On the Greek island of Rhodes, a 30m bronze statue of the islanders’ patron god, Helios, famously known as the Colossus, watched over the harbour for more than 50 years, until it was felled by an earthquake in 226BCE. Ptolemy III offered to rebuild it, but the Oracle of Delphi said the people had offended Helios, and the bronze fragments remained where they lay for 800 years before they were hauled away.

No one knows where the Colossus stood or what it even looked like, which can be said of the majority of Greek bronzes from the period marked by the end of Alexander’s reign in 323BCE to the beginning of the Roman Empire. The sculptor of the Colossus, Chares of Lindos, was a student of Lysippos, Alexander’s court sculptor, and was regarded as the finest in the medium, but, of his 1?500 works, none has survived.

Today, less than 200 large-scale bronzes of the era remain, and 47 of them are on display in Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World, at the Getty Centre in Los Angeles. With loans from 34 museums in 12 countries, this once-in-a-lifetime exhibition includes many national treasures never before assembled in one place. The show stops in three cities only: it went to Florence in March, and travels to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC this December.

“It’s two terms that are meant to distil what Hellenistic sculpture is about. Ruler culture emerges as a genre in this period,” is how the Getty curator of antiquities, Jens Daehner, explains the show’s title. Co-curator Kenneth Lapatin adds: “Pathos in Greek means a kind of lived experience, as opposed to the ideal figures.”

A new political reality framed by Alexander

That last remark is part of what separates Hellenistic bronzes from their predecessors. Where earlier archaic and classical subjects were mainly mythical figures and demigods presented in idealised form, the Getty show features everyday people, noblemen, artisans and athletes, reflecting a new political reality framed by Alexander and his successors.

Most finds are in secondary and tertiary locations, separate from their original bases describing the work. As such, the figures represented are mostly anonymous civic leaders, wealthy patrons, fellow citizens and the deceased.

Among the show’s highlights is the Terme Boxer, a rare and pristinely preserved large bronze excavated in 1885 on Quirinal Hill in Rome. Although he is missing his stone-and-glass inlaid eyes, teeth and the reddish hues meant to signify blood on his belted knuckles and open wounds, he is the very embodiment of the show’s title. His powerful though enervated frame and pain-wrenched expression exquisitely convey physical and mental exhaustion after a fight.

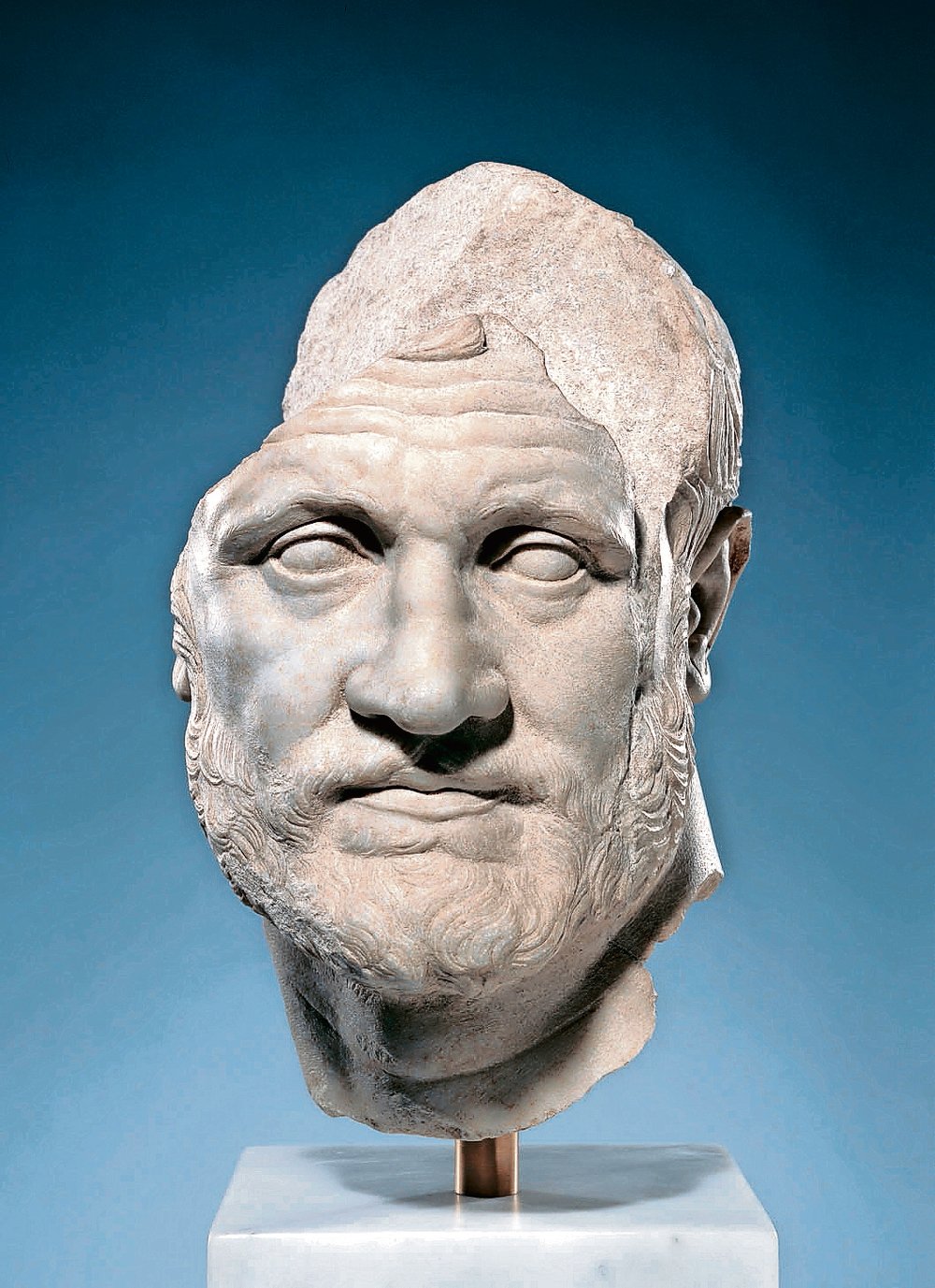

Portrait of a Bearded Man

“It rewards the remote view with its sheer power and its intention and composition, but it also rewards a very close-up view where you can see details,” says Daehner about the broken nose and flesh wounds, but more importantly the softly textured hair and beard. “It’s a kind of realism that is unusual.”

Statues from this period are mimetic, meant to be so realistic they could actually conjure the aura of the person represented. Bronze was ideal for detailed articulation because original models were modelled in wax, affording artists greater malleability when sculpting delicate features. Composed of hollow casts, statues were lighter than marble, and the tensile strength of bronze afforded a greater range of physical expression.

A lifelike illusion

Because of corrosion over time, today most of the bronzes are black. But they originally bore a tone similar to that of Mediterranean skin, sometimes with silver fingernails, copper lips, ivory teeth, fine copper eyelashes, and often augmented with colour to create a lifelike illusion.

Although the Hellenistic style is usually described as naturalist, it is a label that makes Daehner bristle. “Realism is a more practicable term. A face with wrinkles, you can call it naturalist, but the person you’re portraying doesn’t necessarily look like that,” he says, listing the artist’s priorities at the time. “What the portrait does [is] sending a message, showing a person at a particular age, the social status of that person – the statue needs to convey that because that is more important than if they can capture a resemblance.”

Because many of the statues only survive as marble copies made in the early years of the Roman empire, many think of Hellenistic statues as rare surviving originals. There are no originals besides the wax and clay models around which moulds were made. The only reason Lysippos could make 1???500 works was because he was forging parts from moulds and existing pieces that could be mixed and matched with newer ones.

The later marble copies of his works and those of fellow artists provide an echo of artistic accomplishments of the time. So popular was the form that it spread east, occasionally manifesting regional variations, as with Eros Riding a Lion, discovered in Yemen in 1953, which was cast from a thicker mould and depicts a lion bearing a pointier mane than found on statues closer to Greece.

“With the spread of classical culture to the Near East, we have a popular style and medium emulated by people across the world”, including pieces in Iran and Iraq, which are not part of the show, Lapatin says. Discovered in Bulgaria in 2004, the Portrait of Seuthes III is a pristine head of the Odrysian ruler, noteworthy for its lifelike, almost watery-looking eyes and intricately carved hair. “The huge beard and very intense look, the technique is done in the Greek manner, no doubt an itinerant craftsman who is adapting his work to a local patron.”

Artwork with a timeless quality

Among the most famous bronzes from the period is Boy with Thorn, or Spinario, dating to 50BCE. It has been copied many times over the centuries, notably a marble in the Medici collection, and provided inspiration to Renaissance artists like Michelangelo and Masaccio.

“The Spinario has become a symbol of ancient Rome,” says Daehner of this lifelike portrait of an unassuming boy seated on a rock, examining the sole of his foot. “What intrigued artists for so many centuries was that it had this timeless quality, a moment of a boy being self-absorbed, and you’re allowed to witness what he’s doing while he doesn’t notice you are there.”

Aside from the near-totemic number of reproductions, the Spinario might be the only bronze to survive 2?300 years above ground, noted first in the 1160s atop a column outside the Lateran Palace in Rome. As ubiquitous as bronzes were, most in the collection were saved by natural disasters that covered and protected them from eventually being melted down to make jewellery, coins and weaponry. The large number discovered underwater indicates frequent commercial transit and a thriving art scene similar to modern markets, with connoisseurs, commissions, dealers and patrons.

The Colossus of Rhodes was financed from a cache of weaponry abandoned by fleeing Cypriots after being routed by Ptolemy I’s forces in a fourth-century siege. In 653CE, its pieces were sold to a merchant from Edessa (in modern-day Turkey), who is said to have loaded them on to 900 camels. There’s no telling what happened to them after that, but chances are they were melted down and the Sixth Wonder of the Ancient World was reduced to jewellery, coins and weaponry. – © Guardian News & Media 2015

Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World is at the Getty Centre in Los Angeles until November 1