.

The South African Human Rights Commission recommended that home affairs should put a monitoring mechanism in place at the centre.

According to Gigaba, no one is currently being held at Lindela without a warrant.

But Amit said: “This has been a consistent problem at Lindela noted in numerous reports and court cases.” — Rapula Moatshe

In a previous version of this article it was stated that the number of illegal immigrants in the country is estimated to be between 1.6-million to two million, when in fact it is estimated that there are between 1.6-million and two million documented and undocumented immigrants in the country, and from that number it is unknown how many are undocumented.

The article also stated that research into immigration policing in 2009 was authored by Roni Amit, when in fact it was authored by Darshan Vigneswaran and Marguerite Duponchel. We apologise for the errors.