Graeme Williams uses colour to evoke his sense of the city

In 2000, photographer Graeme Williams published a monograph titled The Inner City, mostly featuring photographs taken in Johannesburg between 1996 and 1998. Except for suburb names and dates, the black-and-white photographs are not captioned, lending them a magical muted quality through which to view a transient city struggling to come to terms with its present.

Even when framed together, black and white people hardly interacted in these photographs, separated as they were by glass walls, a seeming invisibility, or a symbolic presence (such as a black man carrying a painting of a white nude into his new Joubert Park flat).

“Even though those pics are hard and South Africa is moving away from a whites-only place to a mixed one, even though they are in your face in a way, there’s a sense of how South Africa is shifting from that Nineties phase,” he says of them. “There’s an idea of trying to hold on to that mixed-race place and how the country would be.”

Williams, who photographed South Africa’s transition for Reuters between 1989 and 1994, has since trained his eye on various aspects of South Africa’s democracy.

“[The year] 1994 was a real break. Apartheid governed almost everything one did photographically and most forms of creativity. Apartheid was the starting point and from there you found a way to whatever you were [saying]. So when Mandela became president, that black cloud evaporated, in a personal sense, but it also took away the starting point.”

Williams says he began consciously to move away from conflict and news photography during a close brush with Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB) members during the Bophuthatswana uprisings that sought to remove the homeland’s figurehead Lucas Mangope.

“You have to believe that you’re not going to get hurt or die. It was only at that Mmabatho thing, which was in 1994, where I photographed a middle-aged AWB man shooting a woman running in between two houses,” he recalls.

“The AWB man saw me and then they came for us and then they just beat me up. The one put a shotgun in my mouth. And luckily an older AWB guy came past and said, ‘Moenie hulle skiet, donder hulle. [Don’t shoot them, beat them.]’ So they just beat us up. “But it was a strange thing. There was a sense that I had just shifted and thought, ‘ah, ja, actually I can [die]’.”

One of his fascinations has not only been the change unfolding but also often its velocity. His return to the subject of the city is particularly noteworthy for both how Williams approached this further recording of the passage of time and the results it yields.

“I thought, if I can feel a feeling and if I’m able to communicate that feeling, that’s enough for me. That was my new starting point. I had no idea whether I could or couldn’t, whether I was successful or not successful.”

A City Refracted, which bagged Williams the Ernest Cole book prize in 2013, is a self-conscious, furtive return to the city to look into its often inaccessible innards.

“So this was more about an isolation within myself and with my perceived sense about people living in the city,” he says.

Williams mentions that he shot the photographs in Hillbrow over three years, trailed by three bodyguards, highlighting this sense of alienation.

“I could have shot it starkly, but I didn’t want to walk in there and shoot it critically. I’m an outsider in the city, in a way. The fact that I have to have three bodyguards to keep my camera means I can’t blend in. I wanted to keep myself as a visitor.”

Williams says his modus operandi was to fetch his three bodyguards and “jol around the city for four or five hours at a time”.

There is often a tension to his subjects, be they going about their business or looking curiously at the photographer. There are also moments of unsettling voyeurism: a nude man washing from a plastic tub in a rubble-strewn corner of an emptied warehouse, naked sex workers uncomfortably averting their eyes from the camera’s gaze, and living spaces devoid of people. “[I was aware] that I would be bringing myself and my prejudices and all the bits of me too, because that’s what one does as a photographer. But I was very clear that I wasn’t going in there as a critical observer.”

Williams says he began moving away from black-and-white photography in the early 2000s. “Colour, for me, is just a tool to communicate another feeling. Black-and-white [photography] was fine, but for me it represented life under apartheid and I wanted to move away from that, but not photograph in colour for colour’s sake. I wanted to move from that and use elements of the colour to almost separate out or to enhance some feeling.”

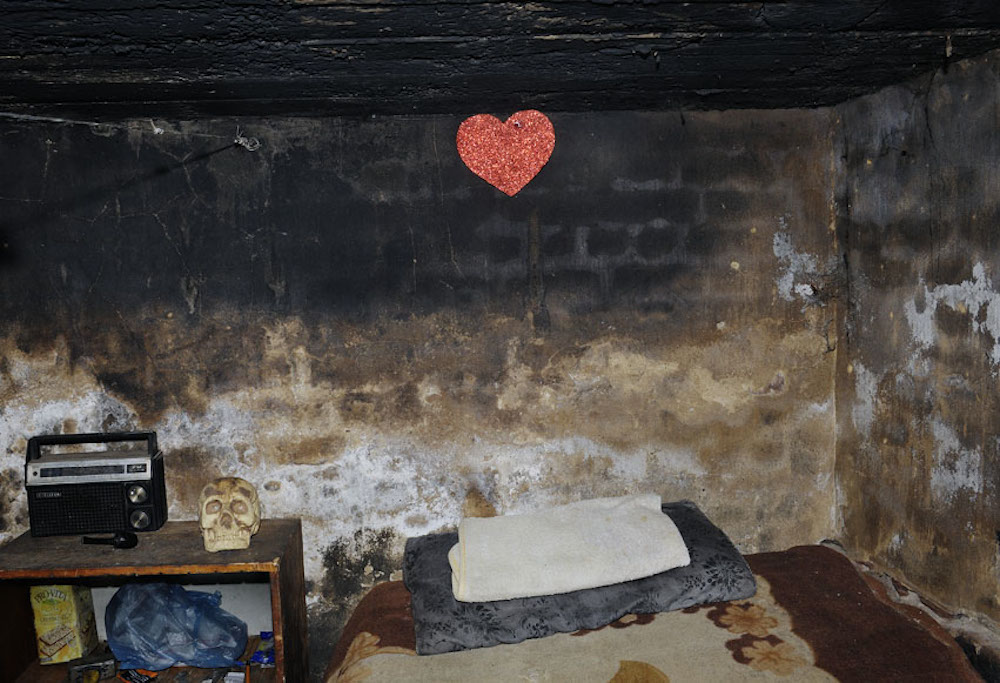

In the collection, Painting over the Present, Williams focused on the interiors and exteriors of poor people’s homes. He used colour as a trick – to detract from the starkness of the surroundings and to utilise it to highlight the humanity of those who dwelt within. It was almost as if the colour was their stand-in, because the inhabitants were hardly ever photographed.

There are similarities in approach here too, although one is never too far away from the haunting feeling that the many photographs of the condemned buildings evoke.

“Even though there might be harshness, I wanted to find a sense of beauty within that. Because, for the people living there, in order to live there, they must find some sense of beauty. Even if it’s a kid’s doll on a table, it doesn’t matter. It’s human nature.”

But much of the beauty in this work is in the photographer’s technique rather than in the interiors and their blemishes.

Williams’s eye for detail, the variations in shutter speed and colour saturation make this collection a varied and lyrical one. Human limbs in motion are juxtaposed with silhouettes of tree branches, the perspective shifted by imposing granite edifices in the background. Green, vine-like shrubbery emerges against algae-covered, damp walls. People are dressed in slivers of light, and Christmas trees are backgrounded by cracked walls and fastened to security gates like leashed dogs. More than anything, this is the visual disorientation of the photographer lived out vicariously through the subject.

It is the fact that Williams does not shy away from this that gives the work honesty and, misgivings aside, makes it compelling to the eye.

In The Inner City, Williams touched on the tension between black and white bodies as white flight was hitting the city. With A City Refracted, he trains his eye on the private spaces of the poor who came to inhabit it. The result of this narrow focus is that he turns a blind eye to the further refraction of the city in the form of gentrification and new enclaves of the rich.

A City Refracted is on at the Wits Arts Museum in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, until January 2016.