The death last weekend of novelist and critic André Brink brings into the spotlight the writer’s considerable legacy in South African public life. He was an intellectual giant in a shallow local literary-critical pond, where (like Nadine Gordimer) he was often reviled as much as he was celebrated for his authorial pains.

The scale of his achievement, however, is altogether beyond dispute. Brink was a literary polymath of breathtaking range: he published, in Afrikaans and English, novels, plays, translations (of Shakespeare, Cervantes, Chekhov, Ibsen, Hochwälder, Camus, Henry James, Graham Greene, among others), scholarly criticism, edited collections, travel writing, and more.

Then, after his breakthrough on the world English market in 1974 with Looking on Darkness (Kennis van die Aand, dramatically banned at home in 1973), he morphed into a world novelist in English of enormous stature. Today, more than two decades after the liberation of South Africa from minority rule, a Google search on “Andre Brink” still brings up the phrase “anti-apartheid”, followed by the term “dissident writer”.

Like Alexander Solzhenitsyn, with whom he has often been compared, Brink’s recusant insider status vis-à-vis apartheid has held firm internationally. Brink has also been compared – by critics elsewhere, not the sniping locals, mind you – with Gabriel García Márquez, Toni Morrison and Albert Camus.

He was, to some extent, more populist than the duo of Gordimer and JM Coetzee, with whom he is often associated by readers and critics. His stories more readily played up the drama of oppression (for his local detractors, melodrama), its feeling (some would say sentimentally so), and its often violent sexual dimensions (at whose salaciousness the literati tended to sneer).

Like him or not, Brink made South Africa’s drama of oppression, and the quest for freedom, far more readable, in a pulp sense, than either of South Africa’s Nobel laureates ever did or could. Brink was particularly good at reanimating early-settlement slave stories, giving voice to forgotten victims in novels such as Philida (2012) and A Chain of Voices (1982), and vastly expanding the canvas on which South Africa’s stories of unfreedom played out in its literature.

Despite the uneven reception of Brink’s fiction, his literary-intellectual resources were nothing if not formidable. He had a vast range of reference and he was as well read as any comparative literature professor, publishing top-line academic books such as The Novel: Language and Narrative from Cervantes to Calvino (New York University Press, 1998), among others.

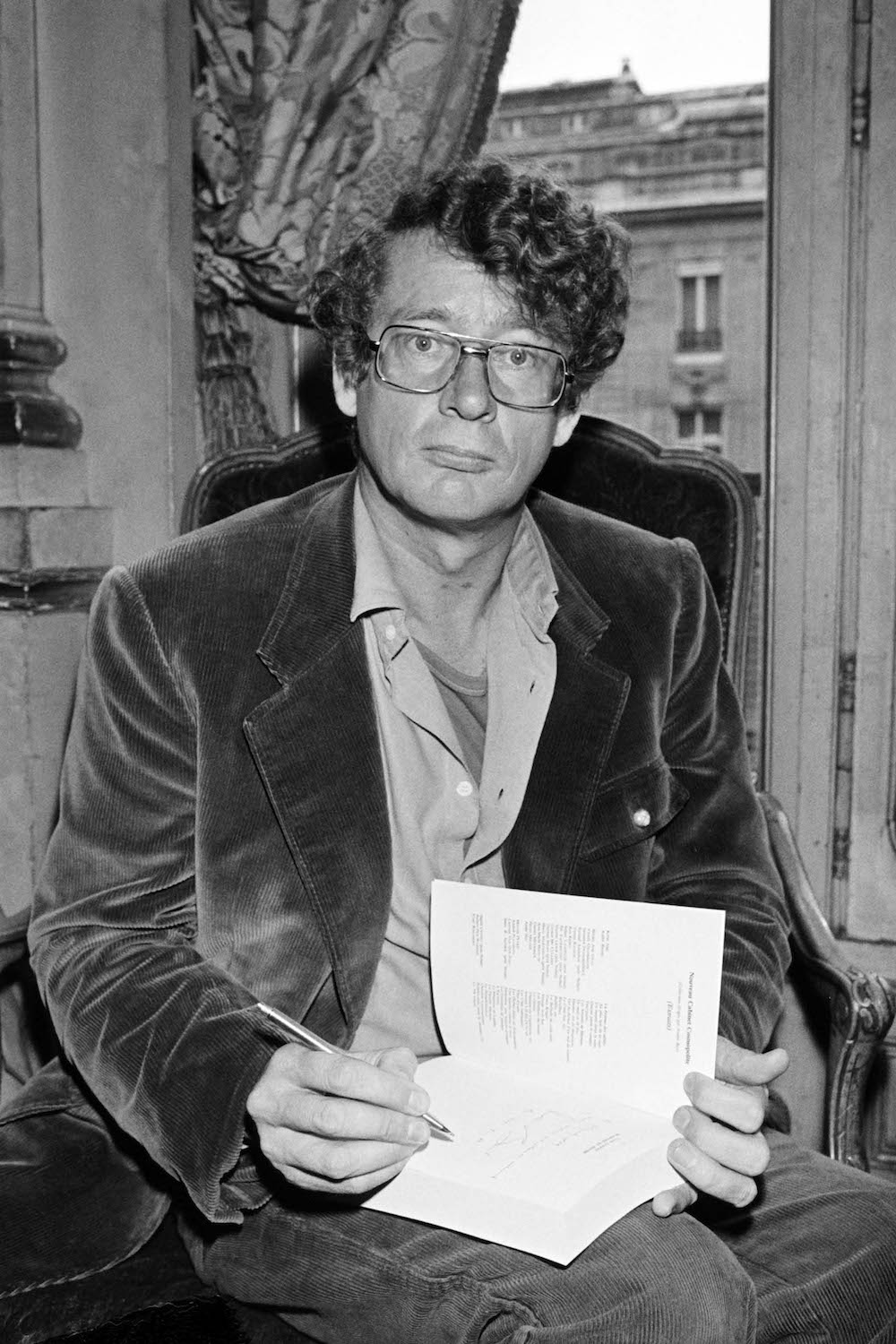

(Pic: Sophie Bassouls/Corbis)

He and JM Coetzee, close friend and fellow professor at the University of Cape Town for a time, curated the influential collection of writing, A Land Apart (Faber, 1987). In addition, two of his novels, An Instant in the Wind (1976) and Rumours of Rain (1978), were shortlisted for the Booker prize. His final novel, Philida – Brink’s 24th work of fiction – made the Booker long list, although prizewinning South African novelist Ceridwen Dovey, reviewing it for the New York Times, bemoaned its “disconcerting mix of violence and sentimentality”.

As if to rebut Dovey, Patrick Flanery, an American novelist with South African connections, praised it in the London Telegraph: “While this is a familiar story, it is one that must continue to be told, not least by white writers willing, as Brink is, to disinter the histories of complicity buried in their own ancestries.” Whichever way one leans, it is without doubt that Brink mediated the moral drama of racial oppression in South Africa in a way that Alan Paton, Gordimer, and even the English-speaking Coetzee intrinsically could not – from deep within the gulag of Afrikanerdom.

Unlike Coetzee, Brink was raised as an out-and-out Afrikaner. He was born in 1935 on a Free State farm (in Vrede); his memoir, A Fork in the Road (2009), engagingly tells the story of his conservative Afrikaner upbringing, and his eventual rebellion against it. Within the laager, Brink paid the price for his insubordination.

Coetzee has observed that during a certain period Brink “was in almost daily confrontation with the censorship apparatus”. Coetzee continues: “He was subjected to a degree of persecution, some of it simply small-minded, some of it quite chilling. Though I did not know him personally at the time [during the 1970s], it struck me that he responded with a great deal of courage and integrity, giving an example of how an intellectual should behave in confronting authority.”

This ostracising process followed Brink’s apprenticeship as one of the founder members of the Sestiger movement of Afrikaans writers, along with figures such as Jan Rabie, Uys Krige, Bartho Smit, Etienne Leroux and Ingrid Jonker – writers who scandalised the narrow ethos of official Afrikanerdom by writing about sex, race and religion, often in experimental modernist forms.

Outside the country’s borders, however, Brink’s career flourished. He began writing his novels simultaneously in English and Afrikaans, displaying a linguistic dexterity, which Gordimer confessed “amazed and impressed” her. According to the Guardian’s Nicholas Wroe, who profiled Brink in 2004, Brink often produced up to 14 drafts, resulting in two distinct books rather than an original and a translation. Brink’s dramatic stories did not disappoint his global readership.

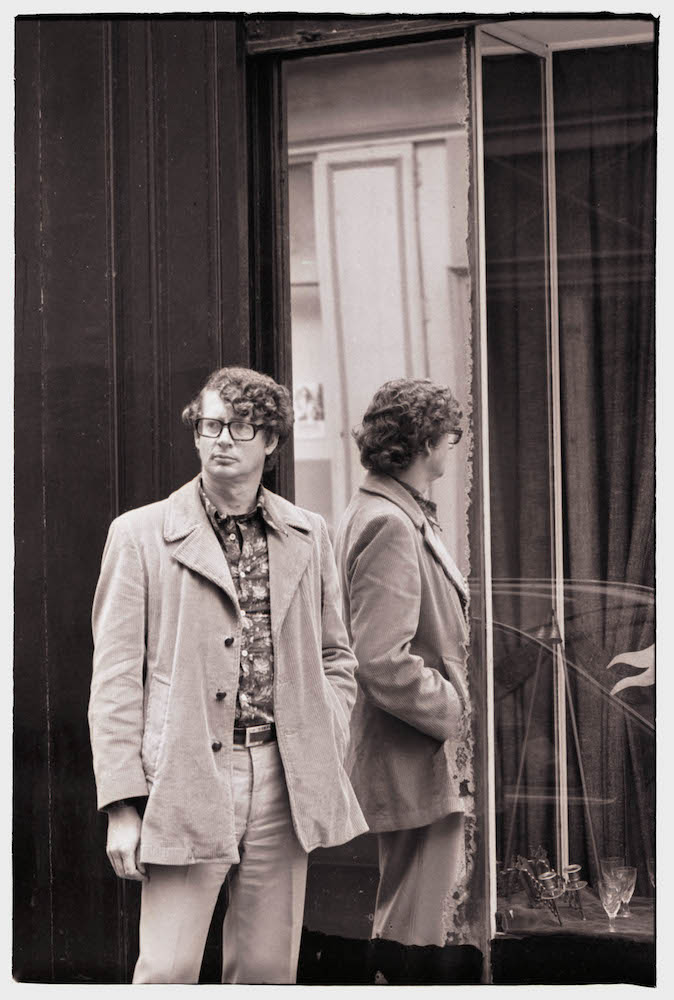

Sign of the times: André Brink won the foreign literature Medicis prize for his book A Dry White Season in 1980. (Michel Clement)

He wrote a string of “big” novels that found their mark in world literary reception. Apart from his two Booker short-listings, A Dry White Season (1979) won the prestigious Prix Médicis Étranger in France. He won many other literary prizes, both at home and abroad. Confirming his status as a global author, Brink has been translated into 35 languages, including an Occitan version of A Chain of Voices, published in 2011 (produced in Afrikaans as Houd-den-bek).

In this capacious book, Brink adopts William Faulkner’s technique in As I Lay Dying of giving expression to his novel through a series of linked monologues, in Brink’s case 30 of them (as opposed to Faulkner’s 15). Such literary ambitiousness was (and still is) not commonplace among South African writers. Brink, in addition, confronted the country’s most formidable representational problem, especially during apartheid – that of inhabiting the voice(s) of occluded black subjects who had largely been silenced during three centuries of racial oppression.

It remains open to debate just how successful such projects were. Apart from the usual academic charges of sentimentality and overwrought writing, the more important question is to what extent Brink is able to speak the voices of the oppressed without ventriloquising them, or speaking his own positions through them and in effect using such figures as prosthetic narrative devices. If this were the case, he would be perpetuating the implicit silencing of the colonising process.

Stellenbosch Afrikaans literature professor Louise Viljoen has investigated this question in a searching reading of four novels: An Instant in the Wind (’n Oomblik in die Wind, 1975/1976), A Chain of Voices (Houd-den-bek, 1982), On the Contrary (Inteendeel, 1993) and The Rights of Desire (Donkermaan, 2000). Viljoen’s verdict is ambiguous, finding that Brink does, in some cases, perpetuate, and even idealise, certain colonial stereotypes. In mitigation of this, however, she finds that Brink is acutely reflexive about the constructedness, both historical and authorial, of the voices he recreates in these works.

Nonetheless, this very “problem” marks Brink as a writer of an age that has now largely passed – the white apartheid writer-dissident excavating the country’s bad history. Even in what some regard as his finest “post-apartheid” book, The Rights of Desire (a conscious supplement to Coetzee’s Disgrace, which it references in its title), the story gestures to the inequalities of the past, and how they cause displacement in the post-apartheid present for the frustrated but desiring white protagonist, a retired librarian.

Where, one might ask, is the “new” democracy in all of this, with all its perversely novel problems? Still, when the “world literature” professors everywhere write up their curricula on “South African literature under apartheid”, Brink’s name will be right up there among the top five, at least. He served his country with great distinction and he should be read even more now that he is gone.

Leon de Kock is emeritus professor of English at Stellenbosch University, and senior research associate at the University of Johannesburg