Hair extension are a popular salon treatment. (Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

Paulina*, a middle-aged woman, drops two Castle Lites into the rubbish bin. With a stiff broom she sweeps up the sweet wrappers, plastic containers and loose ends of nylon hair. Soft clippings evade her reach; they skim across the floor and settle underneath the swivel chairs. No matter.

The beauty salon is small, a narrow wedge of floor space not wider than the burglar bars that protect the front entrance. It is easy to clean and keep tidy. Paulina prefers the small space for other reasons too. Her kanga, a Kiswahili cloth wrapped around her waist, says it all: Riziki mwanzo wa chuki – income is a source of hatred. Or, as Paulina gamely puts it, "I get money, now I get trouble."

This is an edited extract from "I get money, now I get trouble: Tanzanian women in Durban", part of a collection of stories from Writing Invisi-bility, a collaboration between the Mail & Guardian and the African Centre for Migration and Society and funded by the Max Planck Institute. Download a copy of the book here

Proverbs – patterned on dresses, adorning the edges of skirts, spoken in conversations and explicated in interviews – help frame my interactions with Tanzanian women in Durban's city centre.

To the mixed delight and boredom of Paulina, I recite these sayings over and over, attempting to gain an insider's knowledge from an outsider's perspective. When spoken aloud, the proverbs bring forth smiles, for they convey the commonalities of social life. Occasionally they bring unease. In the fold of a kanga, a flash of material displays a message that cautions not all is what it seems.

Here, backs and shoulders press up against the walls, the chairs too few to accommodate so many. Generous helpings of advice match generous helpings of food – roasted meat and pap, purchased from the butchery next door. Diced chillies, an obligatory garnish in Durban, rim the edges of chipped plates. If the money is right, beer and cider make an appearance too.

Amid the relaxing, washing, blow-drying, combing, plaiting, twisting and braiding of hair, Paulina eats and drinks from an elevated position – either sitting on the edge of the counter that runs the length of the salon or standing in her platform shoes, a professional necessity due to her short stature.

A woman runs into the salon and heads to the back. She begs Paulina to push the sink to the side, exposing a drainage hole. She lowers herself down in relief, her kanga collected around her legs. More women follow, taking turns to stand in front of each other, blocking the view of pedestrians looking in.

Tuko pamoja

(We're together). Tina, a recent arrival to South Africa, explains the concept to me more fully. Although a Tanzanian citizen, Tina has spent most of her adult life in Kenya.

When I ask Tina if tuko pamoja exists in Kenya, she says no. I am surprised, for Kenyans speak Kiswahili.

Tina elaborates. "Like they have in South Africa, there are Zulus, Xhosas and Sothos. In Kenya, it's the same thing. Zulu-Zulus, Xhosa-Xhosas, Sotho-Sothos. They don't have tuko pamoja. In Tanzania it's not like this. They treat you as one."

Tanzania: a country that boasts more than a hundred different ethno-linguistic groups, a country where Tina does not notice social divisions. This sense of cohesiveness may be attributed to Tanzania's first president, Julius Nyerere, who in his vision of African socialism and unity strove to minimise differences that might engender inequality, like ethnic privilege, as well as class and religious polarisations.

Yet, although tuko pamoja has positive associations in Tanzania, the same does not hold true in South Africa. To migrate abroad often means to seek out personal advancement, a position at odds with the commonalities of tuko pamoja.

Photo: Oupa Nkosi

Photo: Oupa Nkosi

Selina, who has resided in South Africa for nearly a year, offers this explanation. "There's no getting together when it comes to Tanzanian people living in South Africa. Many don't want you to go further. They want you to stay right there."

At which Selina lowers her hand to the floor and emphatically states: "All of you being equal."

In this case, tuko pamoja represents the lowest common denominator – of being poor but evenly matched with everyone else also struggling to make it in South Africa.

Haba na haba hujaza kibaba

(Little by little you will increase your savings). To accrue money in South Africa, Tanzanian women often start with small jobs. They scrub floors and toilets, sell pastries from buckets, train as hairdressers, manicurists and waitresses, for little or no pay.

They pool their resources to make ends meet, sharing flats with relatives, boyfriends and strangers who they encounter during their travels.

"Two cups, two plates, two spoons, and one bed" is how Paulina describes her living situation during her first few years in Durban. The two, two, two, one count indicates Paulina's meagre possessions as well as her marital status.

Recently divorced, Paulina left Tanzania in 1998 to start afresh in South Africa. Along the way she met her second husband, a Mozambican sailor. They chose Durban, a seaport city that offered the possibility of employment and the chance of finding a secure and affordable flat.

Between 1998 and 2000, Paulina and her husband scrimped and saved to improve their lives as well as the lives of the three young children Paulina left behind in Tanzania. Prudent with their money, they survived by buying food in bulk and renting cheap rooms in the Point area.

Not only thrifty, Paulina was also diligent, learning English and isiZulu bit by bit. It helped her secure work in salons, the first one run by a Nigerian and the second by a Ghanaian. In both cases, the men cheated Paulina out of her wages.

In retaliation, Paulina wrote out slips of paper undercutting the prices of her bosses. With these slips of paper, she established a contact base for customers to come to her flat.

The supervisor eventually noticed Paulina's activities, brought to his attention by complaining tenants, and in a gesture of kindness and business savvy offered her a commercial space on the street below. Paulina agreed to the rental of R450 a month, installed a sink and mirror, and thus began her enterprise of turning small things into big things.

Riziki mwanzo wa chuki

(Income is a source of hatred). Revival, a woman of 42, contemplates the proverb written on Paulina's kanga. In many respects, Revival's circumstances parallel those of Paulina. She, too, is a hairdresser and owns a beauty salon in the Point area. Also, like Paulina, Revival arrived in Durban in the late 1990s, leaving behind in Tanzania young children and an estranged husband.

Similarly, she opened a beauty salon in her flat, which she expanded into a small shop, another bigger shop, and now what she calls her "two-in-one", an establishment that accommodates hairdressers and manicurists and another small business in the back.

Despite her success, Revival harbours bitterness about her relocation to South Africa, saying, if she had known of the difficulties beforehand, she would have stayed in Tanzania.

Unlike Paulina, Revival never brought her children to live with her or even to visit South Africa. She supported them and her mother from afar. She explains: "It's like I'm on the fire. I can't call someone into the fire."

Revival's desire to stay in Tanzania is not atypical of her compatriots.

Historically, too, the presence of Tanzanians in South Africa has been small compared to other migrant groups from the Southern African Development Community. This, in part, can be traced to the frontline politics.

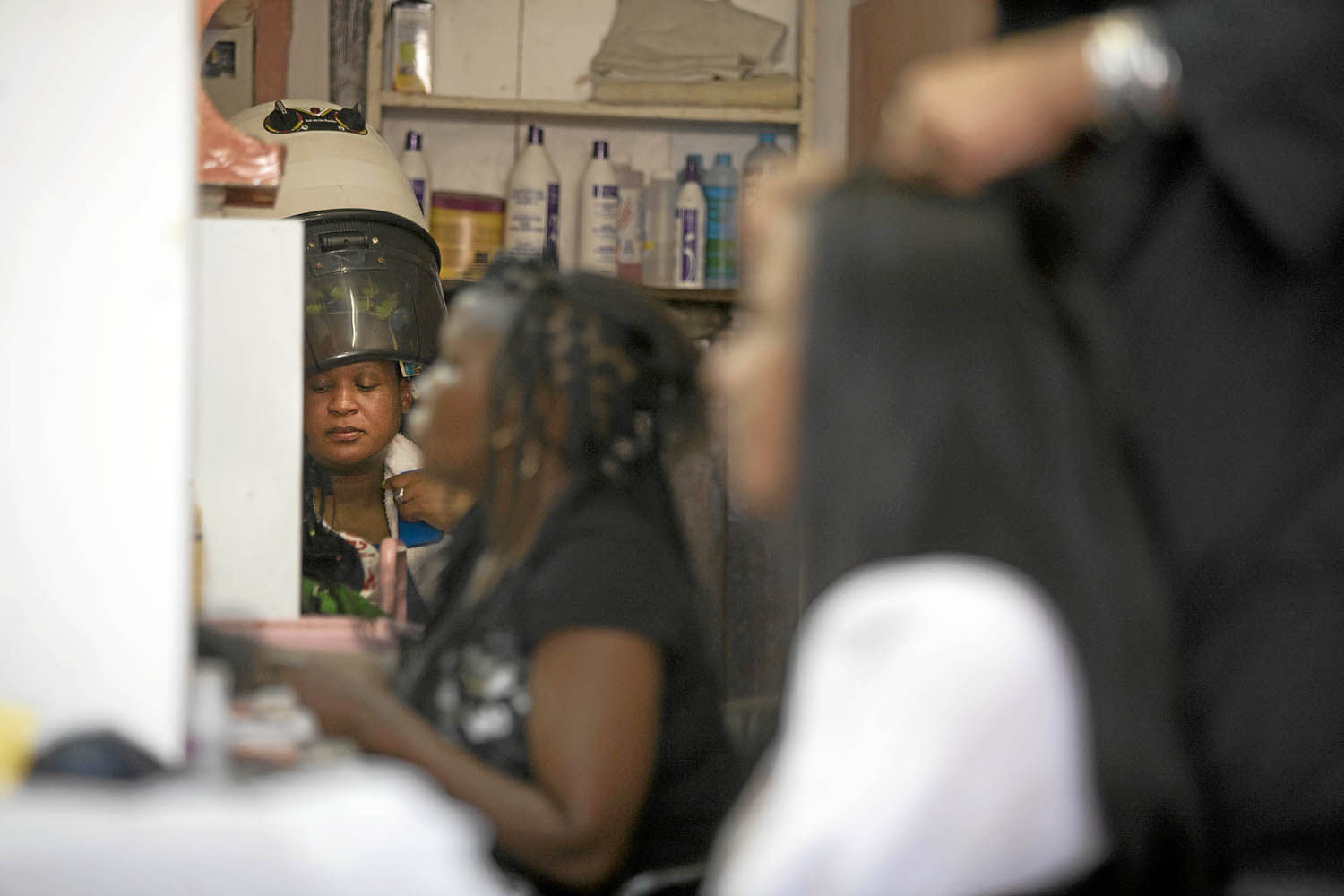

Simple beginnings: A customer gets a dry perm. (Oupa Nkosi)

Simple beginnings: A customer gets a dry perm. (Oupa Nkosi)

In 1962, Nyerere withdrew Tanzanians from South Africa, a move that conveyed his condemnation of apartheid. Labour statistics from the gold-mining industry provide the most vivid picture of this repatriation, as the number of Tanzanian miners dropped from more than 14 000 in 1960 to zero in 1970. The South African census from 1985 corroborates this small figure – it reported 887 Tanzanians living in the country.

On the flip side, the year 1985 also signalled the departure of Nyerere from political office. At the time, the Tanzanian government faced massive economic stagnation, which prompted Nyerere's successor to adopt the structural adjustment programmes of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

This, in turn, contributed to a growing gap between the rich and poor. The devaluation of the shilling pushed up the prices of commodity goods, the reduction in government spending cut social welfare services and the privatisation of parastatals led to higher levels of unemployment – all of which hit ordinary Tanzanians the hardest.

They increasingly began to rely on the informal sector, particularly in urbanised areas, to supplement their daily incomes.

In his study of the informal sector during the 1980s and 1990s, anthropologist Joe Lugalla differentiates the economic approaches of two demographic groups in Dar es Salaam: the first consisted of the urban poor, who relied on the informal sector to meet their basic needs, while the second consisted of the middle and upper classes, who capitalised on the informal sector for their business dealings.

Lugalla's discussion of beauty salons, which proliferated in Dar es Salaam soon after the liberalisation of the economy, bears particular relevance to the experiences of Paulina and Revival.

As Lugalla notes, the purchasing of foreign beauty products, associated with Westernised values of "modernity", set up a socioeconomic distinction in which wealthier Tanzanians had access to salons, not only as clients but also as businesswomen. Because the salons were part of the informal sector and thus considered "illegal", it required women of some education, skill and personal connection to acquire the beauty products as well as the know-how to establish a business out of sight of government officials. Bribes, of course, helped officials look the other way.

When asked why they sold their beauty salons in Tanzania to come to South Africa in the 1990s, both Paulina and Revival explain it was a difficult profession. Business licences presented one problem but so did the irregular supply of clients. As Revival puts it: "See, now to open a business in Tanzania, it's not like before. Now they say it's better because people understand things. You can get customers. Before nobody had nice things."

Revival's statement draws attention to the pervasive influences of capitalism and its emphasis on commodity goods or "nice things", which increasingly have directed women's disposable incomes to beauty salons.

The South African economy presented these opportunities well before Tanzania although, as Revival notes, only now is she reaping the benefits of her hard work. "Maybe I'm getting," she explains, "but I'm getting at last."

Furthermore, this getting comes at a cost – a cost that directly affects Revival's personal relationships.

"Your mother likes to talk," Revival addresses her comment to Lulu, who is Paulina's eldest daughter. Early on in my research, Paulina dispatched Lulu to my services as a Kiswahili translator.

"Eh-heh," Lulu laughs in reply. "My mammy is stupid. This one," indicating Revival, "is a quiet woman."

"You know the problem," Revival says. "There are a lot of people who need to make friends. They can't be alone. If you like friends, you'll have them but you'll get their problems too. Me, I'm not used to having friends. My heart is not very public."

(Photo: Oupa Nkosi)

(Photo: Oupa Nkosi)

But her solitude and quiet demeanour do not evade unwanted attention altogether. At the time of our interview, several Maasai men were working in Revival's salon as hairdressers. Their skill at quickly twisting hair gained traction with women who did not want to wait long for their hair to be styled.

Although her competitors admired her ingenuity, they also put out a rumour that she imported the men from Tanzania, paying for their transport in exchange for work.

The rumour, although false, still managed to present an underside to Revival's success – one that, with insinuations of indentured servitude, countered her carefully constructed persona of respectability.

She notes her economic visibility, or "luck", makes her susceptible to outside resentment and suspicion: "You know riziki is like luck. A big salon, like this, it's the luck. But also people can hurt me. They can hurt me a lot for the luck I have got."

Referring to Paulina's kanga, Revival elaborates, "Because this riziki is luck and chuki is hate".

I climb the six flights to Paulina's flat. The lift does not work. Just outside her door, children eagerly wait for the birthday party to begin.

Paulina greets me and pushes an invoice in my hand. "What does it mean?" she asks. I look at it: a municipal statement.

"They're adding meters. Soon they'll be charging for water."

Paulina wrinkles her nose and takes the invoice back. She ushers me into the living room where more children sit, closely pressed together, on the floor. They are partitioned off from the bedroom by a hanging curtain. Women wander in and out of the kitchen, helping with the cooking – frying chicken and chips, mixing salads and spicing dishes of pilau.

"Never again!" Paulina announces, three hours into the party. Red-faced, she rearranges the furniture, once more, trying to create space for the arriving guests. All of them are given plates of food.

The cake is set out, its size approximating that of Paulina's young son. A scanned photograph of him peers up from the top layer, as he is the reason for the party. After the first cut, the cake disappears quickly. One child settles for the frosting clinging to the inside of the discarded box.

Jungu kuu alikosi ukoko. A big pot is not without some (leftover) crust. It is an image of abundance and communality as well as scarcity and inequality.

* Names have been changed in this article to protect the identities of the people involved