The Johannesburg home procured for Jacob Zuma shortly after he was ousted from government in 2005 has amassed an unpaid bill of nearly R900 000 for water, electricity and other charges, according to documents seen by the Mail & Guardian.

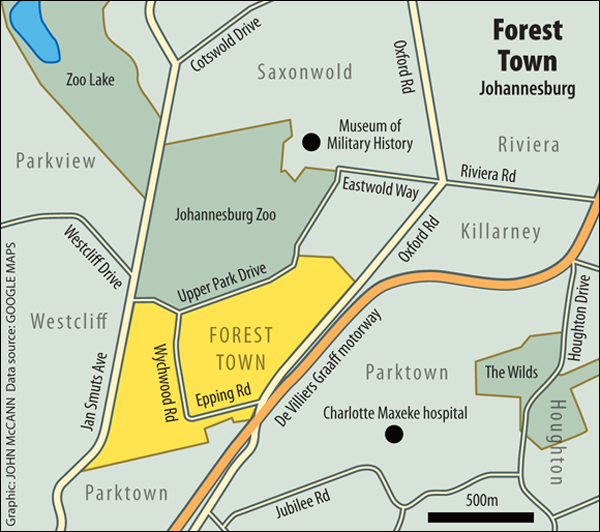

But the City of Johannesburg this week said the municipal account holder for the property – in Epping Road, Forest Town – did not, in fact, owe it anything more than R12 822.15 for rates and taxes in October, and that this amount was payable only in November.

And in yet a further complication, the company that would be liable for the unpaid bill – if any money really is owing – no longer exists, and the last director responsible for it (now a member of Parliament) is under the impression that Zuma or his family now owns the house, something that is not reflected in official records.

Which leaves a house valued at just shy of R5-million without a clear owner, and questions around a seemingly large (but officially nonexistent) municipal services bill.

Earlier this week, it appeared that neither Zuma and his family, nor the official owner, Hola Recruitment and Selection Services, nor that company's last director, Sizani Dubazana, had made any recent payments to the city for water and electricity.

But, responding to detailed questions with a short statement on Wednesday, the city said the account for the nondescript multistorey residence was, in fact, fully paid up.

"We confirm that the account has been investigated and it is not in arrears," said city manager Trevor Fowler in a written response. "All processes were followed by city administration."

Confidentiality

Citing customer confidentiality, the city said it could not answer any other questions. But it added that "a public representative is not entitled to special treatment and none was provided".

In response to subsequent questioning, the city said the account had been settled "a long time ago, a long time before your inquiry", but would not say when it had been settled or explain the discrepancy between its statement and documents issued by its accounts department.

Documents relating to the account show that the outstanding balance due to the city had reached R350 000 in early 2010, had breached R550 000 by mid-2011, and stood at R750 000 a year ago. And although the city said it had followed its own procedures – which would normally entail rapidly disconnecting the electricity to a property with such outstanding accounts – residents of the suburb said they had never noticed it.

In early August, a notice, seen by the M&G, shows the outstanding municipal services account on the home was R855 383.16, and the city was threatening action.

In a standard pre-termination letter, the City of Johannesburg warned that failure to pay the amount within 14 days could lead to "discontinuation or restriction of services" as well as the possibility of "legal action being instituted against yourself without any notice".

The city would not confirm whether any such action had ever been instituted.

Detailed bills show that, thanks to a 2008 valuation of R4.95-million, the property rates come in at about R2000, and water usage and sewerage charges add about R5 000 a month to the total. As is the case in most households, electricity usage is recorded as fluctuating considerably, but invariably makes up the largest portion of the bill.

Until this week, interest on the outstanding total was a growing feature of the monthly bills, heading towards R4000 a year. It is not clear whether the principal amount owing and the interest due on it have been settled or written off by the city, or whether the Zuma family has been a victim of Johannesburg's billing crisis, which has resulted in bills massively inflated in error.

Allegations

The house continues to be used by the Zuma family. The president himself is reportedly a regular visitor, but divides most of his time among official residences in Pretoria and Cape Town and his homestead in Nkandla, KwaZulu-Natal.

Neighbours say that Zuma does not stay for long, but visits almost every week. His visits are easy to notice, they say, thanks to the size of the presidential motorcade.

Zuma has previously failed to pay utility bills on a different property in Johannesburg, but appears to have no real legal liability in the case of the Forest Town house. Instead, such liability would have fallen to MP Sizani Dubazana, one of the benefactors who came to Zuma's rescue when he lost his position in the Mbeki administration in 2005 in the face of corruption allegations against him.

Dubazana bought the property through Hola, of which she was the sole active director, just days after president Thabo Mbeki fired Zuma, which meant that Zuma lost the right to government housing. Zuma quickly moved in.

In 2010, the M&G reported that state institutions had bent over backwards to fund Dubazana at the time of the purchase of the property and that this money may have helped support Zuma. She denied the allegations.

Dubazana, who was elected to Parliament in 2009, has never disclosed the terms under which Zuma gained the use of the property. But regardless of whether he did so under a formal contract, the City of Johannesburg would not, under normal circumstances, turn to him for payment.

Legal existence

"The law says both owners and tenants are jointly and severally liable for consumption charges," said Chantelle Gladwin, a partner at Schindlers Attorneys in Johannesburg, who deals with municipal rates and taxes issues and has studied liability for such accounts. "Hypothetically, you can hold a tenant liable."

In reality, however, the city almost always seeks payment from the property owner, even if the owner is not registered as the municipal account holder.

The Forest Town house is owned by Hola, and the municipal account is also in the name of the company. The result is that both the company and Dubazana personally would normally be held liable for the outstanding amount, with no attempt by the city to approach those actually in occupation formally.

Except that the company no longer exists. According to registration records, Hola has been deregistered, which in effect means it no longer has any legal existence. Reached by phone in Cape Town this week, Dubazana confirmed that the company was no longer active, and dis-avowed responsibility for the Forest Town property, but did confirm that the city had previously sought to recover outstanding rates and taxes.

As far as she knew, Dubazana said, the property had been sold. She could not explain why deeds office records still reflected Hola as the owner.

"It should have been changed. The company did sell the property to the trust." In 2011, various sources on both side of the transaction said that the house was in the process of being sold to a trust linked to the Zuma family. But a search of deeds office records this week turned up no sign of any request to transfer ownership, neither current nor dating from 2011. Dubazana also said she had received calls from the city of Johannesburg seeking payment on rates and taxes as far back as 2010, but those calls stopped coming "quite far back", and she did not know how the matter had been resolved.

Disconnection

The typical resolution, as experienced by many Johannesburg residents in recent years, would start with electricity to the property being turned off, followed by a quick payment. It is a tactic that rarely fails.

"If you turn off the electricity the tenant is affected, and the tenant will pay," said Gladwin. "If the tenant leaves, the owner will pay, or he won't be able to get electricity and water to the new tenant."

And if the owner tries to sell the property, a rates-clearance certificate is required. One way or the other, the city invariably gets its money.

Unless the same tenant stays on the property, as is the case with the Zuma family in Forest Town, and the property remains owned by the same owner, as is technically the case in Hola's ownership of the house, and the city never turns off the electricity.

Why would there be no disconnection? Not because of the prominence or political connections of an occupant or owner, the City of Johannesburg emphasised several times this week. "All customers are the same," City spokesperson Kgamanyane Maphologela said on initial inquiry, emphasising that not even ministers should expect special treatment.

Presidential spokesperson Mac Maharaj could not immediately answer questions on the various mysteries this week, but said they would be referred to Zuma's lawyers.

House of the rising Zuma

The Forest Town house that now has a municipal account that is nearly R900 000 in arrears shot to prominence shortly after Jacob Zuma moved in – the Scorpions raided the house in August 2005 while investigating corruption allegations.

Questions about the ownership of the house, and how Zuma came to live in it, followed, but it would take nearly five years for a fuller picture to emerge.

In March 2010 the Mail & Guardian reported that Sizani Dubazana, then going by the surname Dlamini-Dubazana, had received more than R8-million in loans from a KwaZulu-Natal development fund, part of which may have helped to fund the R3.6-million purchase price of the house.

Dubazana denied this and records show that the full price was covered by a bond from Absa.

Dubazana, acting on behalf of Hola Recruitment and Selection Services, signed an offer to purchase the house, where Zuma would come to live eight days after he was dramatically ousted from his position as deputy president.

Over the following years, Zuma used the house to meet ANC officials, lawyers, whistleblowers, journalists and pop stars. The house made headlines several times, after:

- The dramatic early morning raid by the Scorpions in August 2005, which included simultaneous searches of a number of other properties, including Zuma’s Nkandla homestead;

- Zuma was charged with rape in December 2005 for a sexual encounter in the house with a woman many decades his junior; and

- The detention in February 2010 of two M&G staffers who were photographing it.

In 2011 Dubazana’s lawyer, Brian Clayton, said an entity linked to Zuma had bought the house, but deeds office records still reflected Hola as the owner.

At the time Clayton also said the Zuma family had been making bond payments on the house, as well as paying property rates and taxes.

A matter of utility bills

In December 2011 the presidency issued a short statement in which President Jacob Zuma expressed regret about "unpaid bills and utility bills" and also promised to settle an outstanding bill for services, including electricity and water.

That followed a report in the Star that Zuma owed R120 000 for services to two flats he owned in Berea, Johannesburg, in a building that had apparently been hijacked, then reclaimed by flat owners, then had its services disconnected by the city because of R1.8-million in outstanding rates and taxes.

Zuma said he had not used the flats for several years and the property was being administered by an agent.

Though Zuma was legally liable for the payment of levies that would cover his portion of the building's municipal account, it had apparently been agreed that tenants would pay the levies directly.