The census shows a recent increase in the number of births in all population groups

With R323.6-billion hanging in the balance, an oversight body for Statistics South Africa on Thursday moved to defend the results of Census 2011 from two rebel demographers who say the findings are questionable and should have been more carefully scrutinised before being released this week.

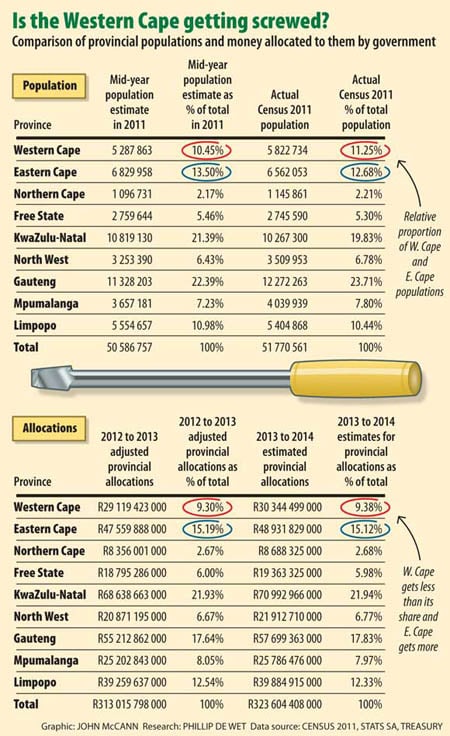

At stake is the division of tax money among the provinces. There is the prospect that hundreds of millions of rands could be added to the budgets of Gauteng and the Western Cape, among others, and subtracted from the likes of the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal over the coming years.

Although the census seeks to be a complete count of individuals, an evaluation of its completeness found that 14.6% of South Africans were not interviewed by enumerators in October 2011. That means data were captured for 44.2-million of an estimated total population of 51.8-million. Where the missing 7558501 live and what exactly their economic and social circumstances are could mean the addition or subtraction of hundreds of millions of rands for individual provinces.

Statistics South Africa says the census conformed to the strictest international standards and is the best reflection of reality available, even though it contradicts other surveys and estimates and shows strange anomalies in, for instance, the rate at which South Africans are having babies. But not everyone agrees.

"We have concerns," said Tom Moultrie, a demographer at the University of Cape Town (UCT). "The age distribution [reported in the census] means that, after a long decline in the birth rate, people started having a lot more babies in the past four years and that's across all the groups, including the white population, where you wouldn't expect that.

"We've also been unable to reconcile these results with [the 2001 census] and there are evident errors in things like the country of birth for foreigners."

What is wrong with the numbers? "We can't answer that question – we haven't had enough time to analyse the data," said Rob Dorrington, who is also a demographer and actuary at UCT. "It will take a good few weeks, a proper interrogation, to decide what is real and what isn't. What we can say now is that it doesn't hang together."

Dissent

Moultrie and Dorrington were part of a group of 12 experts contracted to advise Statistics South Africa on the census. The group included retired census and statistics experts from the United Nations, Australia and the United States, as well as some highly respected locals.

The two Capetonians were the only ones to dissent, Statistics South Africa says. Although Dorrington and Moultrie called for the release of the census results to be delayed for further study, the others were willing to sign off on their accuracy.

But the two academics are highly regarded. Among the local actuaries and demographers approached by the Mail & Guardian this week – none of whom was willing to venture an opinion on the matter yet owing to a lack of time to evaluate and a lack of access to the data – several said an opinion from Dorrington and Moultrie should not be taken lightly. "I'm definitely not going to stand up in a public forum and say Rob and Tom are wrong," said one actuary, who works for a major consulting firm. "They are the experts in this field, the ones we would normally go to for an opinion."

When asked for an opinion on the census data, the Actuarial Society of South Africa referred the M&G to Dorrington.

Statistics South Africa considered the two men's opinion – now known as the Moultrie report – and its call for delay and re-evaluation. On Monday October 22, after three days of sometimes intensely technical debate, the chairperson of the statistics council, Howard Gabriels, went around the room and asked each member individually: "Do you have a reason to recommend we should delay the publication of the results?"

Not a single member said yes, Gabriels said. "Everyone agreed they were comfortable with releasing the report. The council members could form a minority view and we didn't even have that. It was unanimous."

Population distribution

This decision reshaped South Africa in terms of population distribution. With its finding of much more rapid urbanisation and much higher migration than had been anticipated, the census results are, at times, very different from SA's 2011 mid-year population estimates. Until this week they formed the basis of most government decisions.

In Gauteng, there are 94 4060 more people than the mid-year estimates projected. The Western Cape has 53 4871 more people and even the third-smallest province, Mpumalanga, has 382 758 more people, if the results are compared. But in KwaZulu-Natal the census found 551 830 fewer individuals than anticipated.

The size and composition of the population of each province is by far the most important factor used to determine how much money each is allocated. And with results that Statistics South Africa itself says are startling in some regards, the census numbers imply the need for a substantial rebalancing of the books.

In the Western Cape the final allocation of national funds this year would have amounted to R5 507 per person, according to the mid-year estimates of the population. With the money holding steady while the census shows a larger population, that drops to R5 001 per person.

Gauteng has just a hair less than R375 less per person than it expected, whereas KwaZulu-Natal has roughly the same amount more per person.

The treasury, which somewhat controversially got sight of the census results before their general release, has promised to announce forward estimates of provincial spending over the medium-term budget cycle at the end of November.

Population shifts

With provincial budgets for the coming years already roughly drafted and some projects committed to, it is not clear exactly how the treasury will manage the evident population shifts.

But that was a problem for politicians, not statisticians, said statistician general Pali Lehohla.

Although he was surprised by some of the census findings, he said there was no scientific basis to question the census methodology or outcome and where there were flaws in previous estimates, he was responsible for that.

"The mid-year estimates are estimates based on assumptions and all demographers apply their own assumptions," he said. "A definitive arbiter of count is the census and not the model."

Gabriels, who officially commended Lehohla and his department for their work and signed off on the results, said some anomalies also gave him reason to pause – and were cause for introspection among the many professional forecasters who had not predicted them accurately, as well as the department of home affairs.

"Some of the questions we need to ask are whether there are not more younger people migrating to South Africa from other African countries, for example. We need to relook at the impact of the Aids epidemic and the introduction of mother-to-child [antiretroviral treatment] …

"You have to appreciate that although our administrative data on civil registrations for births and deaths have improved, they are still not perfect."

Both Lehohla and Gabriels emphatically dismissed charges that the release of the census data was rushed and chaotic, possibly to the detriment of the country.

"We are obviously very proud that we were able to release the results within 12 months," said Gabriels. "There was no external pressure that caused that, just good work."

How the cake is cut

The provinces receive a mix of conditional grants and specific allocations from the national treasury, but the bulk of their revenue is from an equitable share, a complex formula used to divvy up the provinical allocation – R313-billion this year.

Only 16% of the allocation to each province is determined directly by the size of its population, but calculations involving provincial needs for education, health and their comparative levels of poverty all rely, in essence, on a head count. "Therefore, 94% of the equitable share is influenced by population movements and the characteristics of provincial populations," the treasury said in its budget review last year.

The formula is redistributive to ensure that the well-off provinces in effect subsidise the others. In the current year and in the projections for next year, KwaZulu-Natal gets the biggest part of the total amount by a large margin.