Ever since Thomas Duncan, the first Ebola patient diagnosed in the United States, got on a plane in Monrovia and travelled to Dallas with the virus incubating in his body, there has been a lot of confusion about the risk of contracting the disease during travel. Now, with the news that the second Dallas health worker to contract Ebola flew from Cleveland the day before reporting to hospital with a fever, worry about the virus during air travel is likely to peak. Here’s a guide to how you can and can’t get Ebola on a plane (or, for that matter, anywhere else).

Ways you can get it

- You can get the Ebola virus if you have direct contact with the bodily fluids of a sick person, including blood, saliva, breast milk, stool, sweat, semen, tears, vomit and urine. Direct contact means these fluids need to get into your broken skin (such as a wound) or touch your mucous membranes (mouth, nose, eyes or vagina).

- You can get Ebola on a plane by kissing or sharing food with someone showing symptoms of Ebola. You can get it if that symptomatic person happens to bleed or vomit on you during flight and those fluids hit your mouth or eyes. You can also get it if you are seated next to a sick individual, who is sweating profusely, and the sweat touches your face. But this is unlikely. One of the Ebola discoverers, Peter Piot, said: “I wouldn’t be worried to sit next to someone with Ebola virus on the tube as long as they don’t vomit on you or something. This is an infection that requires very close contact.”

- You can become infected by having sex with someone infected with Ebola. This means you can get Ebola on a plane if you join the mile-high club with an Ebola-infected individual. The virus has been able to live in semen for up to 82 days after a patient became symptomatic, which means sexual transmission – even with someone who has survived the disease for months – is possible.

- You can get Ebola through contact with an infected surface. Though Ebola is easily killed with disinfectants such as bleach, if it isn’t caught it can live outside the body on, say, an armrest or table. In bodily fluids, such as blood, the virus can survive for several days. Thus, if someone with infectious Ebola gets his or her diseased bodily fluids on a surface that you touch – a plane seat, for example – and then you put your hands in your mouth and eyes, you can get Ebola on an plane.

- This is a highly unlikely situation, but you can get the virus by eating wild animals infected with Ebola or coming into contact with their bodily fluids – on a plane. The fruit bat is believed to be the animal reservoir for Ebola and, when it’s prepared for a meal or eaten raw, people get sick. So you can get Ebola in flight by bringing some undercooked bat meat on to the aircraft and having it for supper.

Ways you can’t get Ebola

- You can’t get Ebola from someone who is not showing symptoms and is not already sick. The virus only appears in bodily fluids after a person starts to feel ill, and only then can he or she spread it to another person. If you were sitting on a plane next to someone who had Ebola but wasn’t yet showing symptoms (and therefore was not yet infectious) and you were exposed to that person’s bodily fluids, you would not get Ebola. The second Dallas health worker to contract the virus flew the day before she reported to hospital with a fever and had a temperature of 37.5°C (normal is 37°C). If true, it’s unlikely that she would have been infectious at the time but health officials are taking precautions and following up with everybody on the flight.

- It’s very rare to transmit Ebola through coughing or sneezing. The virus isn’t airborne, thankfully, and experts expect that it will never become airborne because viruses don’t change the way they are transmitted.

Still, the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offered this cautionary note: “If a symptomatic patient with Ebola coughs or sneezes on someone, and saliva or mucus come into contact with that person’s eyes, nose or mouth, these fluids may transmit the disease.” This happens rarely and usually only affects health workers or those caring for the sick.

Low chance of transmission

The possibility of transmission on a plane by coughing or sneezing exists but it is small. It would have to go something like this: an Ebola patient would have to cough on the hand of the person sitting next to them, releasing some amount of mucus or saliva. The person being coughed on would then have to, say, rub his or her eye with that hand, allowing the disease into the body.

The bottom line: Ebola is difficult, but not impossible, to catch even in confined spaces such as planes. Ebola isn’t easy to transmit. The scenarios under which Ebola spreads are very specific.

As the World Health Organisation, which does not recommend travel bans, put it: “On the small chance that someone on the plane is sick with Ebola, the likelihood of other passengers and crew having contact with their body fluids is even smaller.”

They also point out that people who are sick with Ebola are so unwell that they cannot travel. Ebola doesn’t spread quickly, either. An Ebola victim usually only infects one or two other people. Compare that with HIV, which creates four secondary infections, or measles with 17. So far, there have been three known Ebola cases originating in the US. There are more than 8 000 in West Africa. That’s where experts say the worry and fear about Ebola contagion should be placed.

Symptoms

The Ebola virus is a haemorrhagic fever that’s fatal in about half of all cases. Ebola typically strikes like the worst and most humiliating flu you could imagine. People start sweating and have body aches and pains. Then they begin to vomit and have uncontrollable diarrhoea.

These symptoms can appear anywhere between two and 21 days after exposure to the virus. Sometimes people with Ebola go into shock. Sometimes they bleed. Again, about half of those infected with the virus die, and this usually happens fairly quickly – within a few days to a few weeks of getting sick. The others return to a normal life after a months-long recovery period that can include hair loss, sensory changes, weakness, fatigue, headaches, and eye and liver inflammation.

There are five strains of Ebola, four of which have caused the disease in humans: Zaire, Sudan, Taï Forest and Bundibugyo. The fifth, Reston, has infected nonhuman primates only. Although scientists haven’t been able to confirm this, the animal host of Ebola is widely believed to be the fruit bat, and the virus only occasionally makes the leap into humans.

The current outbreak involves the Zaire strain, which was discovered in 1976, the year Ebola was first identified in what was then Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). The same year, the virus was also discovered in South Sudan.

“very rare”

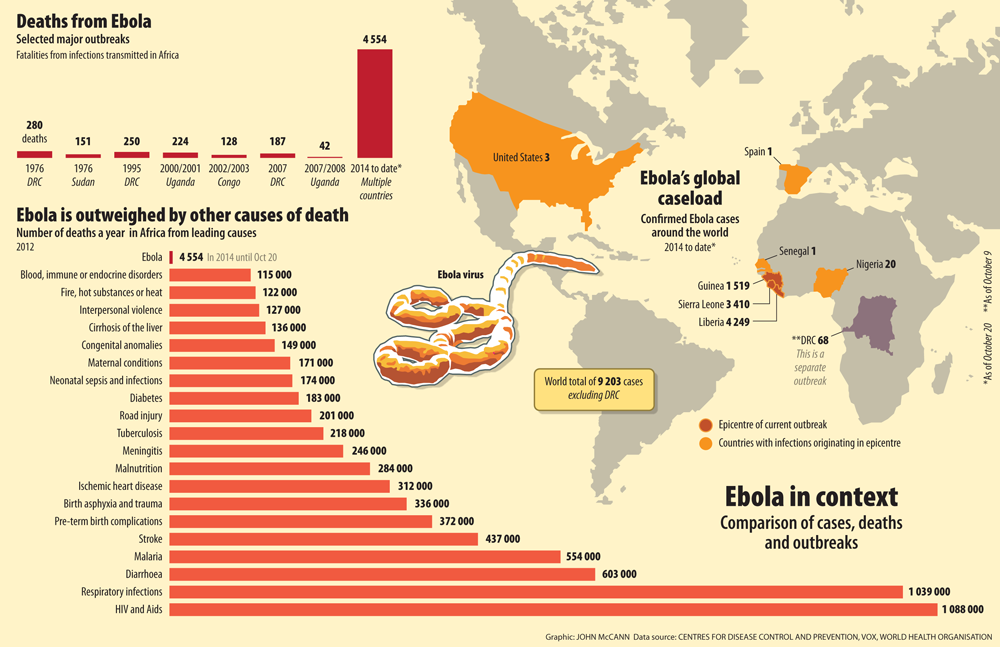

The Ebola virus is extremely rare. People are much more likely to die from Aids, respiratory infections or diarrhoea. Since 1976, there have only been about 20 known Ebola outbreaks. Until last year, the total impact of these outbreaks included 2 357 cases and 1 548 deaths, according to the CDC. They all occurred in isolated or remote areas of Africa, and Ebola never had a chance to go very far.

And that’s what makes the 2014 outbreak so remarkable: the virus has spread to five countries in Africa plus the US, and has already infected more than 8 000 people and has killed more than half of them. That is more than triple the sum total of all previous known outbreaks combined.

This article was originally published on vox.com. The original article can be found here

Travel restrictions and screening keep SA one step ahead

The scale of the current outbreak of Ebola viral disease in West Africa has led to mounting fears around the world, including in South Africa. Lucille Blumberg, the National Institute for Communicable Diseases’ (NCID) deputy director, said there was a chance of the virus being imported to South Africa, although the country was classified as low-risk.

“We are not talking about an outbreak in South Africa. But there is a chance of a traveller with Ebola coming into any country in the world,” she said.

The health department’s spokesperson, Joe Maila, said that, although the fear was understandable, preventive measures put in place by the health minister would minimise the risk of an Ebola outbreak in South Africa. “These measures include the screening that we do at airports,” Maila said.

Heat scanners have been placed at OR Tambo International Airport and Lanseria Airport in Johannesburg to identify travellers with temperatures, which is one of the symptoms of Ebola.

“At the time we had ascertained that Gauteng was the most vulnerable but our surveillance is ongoing and scanners will be put in place in Durban and Cape Town if the need arises,” Maila said. “We have issued travel restrictions – not bans – to and from the affected countries.

“We are appealing to the public to put off any nonessential travel to those countries until the situation has been stabilised.”

The advisory restricts travel between South Africa and Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. Even diplomats and healthcare workers travelling between South Africa and the affected countries need permission from the health department to do so.

Four countries – Nigeria, Senegal, the United States and Spain – had reported imported cases of Ebola, the NCID said in a statement this week. Since the outbreak was first confirmed by the World Health Organisation in March, more than 4 500 people have died from the disease, most of them in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Blumberg said: “The most important thing is that cases be recognised early. “Anyone dealing with a patient needs to be protected. We need to reduce the risk of spread, but we are not going to have an outbreak like they have in West Africa. We are quite prepared to prevent that from happening.”

According to Maila: “Although we are doing our best to prevent any cases of Ebola in the country, in the event that a case is reported, there are 11 hospitals in South Africa that are equipped to deal with the disease.

“These hospitals have been equipped with sufficient personal protection equipment to protect our health workers and the isolations facilities in these hospitals are adequate to be able to contain the virus. I can still confirm that there is no case of Ebola in South Africa. All of the suspected cases in the country tested negative for the virus,” said Maila. – Ina Skosana