Teenagers in Cape Town who live in poverty and face a bleak future are turning to pangas

"It's like a soccer score," says a Vatos gang member in Khayelitsha outside Cape Town, using his hands to explain the killings. He is in matric. "Now the score is 1-1. We want it to be 3-1 to us."

The 19-year-old squints up at the sun, chewing on a matchstick. Seven of us are sitting on beer crates behind an RDP house in Greenpoint – not the trendy Cape Town suburb, but one of Khayelitsha's poor areas. One of them – they do not want to be identified – chases away an inquisitive child. "Hamban', hamban'." House music pumps from a parked car nearby.

But in the game of teen gang warfare in Khayelitsha there are no winners. The death toll in the Cape Town township this year rose to five in the early hours of a recent Sunday morning after a teenager was stabbed to death. The violence is spreading to other townships.

"We will kill the Vuras if they come here," the gang member says, dragging a finger across his throat to the laughter of his fellow gang members.

They join gangs to gain popularity and respect. They join so "the chicks scream for [them]". But as in other poor places around the world, their reasons are rooted mostly in deep socioeconomic problems.

Many also join for protection. They know they can be attacked simply because they live in a particular area.

All of them have knives or pangas, ready for the next fight.

Attacked

Two of those speaking to me have dropped out of school because they are afraid they will be attacked by rival gang members at the same school.

Being a gangster can be an every- day-of-the-week thing. Except on Sundays when these seven gang members go to church.

They describe gang fighting as "wrong", but their rationale is simple. "He has a knife and I have a knife. If we fight and I kill him, then okay. If I die, then I die, it's fine," one says matter-of-factly, while he casually throws a stone at a dog.

Some gang members use dagga recreationally, others tik. But they do not deal in them. Teens as young as 13 are recruited to grow the numbers – not to be trained in the intricacies of drug running.

These gangs are defined by geography. Vuras and Italians can be found in sections B and C. Their rivals – Vatos, MDCs and Hard Livings – are found in Greenpoint and sections A to J.

They are not organised. All they have is a name, a hand signal and an enemy. As far as we are told they do not have guns. Their leaders are whoever was at the front of the group in the most recent fight, whoever was not "surrending" (sic), whoever did not run away.

Their clothes are clean and ironed. Their eyes are clear.

Stab wounds

Ducking below a clothesline, two more join us. They smile and respectfully greet me and the interpreter, a community member, who tells them to "show your faces, don't hide".

One says "nice smile", and they cling to each other laughing.

When I ask to see one member's 17 stab wounds from an attack that made him join the gang, they help him to take his T-shirt off, lifting it over his head, to show the star-shaped scars spread over his back and shoulders.

It is hard not to notice the raised pale stab scars on the neck of another.

A gang member displays the scar from a stab wound. (David Harrison, MG)

But they stop laughing when they describe the anger they feel when walking to a meeting point for fights. "When you see that person who stabbed you … Aha."

They are not laughing when I ask, if they could, would they walk away from this. They all say yes, "but there is no plan to stop it".

"You can feel sorry for us because we are in this now. Write the story and try to understand," says one.

Another asks for help in changing schools. A third asks for R2 to buy a cigarette.

Playing truant

Some schools in recent months have been temporarily closed because of fighting on or near school property, according to local non-governmental organisations. Many pupils, even those not aligned with a gang, play truant because they fear they will be attacked on the way to and from school.

These teenagers lack the support and guidance of parents, who travel far and work long hours, and they have almost no access to after-school activities. They are exposed to vigilantism, domestic violence and furious service delivery protests. They are also influenced by stories of epic battles between traditional Cape Flats gangs and fight scenes in the controversial TV series Yizo Yizo.

There have been at least 14 vigilante mob killings in Khayelitsha during the past nine months. Policy co-ordinator for the Khayelitsha-based Social Justice Coalition Gavin Silber says: "The community has clearly lost faith in the police to keep them safe and, in their desperation, are taking the law into their own hands."

The mother of an ex-Vato gang member stopped her son from attending the Sizimisele Secondary School three weeks ago after she heard that rival gang members "wanted him". He spends his days mostly indoors. "Ayindiphathi kakuhle," he says – it doesn't feel right.

He has seen several stabbings, which were like "it was happening to me". "The way he cried when they were holding him and stabbing him … and the way he moved …" he recalls one such attack.

Teenagers join gangs "because they enjoy the fighting", he says and they can write the name of their gang on their school bag. "But a lot of them join not understanding how serious this is, that someone will actually die, and that it might be them."

In the yard of their RDP house, his mother wipes her hand across her chest repeatedly, saying: "I don't know, I don't know, I don't know."

If her son wants to walk to the local spaza shop, she walks with him. She does not know what she would do if he was attacked then. "Shoo, andiyazi," she says, clicking her tongue.

She walked us out. "I sleep at night because God loves me," she says loudly, looking at the sky.

Man of the house

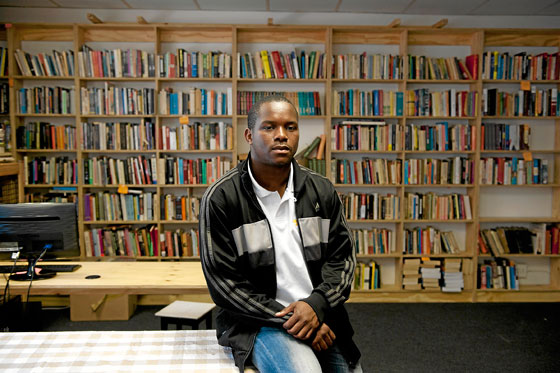

Sifiso Zitwana works in the city. He is in his early 20s but he is already the man of the house. He took over when his mother died in 2010. His father is not around.

He decided to send his 17- and 18-year-old brothers to the Eastern Cape after a gang came to their house in Greenpoint one night "to kill".

"That was me, finished. The next morning I put them on a bus to the Eastern Cape," Zitwana says.

Sifiso Zitwane sent his two brothers to the Eastern Cape after all other attempts to get them out of gangs failed. (David Harrison, MG)

"These kids want to be the boss, they want to be known in the community," he says about the gangsters. His brothers also wanted to be the boss. The 18-year-old said to Zitwana one night: "Why should I run in my own community? I must fight."

Zitwana tried to reason with them, took them for counselling and even hit them, once drawing blood, but they continued with their gang activities.

The boys now live alone in the Eastern Cape and they complain about teachers using "heavy" corporal punishment. At least it is safer there than in Khayelitsha.

But Zitwana misses them. "It kills me when I think of them down there."

Fights in the corridors, stabbing at the gate

It is not easy being the principal of a school where there have been fights in the corridors and a pupil was stabbed at the school gates.

An imposing man, Bongani Mfikili, the principal of Thembelihle High School, fills the chair behind his desk. He recently called in a pupil who is a known gang member, only to have his office set alight one night shortly afterwards.

But he has persevered and understands that teenagers join gangs out of "hopelessness and frustration".

A pupil interrupts the interview to hand in his work. A teacher outside tells me the pupil was made to sit in the foyer "because he wanted to fight the deputy principal".

Mfikili has been meeting troubled pupils and their parents to encourage them to discipline their children, although he knows that some parents tell their children: "If you do that again, I will report you to the principal."

"We are like prison warders here," he says.

He phones the police for help when his pupils are too scared to walk home after school, and he complained so much to the education department about teenagers from other schools "jumping the fence and going from class to class hunting" that the school was eventually given private security guards.

It's not easy being the principal of Thembelihle High School where gang fights happen in the corridors. But Bongani Mfikili understands pupils' frustrations with their everyday lives. (David Harrison, MG)

While admin staff walk in and out of his office, Mfikili speaks about the muti called amakhubalo. It is bought from sangomas and involves a live chicken and a nip of alcohol. It makes them "want to fight and have a quick temper".

"When the spirit enters the classroom … learners run around screaming … some say they roar like a lion."

About 20 pupils have left the school this year because of the violence.

The "fashion" of teen gangsterism, as some have described it, has spread to Kraaifontein, about 30km from Khayelitsha.

"I first heard about it in March but things are becoming hectic now," a youth group facilitator for Equal Education, Zintle Makoba, says.

"Some schools close early for the day because of the fighting … You see big groups of kids walking together with weapons," she says.

Extreme measures

The principal of Masiyile Secondary School in Khayelitsha, Sisa Sodlaka, has resorted to extreme measures to regain control of the situation. Holding meetings with violent pupils and their parents was not enough.

"We also involved taxi drivers who came to speak to the pupils and threatened to sjambok them if they carried on fighting," he says, speaking quickly and interrupting himself to give orders at the door of his office to his staff.

He sought help from the police, giving them the names and addresses of pupils whom the police then "went to visit".

Although Sodlaka says discipline at the school is now adequate, some pupils appear to disregard authority. "If you hate me, fuck off, hate your mother first" is written on one pupil's backpack.

"Introduce, sir, introduce!" some shout in the face of a teacher accompanying me around the school. Others lean out of windows whistling.

Axolile Notywala, a researcher at the Social Justice Coalition, grew up playing soccer with boys who are now gang members.

"I think they finally found something that they think is fun," he says. "At first they might not have thought of the circumstances and as people got hurt then revenge was [sought] … it created a snowball effect."

About a month ago Notywala and his colleagues watched police chasing gang members down the road outside their Khayelitsha offices, shooting bullets into the ground at their feet.

Parents intervention

Parents are not supervising their children and are scared to "pull [them] out of shebeens and gang fights", director at Khayelitsha's Empilweni mental health centre, Mhongwe Mtshotshisa says. "If you shout at your child when they are seven, then at age 15 they will be telling you to shut up."

"It's the parents' fault that they are giving these kids the control, uyabona?" the centre's director, Mhongwe Mtshotshisa, says. The roar of taxis and buses outside the group therapy room almost drowns out her voice.

When they were children, says the centre's service manager, Donald Mfuniselwa, they knew, "when the street lights came on, I had to go home".

Khayelitsha in Cape Town: the home of violent teen gangsterism. (David Harrison, MG)

But it was difficult for parents to offer the emotional support their children need because just "feeding their children is hard".

"They go to work at 6am and come back at 6pm … they leave for the city probably to look after someone else's kids," he says.

There is an emptiness left by dysfunctional families, often fatherless, and inadequate schools. Teenagers are searching for a sense of security and comfort.

"Your fellow gang member will jump to defend you, even stay away from school to protect you," says Mfuniselwa. "Can you imagine what that must feel like to a teenager who is unhappy at school and at home?"

All teenagers, regardless of where they come from, "have a fight to fight", Mtshotshisa says.

"In good schools where there are sports resources, boys will fight their fights on the rugby field. In Khayelitsha, they fight their fights with pangas."

Delimited

Equal Education deputy general secretary Doron Isaacs says gangs provide a sense of belonging but cannot be compared with rugby.

"In rugby, the violence is delimited. Here it is not – over half a dozen kids are dead this year. They join knowing this is possible or likely.

"Why do they court death? Why would a middle-class child almost never do this?"

When your dreams seem impossible to attain, then life loses meaning and value.

"When your dreams seem attainable … then you have your fun, but you also keep your head down and work hard. If you can afford a PlayStation, you get your blood sport on a flat screen, not on the streets."

It is not surprising that children in Khayelitsha are killing and dying, he says, but what is surprising is that "many still have hope, study hard in school, and are active in organisations like Equal Education, believing that things can change".

What is government doing?

“You should watch people debating about this. They never find a solution. Everyone calls for ‘Action, action!’… What action?,” said Sifiso Zitwana, letting his hands fall heavily on either side of his chair. He works for a not-for-profit organisation, Ndifuna Ukwazi, in Cape Town.

Last week the City of Cape Town, in consultation with the provincial education department and the department of community safety, launched the School Resource Officers pilot project.

Six schools in the province will each be assigned a Metro police officer to “co-ordinate and improve on existing school safety initiatives”. The project will run for a year, after which it will be reviewed for roll-out to more schools.

But what is being done to ensure the immediate safety of the over 60 000 pupils at Khayelitsha’s 58 schools?

The South African Police Service (SAPS) says it recently launched Operation Protect Khayelitsha, which saw the additional deployment of police officers to trouble zones. It says that any “individuals or groups” who commit crime will have to face the “full force of the law”, including those younger than 18 who, despite popular community belief, will “have to face the consequences of their actions in court”.

The police have been approached by schools to "visit" young members at their homes and pull them into line. (David Harrison, MG)

It would not confirm how many teenagers have been killed in the fighting so far this year.

The provincial education department has “liaised with the SAPS to conduct search and seizure operations at schools” and has also encouraged schools to conduct their own search and seizure operations.

Although hundreds of teen-agers are reported to be part of these gangs, only seven cases of gang violence had been reported to the department this year, the provincial MEC’s spokesperson Bronagh Casey said.

The provincial cultural affairs and sport department has opened more than 100 mass participation, access to opportunity and development centres, six of which are in Khayelitsha. Also a pilot project, it will provide “after-school sport activities to youth… [and] an alternative to the getting involved in anti-social behaviour”.

Addressing the widespread loss of faith in the police, Western Cape premier Helen Zille, announced in August the appointment of a commission of inquiry into “allegations there was systemic failure by the SAPS in Khayelitsha to prevent, combat and investigate crime, take statements, open cases and apprehend criminals, resulting in a breakdown in relations between the community and the police”. — Victoria John