Tebogo Dolamo: 'In 90% of my engagements I'm the only black guy in the room.'

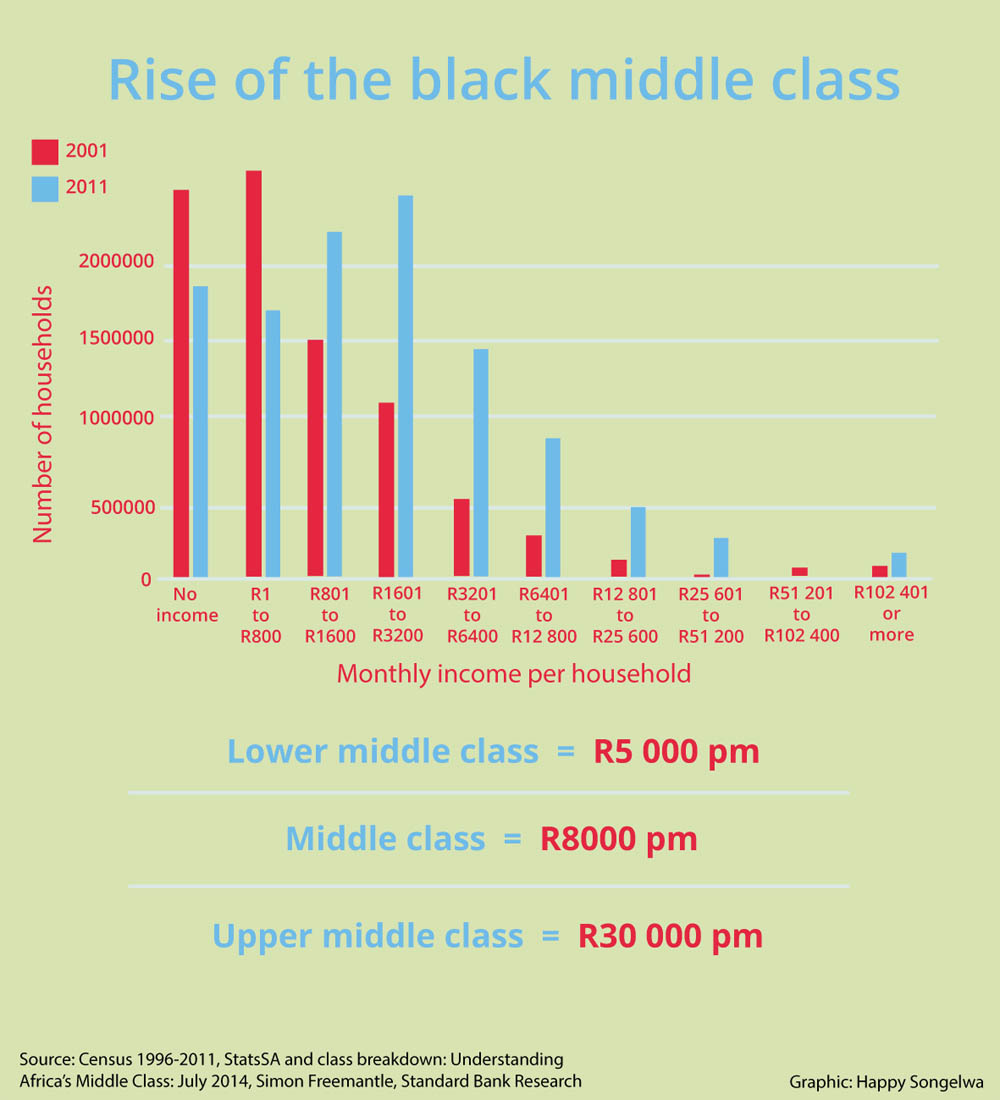

While poverty remains the reality for most black South Africans by far, economists say those numbers are going down, and the black middle class is on the rise.

Tebogo Dolamo

IT Operations Manager

“I look at my other non-black peers and there is no difference. So why classify people and box them up in racial segments?” objects Tebogo Dolamo when I pose the question to him about the black middle class.

“I think it’s silly that when 25% of the population is unemployed and they say if you earn more than R8 000, one is classified as a middle class. How do you get to such a figure?”

I meet the smartly dressed Dolamo on a Thursday morning at the luxurious Palazzo Towers offices at Monte Casino, where the 38-year-old oversees IT for 14 casinos.

His slick corner office in Fourways is a long way from Soweto where he was raised.

“In 90% of my engagements I’m the only black guy in a room,” he says. “But I could not have chosen a better place to grow up. It made me tougher. I can survive anywhere in the world based on my upbringing.”

Dolamo’s mother was a matron nurse and his father was a computer operator for an insurance company. His primary education began in the township, but he matriculated from a private school and went to the University of the Witwatersrand to study corporate finance and business administration.

Today he is married, has three kids, two properties and an exquisite German car.

So life is good. But he has even bigger plans. He’s on an executive development course in the hope that he will someday become a chief information officer.

“I wouldn’t still be here after seven years if I wasn’t delivering,” he says. But adds: “Sometimes it is luck, and you capitalise on it.”

Tshepang Makofane

Digital account manager

Tshepang Makofane has a lot on his mind. He’s an Africanist, he tells me, and admires the ideologies of men like Muammar Gaddafi, Thomas Sankara and Julius Malema.

Makofane, who went to a predominately white school from primary school to a university in Pretoria, says he is “first-generation” middle class and doesn’t believe he is part of the “apartheid legacy”.

“I would like to believe I was not affected by it. I’ve never picked up a stone. My parents grew up in a township … and worked hard for me to get to where I am today.”

But the 23-year-old says that being the only black person on stage the day he graduated from university with a degree in information design, and the only black person in the department where he worked, has shaped his thinking.

“I’m from a generation that everything you do, you become the ‘first black’ to do this. I feel like our achievements are compromised. Don’t praise me because I’m the first black to do this, praise me because I’m the best at what I do.”

Makofane shifts from sounding arrogant and ungrateful to appreciative; he’s an idealist who occasionally appears intimidated by his own dreams. Sometimes he comes across as harsh but, as the saying goes, sometimes the truth hurts.

He says he finds himself, despite his middle-class salary, living pay-cheque-to-pay-cheque.

“If my boss doesn’t pay me at the end of the month, I’m poor again. Even though you are employed or empowered, the black middle class salary is spread in a way that you are looking after many people. So we cannot move on so much. I don’t have a kid, but you will be surprised how many kids I support. How can that be middle class?”

He questions his class status constantly.

“Middle class doesn’t allow me to think,” he says. “Middle class says be careful. Middle class says you are just a number. Middle class doesn’t allow me to dream. Being in the middle is not nice. It’s like having a lukewarm coffee – that’s middle class.”

Banele Sibunzi

Marketing specialist

Ten years ago Banele Sibunzi was living at home with his mother in Dube, Soweto, and using public transportation.

Now, at 33, he works full-time in marketing for one of the county’s biggest telecommunication companies, and owns a townhouse in Ormonde.Considering where he comes from, this means a lot to him.

He was born in a township, where he started his schooling. He subsequently went to better schools and then on to the University of Johannesburg.

Being the last-born, his late father was very strict about his education. It was that tough upbringing that supported him, influencing how he views life, what he eats and how he manages his finances.

For him, “black middle class” means someone who has come from a poor background and has worked their way up the food chain.

“Basically, they are at a point where they have disposable income. They are at a point now that they can afford those things and they look attractive to financial institutions, where they qualify for loans, bonds, cellphone contracts.”

Sibunzi is preparing to marry his fiancée, Julia Olivia Davids.

“We are from different but very similar backgrounds. She is coloured and I’m black. We both come from tough upbringings. We both understand [we have to] work for something in life and [don’t expect to] just get things on a silver platter. I think that’s one thing that has kept us going.”

Sibunzi and Davids find it annoying that people still stare at them wherever they go – at restaurants, shopping malls, or even just driving in their car.

“I think there are still a lot people that, even though apartheid is gone, it’s still in their mind-set,” says Davids. “It’s what they still believe; that if you are an Indian, you are not supposed to be with a black person and if you are coloured you are not supposed to be with a white person.”

Sakhile Mthunywa

Group head of tax

Sakhile Mthunywa collects art. She loves to travel – she says she’s been to most African countries already – and likes to entertain but doesn’t like to cook, unless you count coffee and Coco Pops.

“I was thinking maybe one day in my 60s or 70s I may have a coffee shop,” the tall, slender 33-year-old tells me in her comfortable, three-bedroom flat in Johannesburg’s northern suburbs. “But [only] after I’ve seen the entire world and have collected coffee beans from all over the place.”

As a group head of tax in an insurance office, her work keeps her busy, so much so that she hardly sees her friends.

“That’s why we have decided to save up money each year and go on trips,” she says. “I think the more we work hard and we climb up the ranks at work, the [less we] see each other. So thank God for social networks.”

Mthunywa, whose parents divorced when she was five, lived in different places growing up: with her dad in Diepkloof, her grandfather in Ga-Rankuwa and – for a three-year stretch – in a shack with her mother and brother in Mamelodi.

But now, being a single woman who supports herself, she has found that the men she meets have preconceptions of what she’s all about.

“The dude is like, ‘So you’ve got a car?’ Yes. ‘So you live alone?’ Yes. ‘In your own place?’ Yes. ‘You have a job?’ Yes. ‘You are the head of the department?’ Yes. ‘Oh! You are high maintenance!’ “

Notwithstanding her job, her lifestyle and the numbers that place her firmly in the middle class, she doesn’t relate to the label.

“Honestly when I thought of the middle class, I thought about Desperate Housewives. That’s what I imagined in my head. People in houses with picket fences, who were comfortable. I literally thought that’s them. With their cardigans, their twin sets, and dinner around the table with the swing in the background, that’s what I always thought.”

“Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu,” she says, which, loosely translated, means a person is a person through other people.

“It’s not even un-African, I think it’s un-human. I think it’s going back and putting people in boxes. Who started this anyway? Who started this whole project of which class are you? Can we just treat people the same?” entreats Mthunywa. “Can I walk into a shop in my All Stars and be treated the same as somebody who walks in with their Louis Vuitton bag?”

Lesego Phiri

Marketing specialist

“As a lady, you can’t put your bag on the floor because you are welcoming poverty,” says the flamboyant 29-year-old Lesogo Phiri, grabbing a chair from another table on which to place her Louis Vuitton bag.

She takes off her black Prada sunglasses and calls for a waiter and orders an Apricot Cosmo.

It’s a Saturday morning, the sun is out and we are sitting at the stylish Green Peppercorn restaurant at one of busiest shopping centres in Morningside. Her presence commands attention – Phiri is compact, wearing sea-blue heels and ripped denim jeans – and people can’t help but stare.

Over breakfast she tells me that, as a marketing specialist for a motor finance company, she has driven the latest and greatest cars, from Range Rovers to Jaguars. She currently drives around in a white convertible BMW Z4 .

She likes the finer things in life, and she’s not apologetic about it.

“So we – my sister, cousin and me – try every month to go on a spa date, just the three of us. Get there at lunchtime and have a bit of lunch. Then we do our facials, massage, pedicure, while having a bottle of bubbly.”

She doesn’t believe in the fake-it-until-you-make-it notion of the black middle class getting themselves into debt all the time. She says they are people who have overcome obstacles to get to where they are now. “It doesn’t matter how much they earn, they are still working hard to get more.”

Despite climbing the corporate ladder, Phiri does not aspire to become chief executive. She wants to progress in her career but she fantasises about getting married, having a family. But she doesn’t believe in 50-50. “A man must provide 80% and me 20%,” she says. “He is head of the house but it’s my responsibility to make that house a home – and that’s where my 20% comes in.”

Luyanda Mafungo

Client relationship manager

From a young age, Luyanda Mafungo was cautious about what it meant to be black. “There’s something about this skin of mine that makes people angry. Sometimes it makes people cry, sometimes it makes people happy, but there is something about my skin.”

The 36-year-old grew up in an educated family; her grandparents were teachers, her father was the country’s first black pathologist and her mother was a nurse who later pursued law.

She grew up all over South Africa and went to a boarding school for girls in Grahamstown, where her schoolmates were surprised that she was reading Malcolm X. She remembers when her father came home with the Roots series by Alex Haley. “At that time I didn’t understand,” she says. “The only think I knew was that there was something about being black that needed to be celebrated.”

As for the black middle class? She says she sees two categories there: functional and dysfunctional.

“The functional black middle class is the black middle class that has an awareness of a child’s basic right to education. They are cautious about their part in society. They are very active and participatory in societal initiatives that promote health education. They are well informed. They are very supportive of each other. They are very progressive thinkers. They want to take this country forward.”

When she gets to the dysfunctional black middle class, her encouraging tone drops and her face changes. “They will not think further than the next day. Non-progressive. They accept the status quo as it is. They are scared to challenge, scared to innovate. They are not strong contenders in the economic landscape. They are fear-driven.”

While she currently works as a client relationship manager, she is also writing a motivational book and aspires to be a life coach. Still, it is the past and the colour of the skin that she considers quite a lot.

“We need to rise up to the fact that what has happened has happened, but we need to allow our Creator to excel himself through our creativity, through our entrepreneurial flair, through our contribution.”

Oupa Nkosi, a photographer for the Mail & Guardian, writes for the publication occasionally.