It is a simple fact: if schooling in Africa was a commercial enterprise, it would have been closed down because of low output and low levels of efficiency. Equally, if children could vote in elections, schools would have been closed by popular acclaim for largely failing to deliver on their promises.

I want to argue in this three-article series that schooling as currently conceived is an inappropriate and highly inefficient way of replicating the elite, because it sacrifices most children. Equally, it cannot be the basis for growing an educated, enterprising society. I will look at why this is the case and what can be done about it by exploring how schooling should at least be reformed.

The vast majority of schools in rural areas and townships in most African countries are failing. A glance at some statistics should make the point. In most sub-Saharan Africa countries less than 50% of children who enter school complete the primary cycle and less than 25% matriculate. Most of these children leave school before they gain sustainable literacy and numeracy skills.

Worse, in a number of countries, such as Malawi, nearly 25% of children drop out even before they complete grade one. In addition, a Sussex University research project found that a large number of children who manage to stay in school are at risk of permanently dropping out because they are overage; dropped out and came back; are regularly absent; or only turn up for registration or selected lessons. Many more struggle to understand lessons because of a lack of facility in the language of teaching and learning.

This sets the scene for a relatively small percentage of pupils to complete schooling successfully and matriculate at grade 12. Even in the expensive South African schooling system only about 30% of children manage to matriculate. In other words, 70% leave school before completing their schooling, or fail the final exam and so leave with nothing to show for 12 years' work.

These statistics hide the fact that a much higher percentage of middle-class pupils successfully matriculate in these countries than do the children of the urban and rural poor. What this indicates is that in some systems, such as Malawi's, few children who do not come from the educated elite complete schooling and even fewer complete it successfully.

Schools are not fulfilling their most basic task

Again, if this was any other enterprise, with such a low level of internal efficiency and rate of return it would have been substantially reconsidered and reformed. Schools are not fulfilling their most basic task — to create an educated citizenry as the basis for economic and human development. They even fail in many countries to socialise children — many schools are dangerous and sites of violence, harassment and worse.

If we remember that educating young people is critical for the future health, growth and development of any society, it is amazing that schooling has been allowed to fester in most of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

However, the situation is even worse than this. It is not just that few children complete school successfully and so are not able to live their dream of a formal sector job, but this cruel and wasteful system leaves psychological scars related to early failure in a child's life.

We do not know what impact this has on that child's later life. But we can assume that, in societies where more than half of all children experience failure before their 11th birthday, it has a long-term impact on their confidence and self-esteem, their dreams and future life choices.

There is a growing theory that this, combined with political upheavals, leads to many such children being traumatised. The psychological pain is likely to have a negative impact on national economic growth rates and general national psyche and wellbeing. It is certainly going to impact on our ability to make best use of the so-called demographic dividend that Africa is meant to be benefiting from in the near future, when there are more working-age people in the population than children and old people.

And it survives?

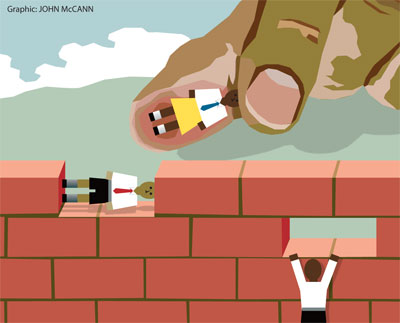

What is intriguing is how this system has been able to survive. Why do the 70% to 90% of children who do not succeed in this game go on playing generation after generation? The reason seems to be that, although schooling systems replicate the elite, they appear to offer all children the opportunity to move out of poverty by offering places at the high table to a relatively few academically gifted children who come from outside the elite. So, many pupils from poor backgrounds attend school regularly and work hard in the hope of escaping poverty.

By playing the game they help to legitimise this apparently fair meritocratic process and finish school believing that they failed through some fault of their own and not because of the innate weighting of the system against them. It is hard not to see these pupils — the vast majority of children in most African countries — as collateral damage in this "fixed" game.

But each generation plays this game, because it is the only game available and there is that chance each child cherishes: they might be the lucky one who gets to university.

It is not just children and their parents who endorse the status quo. The education literature focuses on trying to improve the present system: more resources for schools, better textbooks or teachers, improved training for school managers and so on.

A ladder out of poverty

The implicit starting point is that schools are here to stay and this is the only way to prepare children for life and employment while providing the one legitimate ladder out of poverty. Rarely is the institution of schooling itself questioned in any fundamental way.

So where has all this gone wrong? First, we make a mistake in equating schooling with education — we tend to conflate the two. This is fatal. Schooling in most African countries is a mechanical, factory-era child-containment process at worst. At best schooling is often a process whereby a tired, disillusioned teacher dictates notes to serried ranks of children who are rarely invited to engage with the contents of the lesson and lack the books or internet access to explore further for themselves.

Furthermore, almost all schools in Africa fail to value indigenous know-ledge or any other prior learning with which children arrive at school. Often the knowledge that is taught is foreign to the children, cannot be used in their daily lives and is all too often presented in an exogenous language, such as English, which the children struggle to access.

I am not arguing that schooling is unimportant, but rather that, as the next two articles in this series will suggest, why and how it needs reimagining and reforming.

Education development specialist Dr Martin Prew is a visiting fellow at the University of the Witwatersrand's school of education. This is the first in his three-part series on reimagining schooling