The Mzansi Ballet performs at the SAAF Museum Air Show's 40th anniversary on May 11 2013 in Pretoria

In recent months Uganda and Nigeria attracted international attention when they decided to tighten laws criminalising homosexuality. Allies by circumstance, Muslims and Christians joined forces in the witch-hunt for gays, and some politicians found it far easier to designate a scapegoat for voters than to provide rice and ideas. Today, 38 of the 54 African countries condemn homosexual behaviour.

For many gays and lesbians, South Africa stands out as a safe haven. That is, until these refugees find out that it is not exactly the haven of tolerance they had dreamed of.

Tiwonge Chimbalanga (25) comes from Malawi. Known as Auntie Tiwo, this trans woman lives in OR Tambo village, near Cape Town’s Gugulethu township. She was jailed at the end of 2009 by the Malawi police for organising a marriage ceremony with her partner Steven Monjeza. But following an international outcry and an intervention by the UN Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon, the couple was pardoned by then-president Bingu wa Mutharika and released a few months later.

Monjeza remained in Malawi, where he married a woman, but Tiwonge fled to Cape Town. Four years later, perched on golden heels and compulsively giggling, she says: “It’s cool here. It’s a nice country. There is freedom of expression and freedom for LGBTI [lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex] people.”

But a few minutes later, Tiwonge concedes that she hardly ever ventures off the block. She has been beaten three times since she got here, and she is still scared.

Unknown number

No precise figures exist on the number of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender refugees in Africa. Neil Grungras, who founded the Organisation for Refuge, Asylum and Migration, an advocacy group for refugees fleeing persecution because of sexual orientation or gender identity, says: “A vast majority, perhaps 99%, will never try to escape. Because they’re terrified to migrate, they don’t have a passport, the money or they don’t speak another language …” Only the wealthy flee to Europe or the United States.”

If they had the means, Grungras believes, there would be “hundreds or a few thousand” gay refugees migrating to South Africa.

But one thing is certain; their number is increasing, as illustrated by Guillain Koko, a human rights lawyer from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and refugees rights organisation Passop’s (People Against Suffering, Oppression and Poverty) LGBT project co-ordinator. The organisation has already received about 200 requests for assistance this year; that is the same number as for the whole of 2013.

Either through shame or fear, these refugees often do not display their sexuality and identify themselves to the South African authorities as mere economic migrants.

Widespread among immigration officers, homophobia sometimes makes the situation untenable, especially for transsexuals, as Koko reports: “When they are in the women’s queue, the women chase them down. When they go to the men, they get booed. And instead of helping them, the guards laugh at them and beat them up. In the end, many do not even reach the window of the immigration office.”

Ahead of the pack

It’s worth recalling that, in 1994, South Africa was the first country in the world to condemn explicitly discrimination because of “sexual orientation” in its Constitution. “We knew that we had achieved one big victory but that it was still a victory at the start of a long road ahead,” remembers Edwin Cameron, an openly gay judge at the Constitutional Court.

“Legislative reform preceded the evolution of mentalities,” he says: “It’s not perfect,” he adds, “but it’s certainly better than elsewhere in Africa. There’s no doubt that things are enormously better for a Zimbabwean, or a Ugandan, or a Nigerian who comes here.

“There’s no criminal offence, there’s no arrest on the fact of being gay, there’s free association, there’s the ability to have same-sex relations. […] Maybe their expectations are too high. Maybe they think that they’re going to come to the land of golden equality. Well, we’re not a land of golden equality. We’re a land where there’s still ignorance, there’s still discrimination, there’s still hatred. But we’ve made more progress in public attitudes than any other country in Africa.”

Cameron’s assessment is backed up by the last Pew Research Centre survey, which found that 32% of South African citizens think that homosexuality should be accepted by society, compared with only one or two percent of the population in the rest of Africa.

If Johannesburg and Cape Town do have bubbles of acceptance, the fact remain that, 20 years after the end of apartheid, homophobia and xenophobia are still rampant, especially in the townships.

Fleeing in fear

Jean-Claude Puati-Bazola fled the DRC in 2007 fearing for his life because of his sexuality. Upon arrival, the gay youngster spent two weeks in Pretoria to get his asylum seeker certificate, while expecting a refugee status permit, a document that currently trades at about R2 500 in bribe money, according to a well-informed source.

“It was really the struggle for survival,” says Puati-Bazola. “We were thousands and thousands to [a]queue. People were fighting to get the best place. It was terrible.”

He then discovered the shelters. In spite of good intentions, these places are often inadequate: they welcome migrants for only two to three weeks and are located in dangerous areas.

Jean-Claude Puati-Bazola, a gay refugee from DRC, is off to Iceland. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

Jean-Claude Puati-Bazola, a gay refugee from DRC, is off to Iceland. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

For seven years, Jean-Claude ran from shelter to temporary accommodation. He spent his time changing jobs. As soon as an employer discovered he was gay, he was shown the way to the nearest exit. And in the streets people would throw stones at him, calling him names like “moffie”, until he was assaulted in 2012 by a man who strangled and robbed him. That was too much. He has decided to turn the page and move to Iceland.

“Everything I do here is not to live but to survive,” he says. “So I decided to go and live in another country where I can fully develop myself.”

Rape victim

Raped in Gabon, Jean-Yannick* left his small restaurant in Port-Gentil in his home country, and arrived in Cape Town just over a month ago. When he landed, he still held fond memories of previous holidays in South Africa’s southernmost city, which travel brochures have been selling for a few years as the gay-friendly spot in Africa. Indeed, the De Waterkant nightlife would even be the envy of the French partygoers from the Parisian Marais.

But Jean-Yannick discovered that it just took a 15-minute drive to the suburbs to realise that this crazy “freedom” only concerns a white and wealthy minority. The most publicised, though, as can easily be seen during the Cape Town Gay Pride.

Jean-Yannick from Gabon discovered that racism is rampant in Cape Town’s gay clubs. (David Harrison, M&G)

“Here, the law covers me, but it is not easy,” says Jean-Yannick, as gentle as he is refined. “I’m not a transsexual you know, I’m gay and I just have dyed hair, but here I’m the devil! In the train, I draw a lot more looks than the South African transsexual who is next to me. And that’s because I’m a foreigner!”

Did he experience the downtown nightclubs? “I went there twice,” he admits. “I saw that there was still racism in the gay world. Nobody approached me because I was black. And they looked at me with the air of saying: ‘He’s black and gay, he has all the defects of the world!'”

‘Corrective rape’

In the township of Khayelitsha in Cape Town, gay people keep a low profile. Especially lesbians. South Africa is sadly known for the phenomenon of “corrective rapes”, which is based on the belief that if a lesbian woman is raped she is then “cured” of her lesbianism and is accordingly made straight.

“We knew we would get you one day,” her assailants said to activist Funeka Soldaat (52) in 1995 while raping her in a field. “In townships, men think being a lesbian is un-African, that lesbians are taking their girlfriends and that they have to prove that they are men and that you are a woman. But it’s a stupid competition!”

It’s already so difficult to live as a lesbian that she can’t even “imagine being gay and also a refugee in a township. That cannot work.”

For three years, Soldaat has been fighting alongside organisations such as Amnesty International for the South African police to investigate the murder of Noxolo Nogwaza, who was raped, stoned and stabbed in April 2011 because she was a lesbian. But nothing came of it.

Whereas Cameron proposes to create a special unit for LGBTI crimes, Amnesty International, which usually “doesn’t believe in hate crimes”, decided to make an exception. Its Southern Africa director, Noel Kututwa called for specific legislation, “because of the strong intolerance and the unique situation in South Africa”.

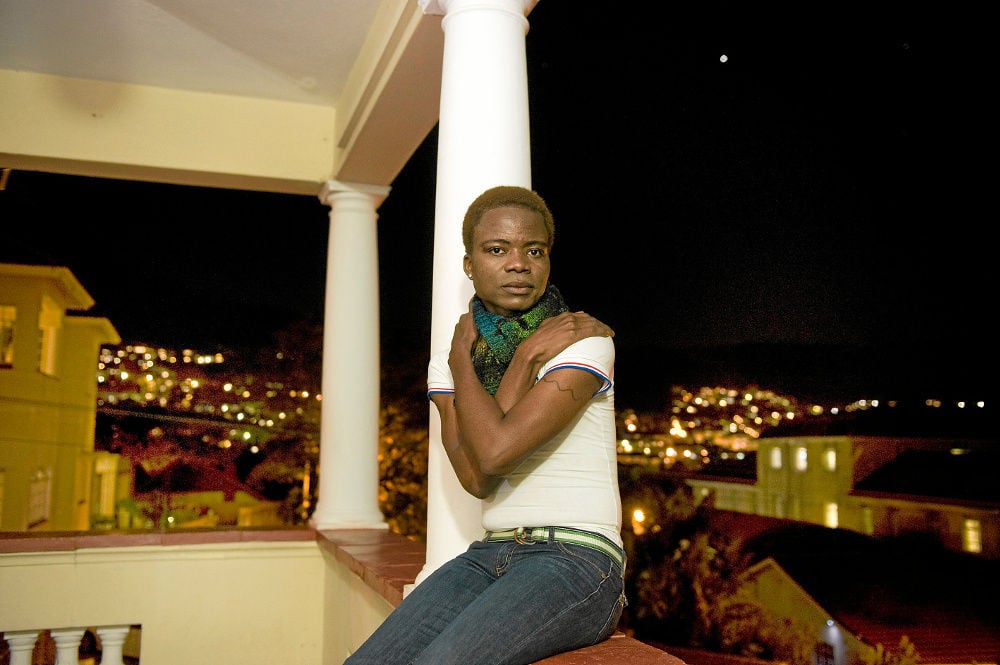

Tino, a gay refugee from Zimbabwe, came to South Africa hoping he could finally be open about his sexuality. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

Tino, a gay refugee from Zimbabwe, came to South Africa hoping he could finally be open about his sexuality. (Madelene Cronjé, M&G)

Walking the streets of Braamfontein in Johannesburg with his white and grey Teddy jacket, Tino* looks like an American student. But he is not.

In 2007, at age 18, he left Zimbabwe. “At that time, what we were hearing was that in South Africa, when you are gay, it’s the best place to be. I thought, maybe there I could express my sexuality.”

Seven years later, Tino reviews the situation with lucidity: “Here, it’s not 100% safe, it’s not even 90%, but in Zim, it’s worse.”

*Not his real name.