Seven years after official data first revealed that about half of undergraduate students drop out of university without completing their degrees, new figures show no improvement in this poor academic performance.

Educationists and students said inadequate assistance, poor academic support and family pressure contributed to high dropout rates.

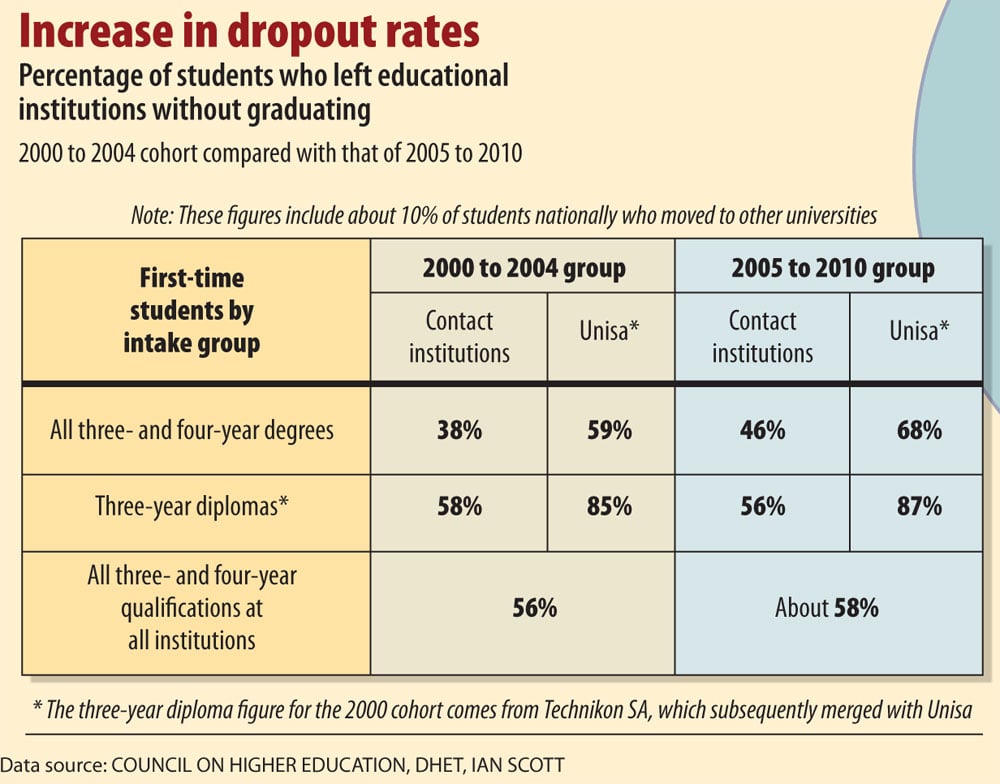

Some 46% of all students who started studying three- and four-year degrees in 2005 at South Africa's 22 universities, excluding Unisa, had dropped out by 2010, according to data newly published by the Council on Higher Education, a statutory body that advises the education minister (see graphic above).

The council's figures omit Unisa because distance-education programmes generally take far longer to complete. But the national picture worsens dramatically if you include it. Official figures for the same six-year period show that 68% of Unisa students left without graduating, Ian Scott, the director of the University of Cape Town's academic development programme, told the Mail & Guardian.

Unisa has more than 300 000 students, about a third of the country's entire university enrolment.

The latest numbers are remarkably close to the figures the M&G first reported seven years ago, based on the students who entered tertiary study in 2000 ("Shock varsity dropout stats", September 22 2006).

Students at the University of the Witwatersrand said these dropout rates did not surprise them.

No one "babies" you, said first-year student Chantal Motsuenyane. "It's so different to school. If you do badly at something, no one tells you why. There are student advisers, an internal network and tutorial sessions, but it still feels like you've been thrown in the deep end. I feel like even if I went to a lecturer, I wouldn't get the help I need."

Ntobeko Khumalo spoke of family pressure to pursue qualifications that students might not choose themselves.

"You get a guy who comes from the rural areas and he is probably the first person in his family to go to university and their hopes are all on him," she said. "His family doesn't want him to study a BA, they want him to be an engineer or a doctor. But sometimes he isn't interested in those things, so he loses commitment."

Ahmed Essop, the council's chief executive, said all universities had support programmes for students who were not adequately prepared for higher education.

But "the full impact of these programmes is limited because [state] funding is provided for a maximum of 15% of an entering cohort and because the programmes are an add-on. [They] have not resulted in a fundamental reform of the curriculum structure, which may be necessary, given the extent of the problem."

The nongovernmental organisation South African Education and Environment Project helps young people to prepare for university and supports university students. Its social worker, Kayin Scholtz, said universities needed to make "real access to help a priority".

"None of the students I've worked with who have dropped out of university … accessed any resources like emotional counselling," he said.

"They don't know what services there are. Whether or not this is given to them in orientation [week], it's definitely not given to them in a way they can understand it … Multilingual support is also critical, as are mentors."