Johannesburg has become the fastest location in the country to register property and get an electricity connection, followed by Cape Town and eThekwini (Bloomberg)

Mega-bank Absa could be forced to pay R2.25‑billion to the fiscus for an unlawful apartheid-era bank bailout if a preliminary report by the public protector remains unchanged.

In Busisiwe Mkhwebane’s suggested remedial action she also proposes that the president should consider a commission of inquiry into apartheid-era looting of the state.

The damning preliminary report, which the Mail & Guardian has seen, has been sent to Absa, the South African Reserve Bank, the treasury and the presidency, as the head of government, which is implicated in the report.

Mkhwebane has provisionally found that the government breached the Constitution and the Public Finance Management Act.

However, Mkhwebane told the M&G that the report was preliminary and that she was awaiting feedback from the implicated parties – “information which might change the final report drastically”.

Absa, describing the preliminary report as containing “several factual and legal inaccuracies”, said it perpetuated an incorrect view that Absa benefited from the bank bailout in question. In a statement responding to detailed questions, Absa said it was “regrettable” that the interim report had been leaked.

View Absa’s full statement HERE.

The public protector has given implicated parties until Monday to make submissions as to why her report should not change but some have requested an extension, and now have until February 28 to respond.

The report has its roots in a 1997 investigation by Ciex, a covert United Kingdom-based asset recovery agency headed by former UK intelligence official Michael Oatley. Oatley allegedly approached the South African government to investigate and recover public funds and assets misappropriated during the apartheid era.

The government, through the South African Secret Service represented at the time by Billy Masetlha, contracted Ciex to investigate the allegations of large-scale looting of the state under the apartheid government.

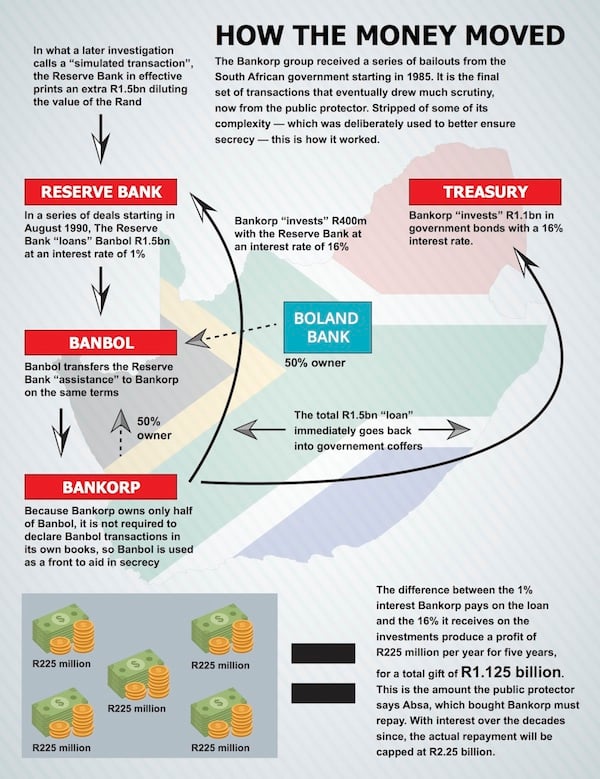

The Ciex report, called Project Spear, looked into how R1.5‑billion was offered to the Bankorp group of banks disguised as a distressed bank “lifeboat”. It also investigated R100‑million given to Nedbank and several billions of rands siphoned offshore illicitly.

From 1985 to 1992, the apartheid government, through the Reserve Bank, provided Bankorp with a series of bailouts to offset bad loans that threatened the bank’s survival. One of these was a payment of R225‑million a year for five years.

It was implemented in a very complex series of transactions, described as “simulated transactions”.

According to one investigation, these were deliberately engineered for secrecy, in one case using what amounted to a front company.

In 1999, Ciex suggested that the Reserve Bank should recover the billions from Bankorp, which had been taken over by Absa.

But according to the public protector’s preliminary report, the government failed to implement Project Spear, even though it had paid Ciex “for a period of six months amounting to 600 000 pounds, equivalent of R10 556 972.40”.

Mkhwebane’s report is in places ambiguous on what the governments duty was in dealing with the findings of the Project Spear investigation. It states that having paid for the Ciex probe, the government had a duty to “process” it – formally consider it and make a decision. Elsewhere she talks of a duty to “implement” the report.

The public protector’s report also describes how different investigations into the same matter came to different conclusions.

In 1999, the then head of the Special Investigating Unit, Judge Willem Heath, conducted a similar probe into Bankorp’s so-called lifeboat. Heath found the bailout was unlawful but advised against instituting a claim, saying it would lead to a run on the banks and would destabilise the sector.

Then, in 2000, former Reserve Bank governor Tito Mboweni commissioned another investigation. A panel headed by Judge Dennis Davis delivered a 150-page report, agreeing that the bailout was unlawful. However, Davis’s panel said that the Reserve Bank’s claim would lie against Sanlam, Bankorp’s former shareholder, and not Absa.

Absa said it “emphatically agreed” with the Davis panel’s findings. The bank said it had invited the public protector to inspect confidential documents related to the due diligence review it conducted before buying Bankorp, but that this invitation had never been taken up by the public protector.

According to Absa, the documents would show that it had paid “fair value” for Bankorp.

“All the obligations pertaining to the South African Reserve Bank’s assistance were discharged in full by October 1995,” it said.

Mkhwebane would not comment further, saying the leak of provisional reports undermined the investigative process.

In her preliminary report, Mkhwebane said neither Heath nor Davis was told of the Ciex findings, especially the suggestion that if Absa were to “stagger” repayments by paying in tranches, it would not affect the economy.

“[T]he [Reserve Bank] commissioned Judge Dennis Davis in 2000 to look into the same matter but not disclosing the Ciex preliminary findings in the Davis commission, which the then Reserve Bank governors Tito Mboweni and Gill Marcus were aware of,” reads the report.

Both Mboweni and Marcus independently said they could not comment on a report they had not seen, and referred questions to the Reserve Bank. Jabulani Sikhakhane, head of Reserve Bank communications, said the bank had received the provisional report, was “studying” it and would “respond to the public protector within the timeframe set by that office”.

In building her report, Mkhwebane refers to evidence provided by the former Reserve Bank governor, Dr Chris Stals, who placed responsibility at Absa’s door for repaying the Bankorp bailout.

Stals’s evidence suggested that Absa entered into a loan agreement with the Reserve Bank on April 1 1992 and that the agreement included repayments with interest. Although the capital amount was repaid, the interest was not, the public protector’s preliminary report said.

Stals also told the M&G that he could not comment on a report he had not seen.

The public protector said she also interviewed former president Thabo Mbeki, who said that the decision to recover the money would not have been taken by his office and would have rested with the minister of finance at the time (then Trevor Manuel) and the Reserve Bank.

“The president contended that part of the reasons the money was never recovered had to do with the economy which had to be protected,” reads the report.

“His view was corroborated by that of the former minister of finance, Mr Trevor Manuel, who stated that his primary role was to protect the interest of the economy against any potential risk, taking into consideration that we were in the process of rebuilding the economy.”

Mbeki could not immediately be reached but Manuel said he could not comment as he “would not like to prejudice a necessary discussion about this matter”.

Mkhwebane has provisionally found that “the conduct or failure of the presidency, national treasury and [Reserve Bank] to process the Ciex report … constitutes improper conduct, as envisaged in the Constitution, and maladministration”.

Saying Absa “unduly benefited”, Mkhwebane added that the decision not to recover the money “had a serious prejudice on the people of South Africa, particularly the poor who would have benefited … through social development programmes”. The public had lost out to a “few individuals who are shareholders of Absa”, she said in the leaked preliminary report.

“Government and [the Reserve Bank] had an opportunity to recover [the money] but decided otherwise.”

Just keep swimming: A timeline of lifeboat reports

Public Protector Busisiwe Mkhwebane. (Moeletsi Mabe/Sunday Times/Gallo)

The secret, oddly structured bailout that was provided to Bankorp in the 1990s, and eventually inherited by Absa, has been the subject of several investigations. The provisional report by the public protector is the first to recommend that money should be recovered through legal action by the state. This is how the different reports stack up.

Provisional public protector’s report,

December 2016

By public protector Busisiwe Mkhwebane, assisted by investigator Tshiwalule Livhuwani. Instituted by Thuli Madonsela, who used her discretion under the Public Protector Act to launch an investigation based on a 2010 complaint by Paul Hoffman of nongovernmental organisation Accountability Now.

Finding: Absa “unduly benefited” to the tune of R1.25‑billion plus interest over two decades. The government could have recovered up to R2.25‑billion from Absa, and it and the Reserve Bank failed the nation by not doing so.

The treasury and the Reserve Bank must now institute legal action to recover that money and ensure that “new, stringent and appropriate policies and regulations” are put in place within 90 days “to prevent this anomaly in providing loans/lifeboats to banks in the future”. The president should consider setting up a commission of inquiry to see whether other apartheid-era loans are due from other institutions.

Report of the governor’s panel of experts, known as the Davis Panel,

February 2002

By a group headed by Judge Dennis Davis and including the heads of three chartered accounting firms, a British professor, a Swedish central banker and an International Monetary Fund adviser. Panel appointed in 2000 by Reserve Bank governor Tito Mboweni.

Finding: Bailing out Bankorp was justified in the interests of protecting the stability of the banking system, but “its form and structure was seriously flawed” and was exceptionally bad even by the standard of similar bailouts at the time. It “amounted to a gratuitous transfer of money”.

But the (then prevailing) perception that the major benefits went to Absa shareholders was incorrect; the beneficiaries were actually Sanlam’s policy holders and pension fund beneficiaries as well as minority shareholders in Bankorp. Absa, by contrast, had paid fair value for any benefit it later derived when it bought Bankorp.

The Reserve Bank acted outside the law and so restitution would be possible in principle, but “may well be difficult and extremely costly to achieve through litigation” in part because it would be so hard to determine who profited and to what extent.

Ciex report and Project Spear,

December 1999

By UK-based private investigators Ciex, headed by former British intelligence officer Michael Oatley.

Ciex approached the government (in 1997) with the suggestion that apartheid-era plunder could be recovered, and was then commissioned and paid to investigate.

Finding: In a leaked description of its work, Ciex lays out a strategy to raise billions for the government, from which it would take a 10% commission. It says that R3.2‑billion can be recovered from Absa by forcing it into “volunteering” the repayment. It also says that R10‑billion should be claimed from Absa and its shareholders (it is not clear whether this amount includes the R3.2‑billion or is in addition to it) and that another R3.8‑billion can be claimed from Sanlam, on the basis of the enrichment it had enjoyed.

Ciex claims that it fed information to the Heath investigation and had presented a foolproof strategy of overt political pressure and covert machinations to achieve restitution – with no risk to the economy. “If Absa ‘volunteers’ repayment, in an agreed schedule [that] is evidently consistent with the bank’s ability to pay, there can be no question of risk to the bank itself and the whole (entirely spurious) idea of systemic risk also falls away,” Ciex said. It also said that Absa had already “earmarked” money to repay the state.

Special Investigating Unit decision,

November 1999

By the specialist unit tasked with digging up corruption, then headed by Judge Willem Heath. The unit was tasked with the investigation after a preliminary report by Ciex.

Finding: Towards the end of 1999 Heath announced that his unit had dropped its investigation into the Bankorp lifeboat. He said discussions with various banks foreign and local had persuaded the unit that moving forward with legal claims posed a serious risk of depositors making a run on banks generally and not only withdrawing their cash from Absa, so destabilising the banking system to everyone’s detriment.

He later said that charges should have been brought against the Reserve Bank, Absa and Sanlam for their roles in the matter. – Phillip de Wet