It has been more than three years since the United Nations general assembly adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Mike Segar/Reuters)

South African cellphone giants are not only charging higher prices for data than those in other developing countries but, in general, they are also banking substantially more profit.

A comparison of 10 telecoms companies in India, Nigeria, Mexico, Brazil, Egypt, Kenya, Morocco and the United Arab Emirates shows that service providers in many of them glean significantly less profit than South African giants MTN and Vodacom.

The South African operators were more profitable than those in all but three countries — Kenya, Morocco and the UAE — in the 2015 and 2014 financial years.

And the difference was notable. Where South African service providers outstripped their competitors, it was generally by several multiples, in some cases up to 20 times more.

The price of data has come under sharp scrutiny in recent weeks, with radio personality Thabo Molefe leading the #DataMustFall campaign on social media, calling for consumers to boycott service providers who don’t drop their prices within 30 days.

The case for lower data rates was heard in Parliament on Wednesday. Molefe described the data prices as “daylight robbery”. He said they needed to be halved to be affordable.

A recently released ICT Africa report says lower-income South Africans are spending 20% of their income on one gigabyte of data — four times that recommended by the International Telecommunication Union.

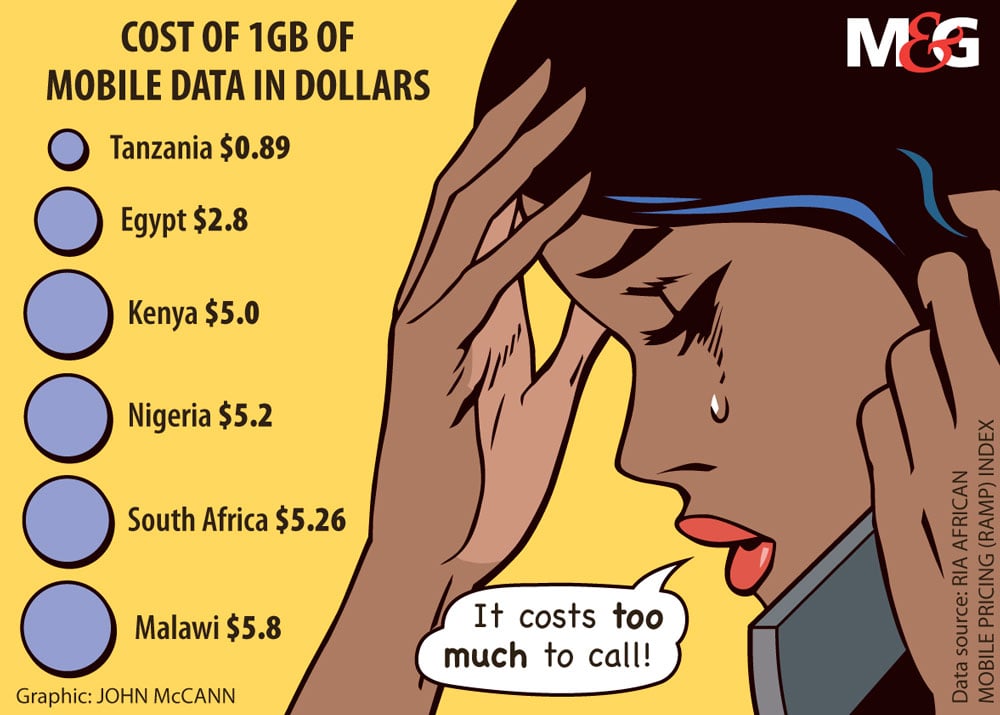

“Regionally, data prices remain expensive,” said the ICT Africa report. “South Africa’s cheapest 1 gig data places it at 16th of out 47 African countries assessed. Tanzania has the cheapest one gig for $0.89 in comparison to South Africa priced at $5.26. In comparison to other large markets, Egypt, Kenya and Nigeria have lower data prices than South Africa.”

The Mail & Guardian went through the published financial results of each company for the past two years and compared their revenue with their net profit or income after tax to derive a profitability percentage in each case.

Generally speaking, in countries where customers are charged lower rates for data, the profitability of the service operators was correspondingly lower. In countries where data costs were higher, operators reported bigger profits.

Out of the companies researched by the M&G, Vodacom and MTN were ranked, depending on the year, in one of the top three positions in terms of profit.

The majority of their competitors, selected from a group of large telecoms providers in emerging markets, reported profit margins ranging from 0.09% to 5.6%.

Indian-based telecoms giant Airtel, the largest service provider in that country, had a profit margin of 3.2% in 2014. This increased to 5.6% last year. Idea Cellular, the third largest in India, reported a profit margin of 0.33% last year, which was up from the slight profit it made the year before.

America Movil, a large player in Mexico and Brazil, recorded a 3.9% profit last year and a 5.2% profit the year before.

By comparison, MTN had a group profit of 13.7% last year, which was a notably bad year as a result of a large Nigerian fine. In 2014, a more typical year for the company, it reported a profit margin of 25.7%. This was the biggest profit calculated out of all 10 companies over both years.

Vodacom, which complained of flagging performance in 2015, still managed to garner 16.18% group after-tax profit as a percentage of revenue, and enjoyed 18.05% margin the year before.

Operators in three other countries reported similar profits to the South African giants: Etisalat, a multinational that derives its income mainly from the UAE, but also has operations in several African countries such as Egypt, Morocco and Nigeria, had profits of 18.8% and 19.9%; Maroc Telecom, which, with more than 11 000 employees in Morocco appears to enjoy a stronghold in the market and recorded profits of more than 22% in both years; and two in Kenya, which both had profits of about 18%.

There is a strong relationship between the prices charged in the relevant countries for data and the profitability of the companies.

For example, in India, where service providers’ profits are low, the average price for one gigabyte of data is R11. South Africans pay R149 for the same amount and service providers are making commensurate profits.

In Egypt, consumers pay half the amount they do in South Africa. This correlates with the low profits recorded by Egyptian service provider Orange Egypt, which made a profit of 0.09% last year and a loss the year before.

In contrast, Morocco was similarly priced to South Africa, and Kenya was relatively close, so their service providers’ profits of 18% to 22% should not elicit great surprise.

But Vodacom has refuted the validity of the findings.

“The picture presented is not representative of the actual position,” Byron Kennedy, Vodacom’s spokesperson, said.

“Looking at data, our prices have been coming down at a rate of about 20% over the past three years. Furthermore, since data was first offered by Vodacom in 2001, prices have fallen by around 95% and in instances Vodacom offers zero-rated content [free of charge] to select content services.

“It is also important to note that in 2015 alone the average price our customers paid for data fell by 13.6%. In the past two years, we have migrated many of our contract customers on to better value price plans where, for example, our out-of-bundle rates have dropped by up to 50%,” Kennedy said.

But the results of this exercise suggest a fairly simple narrative: when the customer pays more, the company’s coffers benefit accordingly.

Kerwin Lebone, the head of the centre for risk analysis at the South African Institute of Race Relations, said: “Out of the five major cellular networks [including Cell C, Telkom Mobile and Virgin Mobile], Vodacom and MTN own 71% of the market share of subscribers with a total subscriber base of 62.8-million between them. With such a dominant presence and lack of competition, they have the allowance of setting their own prices for data.”

He said the regulatory environment is largely to blame for it. New players wanting to make use of wireless broadband in South Africa are required to put up a huge sum of money before they will even be considered by the regulator.

“The reserve price for the ITA [invitation to apply for high-demand spectrum for the expansion of wireless broadband services], which is expected to commence in January 2017, is R3-billion,” Lebone said.

“The amount automatically excludes small network providers who might, through innovation, provide much cheaper and quality services to consumers.

“In this anti-competitive business environment, it is no surprise that the established networks are able to earn huge profits.”

MTN had not responded to a request for comment by the time of publication.