Fela Gucci and Desire Marea may be the monikers of gender-nonconforming performance artists Thato Ramaisa and Buyani Duma, but the characters were born in 1991, the same year that birthed the dark-brown bodies that unsettle ignorances and tickle fancies everywhere they go as FAKA.

It’s almost been a year since FAKA furnished the internet with From a Distance, a four-minute video in which the duo take Bette Midler’s words to the top of the Melville Koppies where God watched them dance to their own song, bare-chested and wearing copper-coloured Afro wigs.

Although FAKA was only established last year with the introduction of the brashtag #siyakaka, in the past 12 months they have already performed a much-talked-about scene at Stevenson Gallery’s Sex exhibition, recorded Isifundo Sokuqala, the follow-up song and video to From a Distance, and performed at the Berlin Biennale.

The collective has also appeared in the New York Times, collaborated on a futuristic shoot with Adidas and disrupted what they have termed Niveaness: “The ever-polished, superficial persona of the cisgender metrosexual, who wears head-to-toe Markhams. He stays in Sandton or in a Marshalltown bachelor pad and carries a lot … The fact that you are ‘Nivea’ over, like, ‘Vaseline’ – it is a form of self-protection.”

That’s not bad for Duma, a copywriter at the Joe Public advertising agency who hails from KwaZulu-Natal, and Katlehong-born Ramaisa, who is about to start a new job managing an artist residency space.

As they prepare to release their first EP Bottoms Revenge in October, during a Sunday-afternoon Google hangout, the two discussed being cultural capital in an irrationally capitalist society, using public transport in Jo’burg, mental health and dealing with the gaze of two-faced photographers.

Can you each describe the room you are sitting in?

Desire Marea: I’m in my living room/kitchen. Poor lighting, so I can’t selfie. One couch, a few golden glass tables, and a mandatory pot plant for the Instagram ambiance (lol).

Fela Gucci: I’m sitting at the dining table. There are black chairs, the walls are red and there is an ironing board I keep noticing.

Do you each live alone?

Desire: Yes, I live alone in the ’hood section of Marshalltown.

Fela: I live with my lover in Kensington.

Do you drive or use public transport? I’m trying to imagine what your daily commutes are like in Johannesburg taxis wearing the clothing you wear. Is it ever, always or sometimes a drama?

Desire: We use public transport.

Fela: I have never had a physically violent experience in taxis except having people look at me like I’m strange. I immediately feel unsafe for being visible, especially when there are men in the taxi.

Desire: Sometimes it is a drama but it is a subtle drama, mostly: a change of mood as soon as you walk in. In the morning most people are minding their own bad moods. The people who cause drama are usually people in the neighbouring taxi. When both taxis stop at a robot, a passenger from the other taxi may start shit and comment on your appearance. I guess the distance gives them that power. Sometimes the driver of that other taxi would ask the driver of the taxi I am in what’s going on, and my driver would be embarrassed like his squad saw him at the mall with his gay cousin type of vibe. I have recently started using the Gautrain for safety, peace and convenience.

Do you feel safe in public spaces? Or do you feel powerful in your disrupting of public spaces by fucking with the fragility of masculinity and gender performance?

Fela: I don’t feel safe in public spaces, especially as someone who has clinical anxiety. My being visible, coupled with the anxiety, often makes me feel unsafe. I realise that I disrupt the idea of masculinity that most men uphold and that that puts me at a risk of being attacked.

Desire: Mostly power. It’s unsafe because the power might expose the fragility in men and when they confront that so suddenly, they might retaliate with an attack that reinforces their ideas.

So would you say that Buyani and Thato always have to take a backseat to Desire Marea and Fela Gucci when you’re out, or are you in essence performing your actual selves and there’s no separation between the four?

Desire: For me, the lines are very blurred lately. The aim was always for the performance to become our lives, but it is a scary commitment and a huge sacrifice.

Gosh, I can’t imagine the levels of vulnerability that you have in storage but that’s the source of the power, in being vulnerable.

Desire: Yes, that is where the power is. I don’t know how to explain it; it’s like we transcend it. We are always unsafe, but vulnerability and the power that it exposes us to helps us transcend the condition of unsafety.

How do you manage the relationship between your virtual visibility on social media, the reproduction of those images and your visibility on land?

Fela: Personally, there’s no separation. It feels really organic to exist as Fela Gucci. The only time that it feels like I need to switch off from existing as Fela Gucci to Thato is when I’m forced to be in a space with extended family who make it difficult for me to exist as myself. They hold a lot of prejudice and expect me to perform masculinity.

Desire: The virtual visibility is performative and you could say that it is an idealistic and utopian representation of our lives and what we want our existence to mean. Our existence is that in many ways, but there are obviously complexities. The pressure does come from that, but that’s what we wanted. Lately, we can’t be anywhere as anybody other than Fela Gucci and Desire.

I can imagine. It’s like you’re a living artwork. Not to objectify you or anything, but that’s what makes it so powerful. Ways of dress and adornment are the fundamental street and public art.

Desire: Yes, that is what it is becoming but we have accepted it as a calling, and the nature of the work we have to do requires us to be living artworks.

Fela: It feels safer for me to be visible online. I have found an online community of people who liberate me and make it feel safe for me to be visible as myself. I realise that, outside of that community, people may not have an understanding of or be receptive to my identity as a nongender-conforming person. It’s very difficult for me to not exist as myself, so as much as I hold anxieties of being visible, I’m not willing to compromise my power.

Do you ever feel alone? Or do you feel like you’re connected to another force that’s guiding your journey and lighting your way?

Desire: Our ancestors guide us through it all.

Fela, would you say that family is essentially the most oppressive institution? Because all of our social pathologies and prejudices play themselves out there. And uncles and aunts can get violently emotional about respectability. Like the taxi drivers can’t beat you, but your uncle “can”.

Fela: My personal experience has been quite violent. Nothing physical, but the violence of policing my expression. I have had an uncle tell me with spite that I dress gay, which has made it very difficult for me to speak openly about my identity with my family. So, yes, I think family can be a really oppressive institution.

How has capitalism responded to you and your art?

Desire: Capitalism gives us access to all the artefacts that can have a different meaning when subverted. Also, when you are at the forefront of a cultural phenomenon in a time when culture is gaining a lot of economic power, you will find people trying to commodify you. It is weird for us because the thing they would commodify is the very idea of our bodies, our identities basically.

The relationship between virtually visible, self-made internet stars and capitalism is scary. As a blogger or artist, one has to survive but it’s so scary how “influencers” are being “influenced” by brands to push their products. Have you been approached by brands yet (I just saw the series with Adidas that you did) and how have you handled that relationship?

Desire: You know, it is an inescapable reality. We grew up in a very consumerist black society and in many cases the choices concerning brands were very irrational, in a sense that we believed that the brands did something to us that made us “better” or “okay” or “less black and poor”. I think that was a reality a lot of black youth were trying to escape: the fact of poverty. We believed brands had the power to change that narrative.

We find it interesting now, to see brands scrambling for relevant black artists to change the narratives of the cultural bankruptcy of their brands. The Adidas campaign for us was more a story of representation and in a way we had to have faith that that story would be more potent.

The inescapability of being in a hyper-consumerist society keeps me up at night and makes me wonder about the future and whether any of us knows what the fuck we are doing. How do you take care of your mental health?

Fela: I meditate every morning. I speak good things to the universe and myself. Last year I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder after experiencing two psychotic episodes. It was a really scary time in my life but I sought help and now I’m seeing a therapist every week and taking medication, which is honestly really helpful for now.

Desire: The idea of being paid a lot for being who you are because you do it well is nice. It’s a new craft and I actually respect it. It fascinates me but I feel like choosing your own narrative is always key when aligning yourself with brands, because most of them think they can superimpose you against their existing brand world and that’s just awkward, to be honest.

I actually see potential for new narratives to be written using the meanings of brands strategically or subversively. I don’t think anybody has cared to do that.

I feel like I could talk to you all day. What years were you born in as Buyani and Thato and when did Desire and Fela Gucci come into the world?

Fela: My birthdate is February 22. I was at a party, dancing to Fela Kuti, when I suddenly thought it would be cool to call myself Fela Gucci. I believe that Fela Gucci was born when Thato was born because so much of what Fela Gucci expresses is rooted in childhood memory and my experience of growing up with the trauma of losing both parents and coming into myself, trying to create a new narrative for myself through Fela Gucci. I’m able to reimagine myself, which has been really empowering.

Desire: Most of my names came through Thato, actually. Thato called me Bob Maria after I wrote a cheesy Facebook status that contained Bob Marley lyrics. I loved how the name shattered the gender of a revolutionary male artist, and I wanted to be a revolutionary gender-nonbinary artist, so I kept it for a while.

Desire came by accident when I was trying to call myself Des’ree after the You Gotta Be singer. Then Thato was like, Desire babes, and I was, like, I love that name. It is everything that I am.

I want to address the issue of the white gaze but I think I have taken up enough of your time this afternoon. Can I email you?

Desire: Yes, that’s something we are open to. We have stuff to say.

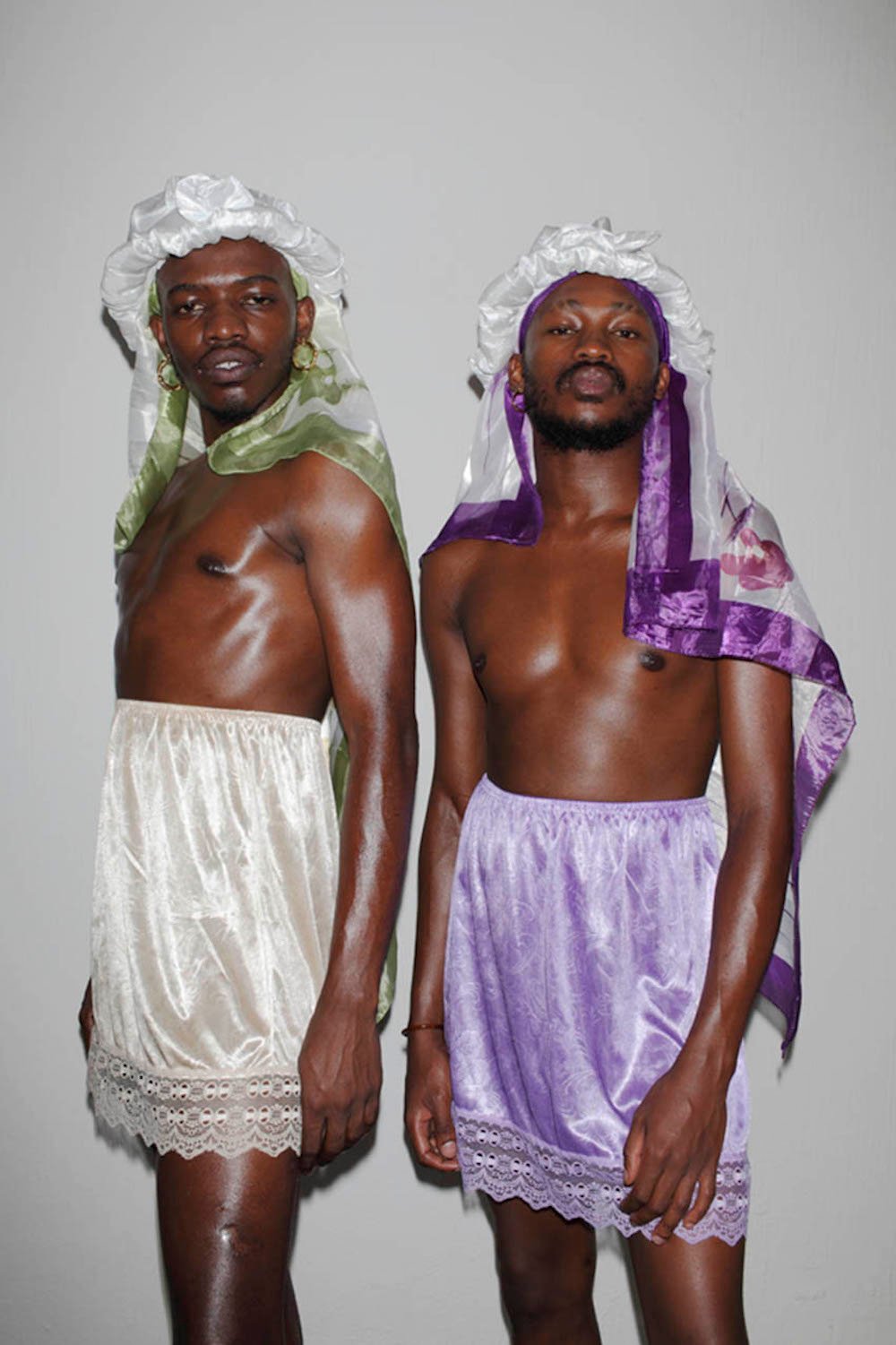

FAKA. (Nick Widmer)

Later that night by email:

From: Milisuthando Bongela

Date: Sun, Sep 25, 2016 at 7:26 PM

Subject: The rest of the questions

To: santu ramaisa, Buyani Duma

A few months ago, I got a text message from an artist. In it, she was expressing anger about white photographers’ gaze on black cultural producers here, speaking to the historical narrative of the colonial gaze. She was upset about the fact that talented white photographers are becoming the authority on black culture when they travel overseas these days. I remember you two posting something similar on Facebook a few months ago. What is your experience of this kind of thing in your own work?

From: santu ramaisa

Date: Mon, Sep 26, 2016 at 3:50 PM

Subject: Re: The rest of the questions

To: Milisuthando Bongela

Cc: Buyani Duma

Yes, we did post something about this in a response to Phumlani’s [Pikoli] status about the matter and it was based on the exploitative behaviour from somebody we trusted with our bodies, who happened to be a white female photographer. This is somebody we had been collaborating with for over six months, creating iconic visuals together under the guise that we were equal collaborators. Throughout this time her exploitative behaviour surfaced more and more, revealing her otherwise subliminal colonial understanding of photography and documentation as a whole. A clear account of this is when we heard, from a colleague, that an image we had all worked on was being exhibited under her name alone in an exhibition we knew nothing about. It was further exacerbated when we found out through a widely shared Facebook link that our bodies were being shipped to New York without our permission, to be sold for her benefit. This felt like a modern iteration of a very dark past, with a new seemingly “progressive” façade because of the themes that were explored in the images and neoliberal faith in things that have never and will never exist – like a sincere white author of black narratives.

That faith is the illusion under which the West has been operating for years and the fact that they were all so willing to accept her as the authority of subjects she knows nothing about still tells you that white people prefer to see us through their eyes only. The minute they see a black person curating their own representation, it doesn’t feel authentic or “African” enough for them and they dismiss it because authority has never been an “African” thing, right?

How do you work within this complex framework where talent and identity intersect?

We are still navigating a way that actually works for us, because it is very complex in the world we live in, and colonial modes of operation still dominate the creative industry. We have to change the way we look at photography/art in a way that will make sure that the power is relocated back to the (black, queer) subjects who exist.

Is it avoidable?

Sadly, a black artist doesn’t always have the privilege to say no.

Does it matter what race or gender the person behind the camera is, since your work is about disrupting identity norms?

It matters only because of how the world still views photography and who they choose to give more power to. If they accepted that we, as black queer artists, are the source of the power in every picture, and if we were paid enough, then it wouldn’t matter who is behind the camera because, in the context of performative imagery, it isn’t about them anyway.

In 100 years’ time, do you think race and gender and sexuality will matter as much as they do now?

We certainly hope not. But they have to matter a lot more in order for them to truthfully not matter.

Do you want to be cash-money rich?

Yass.

What, in your opinion, is the currency of the future?

We don’t know what it is exactly but we know it is in Africa.

FAKA will be performing new and old material at the Unsound Festival in Kraków, Poland, from October 16 to 23. Their EP Bottoms Revenge is due for release before they leave. Keep up with them on Instagram – @desiremarea and @felagucci – and via their blog, faka-blog.tumblr.com