The AU's 25th summit in Johannesburg was expected to address xenophobia and other matters seen to be threatening peace and stability on the continent.

NEWS ANALYSIS

African solutions should be found for African problems – but when it comes to money, this notion is compromised. More than half a century after it was formed as the Organisation of African Unity, the African Union is still struggling to be financially self-sufficient.

The AU set a $292.8?million budget for last year. This works out at slightly more than R3-billion at today’s exchange rate, and is far less than this year’s R52.6-billion budget for the City of Johannesburg, where the AU leaders’ summit is taking place this weekend.

The organisation has approved $426?million (more than R5-billion) for 2014, but relies heavily on donors. Only 33% of the budget is expected to be raised from member states and the rest is to be sourced from international and development partners.

At the top of the list of AU’s development partners are countries such as Canada, Sweden, Germany, the Netherlands, the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, China and Turkey, as well as organisations such as the World Bank and European Union.

Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, shortly after taking up the position of AU Commission chairperson, raised concerns about the organisation’s heavy dependence on funding from the West. This posed the risk of those countries dictating the AU’s activities, she said at the time.

But not all the money pledged is paid to the AU. By the end of last year, the AU had received only 54% ($154?million) of the money it had budgeted for.

Financial problems

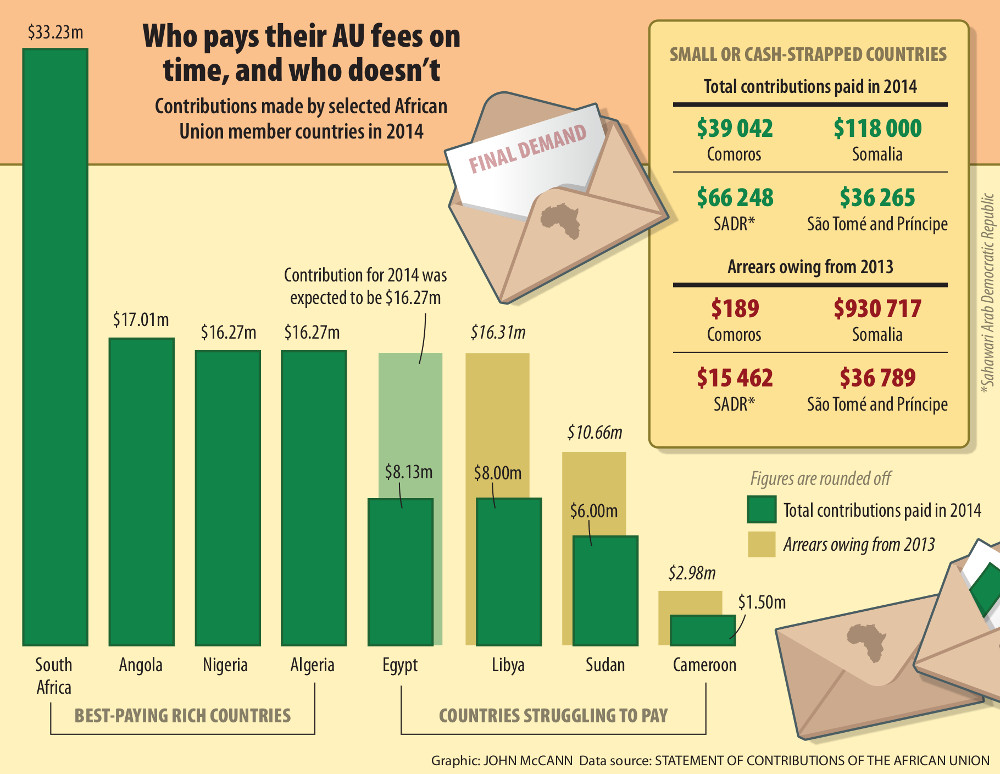

The AU’s financial problems are compounded by the fact that some member states fail to pay their dues. The organisation collected $84.6?million from member states last year (much less than the anticipated $138.5?million), a 67% rate of collection. Its international partners paid $67.1?million instead of the expected $287.7?million – a mere 23% of the pledges made.

South Africa is one of the biggest contributors among the AU’s members, but more is expected. The AU summit in January decided that six countries (South Africa, Nigeria, Algeria, Angola, Egypt and Libya) should increase their contributions because they are considered to be wealthier than their other African counterparts. They are expected to cover 60% of the AU budget, starting from next year.

A meeting of the AU’s subcommittee on audit matters, held in Addis Ababa two weeks ago, heard that the AU could not execute some of its planned programmes because of the late receipt of funds or lack of funds from donors.

The meeting concluded that “only programmes that have secured funds from partners should be included in the union’s budget” and “the commission should ensure compliance with the signed contribution agreements entered with the partners”.

The AU’s budget execution report for January to December 2014, tabled in March this year, stated that, “despite high approved budgets, the funds released and the contracts/terms of engagement signed by the development partners were too insignificant. This low commitment from the partners left the AU with a huge budget deficit.”

The report added that other ways of funding have to be established in order to increase the funds available to carry out the AU’s activities.

Member contributions

Only 67% of member states’ contributions were received, “which affects implementation of the activities financed by the member states. There are also outstanding balances amounting to $39.5?million brought forward from the previous year’s assessed contribution,” the report stated.

It proposed forming a committee to visit the member states that owe the AU money and convince them to pay their contributions and arrears.

“There is a need to revise the scale of assessment to ensure that the contribution to the AU budget is spread among more than five member states in order to reduce the burden of the current five member states that contribute 75% of the total AU assessed contribution.”

The AU is now hoping to have a budget of more than R6-billion ($523.8?million) for 2016 and said its main development partners “will remain key to the financing of programmes and projects of the union. In 2016, partners are expected to contribute $362-million, representing 69% of the total budget, mainly to fund programmes as per signed agreements,” according to the AU’s 2016 draft consolidated budget.

Referring to increasing what well-off countries need to contribute, the draft budget stated that, with the demonstrated political will to finance the affairs of the union from treasuries and other sources, member states would meet the spending requirements.

“Although its implementation will stagger over three to five years to allow for countries to adapt to the new formula, it will however be a major departure from being predominantly dependent on partners for programme funding towards self-sustenance, self-pride and belief that African problems can be solved with Africans and accountable to Africans,” it stated.

Levy proposal

The AU has proposed possible levies to increase the organisation’s finances, but the most attractive one – an oil levy – was rejected by oil-producing countries.

Levies currently on the table are a $2 hospitality levy on hotel stays, a $10 airfare levy on each international flight entering or leaving Africa and a $0.005 an SMS levy, though counties that depend on tourism have objected to hotel and airfare levies.

This week, AU Commission secretary general Jean Mfasoni told the media that, “in the spirit of African solutions for African problems, African states should contribute more to finance the AU”.

Mbasoni said the AU would allow member states to determine for themselves what sources they will use to pay their dues.

But, he said, this week’s summit might not make a final decision on alternative sources of funding for the AU, though it should come closer to reaching a solution.

Meanwhile, International Relations Minister Maite Nkoana-Mashabane said earlier this week the AU could fund all its programmes if it were not losing a huge amount of money because of the illicit outflow of capital from the continent.A

SA issues top summit agenda

When African leaders meet this weekend for the African Union summit in Johannesburg, it will be an opportunity for South Africa to show it hasn’t turned its back on the rest of the continent.

In an unprecedented move, xenophobia and migration were placed as one of the first items on the agenda to be discussed behind closed doors by heads of state – before the biannual summit’s opening speeches. This follows the outcry over April’s violent attacks in South Africa.

The summit in Sandton on June 14 and 15, which has been preceded by preliminary planning meetings focusing on crisis hot spots, will also be an opportunity for the AU to try to raise funds for the running costs of its commission in Addis Ababa.

Even if members of the South African business community put their hands deep in their pockets to help the AU, it might not be enough to ensure Pretoria retrieves its image of championing African unity – as was the case during the Mbeki presidency and, for a time, before the outbreaks of xenophobia.

On Monday, the minister of international relations and co-operation, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, dismissed suggestions of a boycott by some heads of state due to the perception that South Africa is hostile to other Africans.

Heads of state including Malawian President Peter Mutharika and Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe condemned the xenophobic violence at the time. Nigeria temporarily recalled its high commissioner from Pretoria following the attacks.

“South Africa will have to discuss its position on xenophobia, even if people generally agree with the way the government is handling it,” a high-ranking AU official told the Mail & Guardian in Addis Ababa.

At the end of April, the AU’s 15-member peace and security council held a special session on xenophobia in Addis Ababa, when South Africa’s ambassador to the AU was asked to explain the country’s position.

South Africa’s membership of this council – an increasingly important instrument to act speedily on security issues in Africa, similar to the role of the United Nations Security Council – expires at the year’s end; whether or not it will be re-elected by its neighbours in the Southern African Development Community to serve another term will be a test for the country’s credibility in the AU.

Next year, the first four-year term of AU Commission chairperson Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma ends. If she runs again, she will be up against stiff competition, mainly from those who believe she did little to build the institution’s image and did not communicate effectively about what she has been doing in the AU.

Observers say that, for the AU summit to be a success, it’s important for leaders to be seen to take strong action on the issues that threaten peace and stability in Africa.

Currently, attempts by leaders in Africa to extend their terms of office to a third term is causing civil unrest and political uncertainty in countries such as Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Burundi’s crisis – where the government and civil society activists have been involved in a violent standoff and thousands of people have fled the country – will be on the agenda of the peace and security council summit on June 13. So far, the AU and regional leaders have not managed to discourage Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza from standing for a third term.

President Jacob Zuma is involved in trying to solve the Burundi crisis. He is also a member of a newly created high-level panel to try to bring peace to war-torn South Sudan. In addition, South Africa is a member of the international contact group for Libya that is meeting on Saturday on the AU summit’s sidelines.

Initiatives such as the African Capacity for Immediate Response to Crises (Acirc) are also expected to be discussed at the summit. Some members want to see it scrapped and incorporated into the African Standby Force, which already has a rapid response capability, even though it has not yet been operationalised.

Zuma initiated Acirc in 2013 after France was called in to intervene in Mali, causing embarrassment among African leaders about the absence of an African intervention force that could react in crises. – Liesl Louw-Vaudran