The vice0chancellor of the North-West University

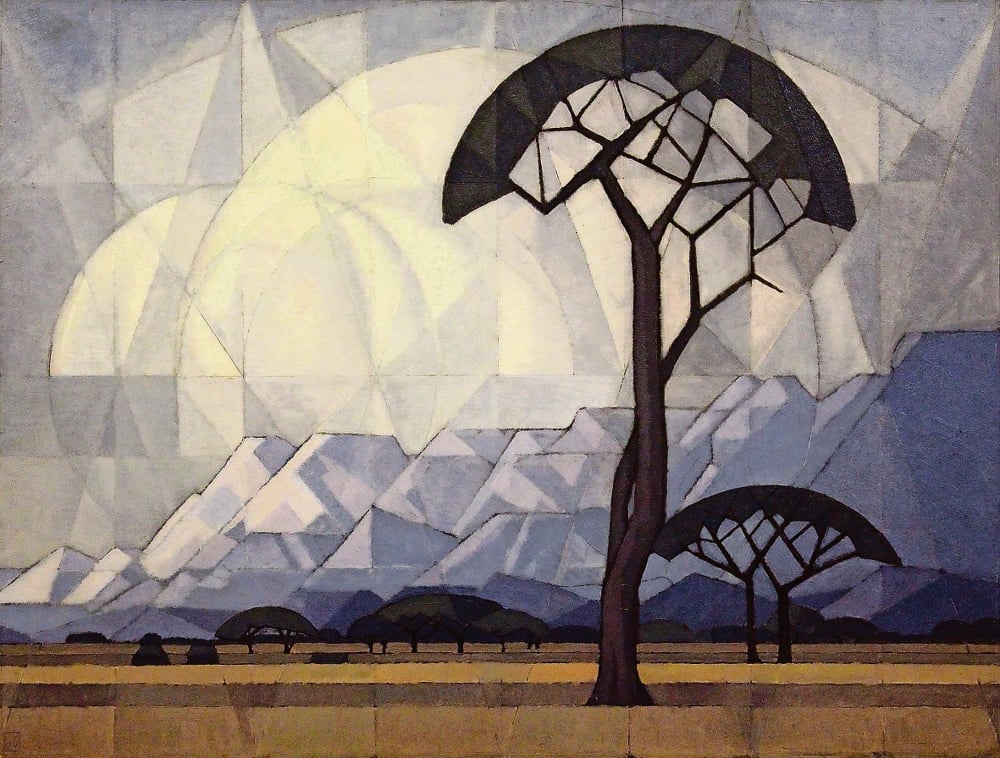

As you walk into the upper area of Johannesburg’s Standard Bank Gallery, the large paintings that dominate the space strike you with their sheer beauty. These works by South African artist Jakob Hendrik Pierneef show the magnificence of our land. But you cannot view A Space for Landscape without being subjected to values that might leave you bewildered.

The backdrop against which this exhibition takes place includes the #RhodesMustFall movement and, at a more sinister level, the Islamic State’s violent destruction of ancient sites in Palmyra.

The gallery is so keenly aware of the vulnerability of this displayed culture that you’re obliged to leave your handbag in a little locker in the gallery’s vestibule. Denuded, hopefully, of tools you could use to damage or deface the work, and armed only with the key to the locker in question, your eyes and your heart, you enter the space.

But can you strip yourself also, in a similar gesture, of political bias? Curated with clear savvy about how loaded but also how aesthetically pleasing this collection of paintings, drawings and intaglio prints by Pierneef (1886-1957) is, this brave exhibition poses questions and skirts assumptions about the proper source of beautiful art – or if beautiful art can be understood to have a source that is “proper”.

Much as we might like to believe that beauty is created by nice people with unquestionable morality, we cannot. The conundrum about whether art can be isolated from its political context, or whether it is a clear voice of the ideological values of the artist who makes it, is messy and insoluble.

Pierneef was a card-carrying racist. Until 1946, he was a seminal member of the Broederbond,movement that espoused the reprehensible thinking that was the kernel of the apartheid regime. Is his art about politics? Arguably, it is much bigger.

An exercise in beauty

This astonishingly fine collection of his work is by no means comprehensive, but curator Wilhelm van Rensburg has chosen a body of material, drawing from both private and institutional collections, that offers you an understanding of the breadth and ambit of the paintings. Hung for visual effect rather than in a chronological order, they are placed to resonate with one another colouristically rather than pretending to be an historical overview. Looking at this exhibition thus becomes an exercise in beauty: it does not allow history to rule lines around any of what you’re looking at.

The works hit you in the solar plexus: the overwhelming power is that of the South African landscape, coloured as it is by majestic mountains, and the inescapable light, very specific, harsh yet gentle, and often handled in a Venetian yellow: a hue not bright or brazen, but direct and pervasive, like the Highveld winter grass or sunlight.

Composition in Blue

Pierneef’s line is fluid, almost musical, as it echoes the Art Nouveau values of William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement of the time, or the geometric that artists such as Piet Mondrian were playing with in their own work. These are a painter’s paintings; there is no attempt to make them look like photographs – outlines are bold, colour is flat, linework almost decorative. There’s a time-hewn deliberateness about them.

His compositions glory in the rise and fall of a valley and the majesty of deep space. The architecture of cumulonimbus clouds and the filigree in Karoo thorn trees make your head buzz and your heart sing.

So, yes, you might take a step back and recall that the genre of landscape grew out of a seed that spoke of pastoral ownership and that Pierneef’s paintings were in celebration of an understanding of a people’s chosenness in Broederbond thinking.

Celebrating the land

But in a sense the sublime and unequivocal skill with which he has rendered the Waterberg, scenes in Pretoria, snippets of the Free State or Marabastad, supersede these political gestures.

Pierneef celebrates the magnificence of the land and, in the face of his wonderful work, and with many years of political struggle and democracy behind us, the political veneer becomes almost petty. Or does it?

Each painting sings to you the songs of this country’s natural gorgeousness but, as you walk by, the main effect is the silence of the works. It is only the very early pieces, produced in the 1920s in Europe, when Pierneef was a young man learning the craft of his art, that people appear. It is a curious reality that the work that Pierneef created at the height of his prowess are supremely unpopulated. He didn’t celebrate South Africa’s people, he celebrated the land itself.

A low point in the exhibition is the so-called iconoclastic work in the central downstairs space. Comprising derivations of Pierneef by South African artists of the ilk of Wayne Barker, Monique Pelser, Michael MacGarry (carrying the mantle of the Johannesburg-based visual art collective Avant Car Guard) and others, their work cannot be seen isolated from Pierneef’s. On their own, they become self-indulgent and unconvincing, in-house jokes that resonate only with the cognoscenti. Landscapist Carl Becker’s works feel bruised in the forced comparison with Pierneef’s.

In a sense, this exhibition reveals the gallery’s structure as flawed. The works upstairs are so powerful that you want to leave the space without allowing visual clutter to hamper your perceptions. You don’t want to see the downstairs aspect of the exhibition before you head home.

A Space for Landscape: The Work of JH Pierneef, curated by Wilhelm van Rensburg, is on at the Standard Bank Gallery in central Johannesburg, until September??12. Phone 011?631?4467 or visit standardbankarts.com